The analysis “Algeria’s and Libya’s Petroleum Fiscal Frameworks,” has been published by the Oil and Gas Council, the leading network of energy executives in the world. This analysis

is related to Africa Assembly 2018, which is the largest African O&G

finance and investment event. The Oil and Gas Council will organize Africa

Assembly 2018 on June 5-6 in Paris, France.

May 16,

2018

London,

United Kingdom

INTRODUCTION

Algeria

and Libya are two of the world’s most important petroleum-producing countries. According

to BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2017, Algeria owns 12.2 billion

barrels of proven oil reserves (0.7% of the world’s total) and 4.5 trillion

cubic meters of proven natural gas reserves (2.4% of the world’s total, 11th

position in the ranking), while Libya owns 48.4 billion barrels of proven oil

reserves (2.8% of the world’s total, 9th position in the ranking) and

1.5 trillion cubic meters of proven natural gas reserves (0.8% of the world’s

total). However, it’s worth noting that, as of today, Algeria and Libya have still

large swathes of territory completely unexplored for hydrocarbons.

Algeria

with an annual production of 91.3 billion cubic meters is the leading natural

gas producer in Africa, while Libya with 10.1 billion cubic meters is the fourth.

With reference to crude oil production, recent data show that Algeria is

currently producing about 1.5 million barrels per day (in 2007, its production

was close to 2.0 million barrels per day), while Libya, the holder of Africa’s

largest proven crude oil reserves, is currently producing about 1.0 million

barrels per day (in 2007, its production was more than 1.8 million barrels per

day). The main export market for the hydrocarbons of both countries is Europe.

For

both Algeria and Libya, hydrocarbons have long been the backbone of the

economy. In specific, according to the International Monetary Fund (I.M.F.), in

Algeria, hydrocarbons account for about 30% of the G.D.P., 60% of government revenues,

and almost 95% of export earnings. In Libya, because of the ongoing civil war,

it’s difficult to have a reliable evaluation. In any case, in Libya, in 2012, i.e.,

after the demise of Gaddafi’s regime and before the beginning of the Second Libyan

Civil War (2014-present), oil and gas accounted for 60% of the G.D.P., almost

96% of government revenues, and 98% of export earnings.

It’s

clear from the above data that these two countries share a similar economic

structure although Algeria has a more diversified G.D.P. composition than Libya

has. Algeria has a preponderant role as a natural gas exporter, while Libya has

an analogous role in relation to crude oil. What is interesting is that, in

order to improve the development of their respective petroleum (oil and gas)

sector, both countries will need to modify their petroleum fiscal frameworks because

of the changed petroleum fiscal landscape at the global level. Of course,

amending the petroleum fiscal framework is presently secondary in either country

to solving its respective present political challenges.

At

the political level, Algeria is currently facing important challenges primarily

linked to the tough economic conditions (the reduction in oil prices is the

main culprit), the complicated presidential election scheduled for May 2019,

and the terroristic menace originating from Algeria’s neighboring countries.

Despite the increase in the price of oil that has occurred over the last few months,

the Algerian government has little room for maneuver because of its limited

financial resources, and it faces now more difficulties in economically

appeasing the demonstrators currently carrying out strikes across the country as

it had done in the past. In fact, in the past, the country used to avert unrest

by redistributing its oil revenues.

For

Libya, because of the Second Libyan Civil War, the present conditions are much

more complicated. The country is at the mercy of the conflict among rival factions seeking control over the territory

and the oil reserves. Presently, there are two main factions: the first one is the

Government of National Accord, which is supported by the United Nations and

controls the Tripoli area and an area of southwestern territory along the

border with Algeria, and the second one is the Tobruk-led government, which

controls all central and eastern Libya and has the loyalty of the Libyan

National Army under the command of General Khalifa Haftar.

THE

PREMISE: A CHANGING PETROLUEM FISCAL LANDSCAPE

The main problem with the petroleum contracts is linked

to one of their principal characteristics, i.e., their long duration; many

times, three decades is quite a normal duration. And, during these decades, the

economic profitability based on the initial contractual terms may change

consistently. The petroleum business is subject to price cycles linked to several

factors—sometimes real boom-bust cycles. So, the best approach when drafting a petroleum

contract is to provide it with real flexibility capable of withstanding a different

economic landscape. In other words, flexibility that is not based on purely

maintaining the status quo present at the time of the signature (for instance,

thanks to a strict stabilization clause), but that is based on maintaining a

correct equilibrium between the involved parties (for instance, thanks to an

equilibrium or outcome-based clause).

In other words, the goal must be to ‘account for’ in

a fair and equitable manner and not just ‘take into account’ the different

economic conditions. However, this is easier said than done. On top of this, an

additional hurdle is that when drafting a petroleum contract, the involved

actors behaviorally give a lot more attention to the economic conditions

present at the time of the signature. This tendency is the normal trend. The

problem is that the economic conditions present at the time of the signature

might radically change in just few months. For example, in June 2014, the price

of a barrel of oil (Europe Brent crude spot price) was about $115, while in

December 2014, i.e., six months later, the price was $65 (a 43% decline).

At the end of the 1990s and beginning of 2000s, the

price of a barrel of oil sustained an upward trend. Chindia, i.e., China and

India, increased year after year its oil consumption, and the U.S. had still to

begin its fracking operations. So, the governments of oil-producing countries started

to engage in revising the substantial contractual terms that were the

foundations on which the international petroleum companies had based their

decisions to sign the petroleum contracts. As a result, relevant changes

occurred especially when originally the contracts had been signed in times of

low oil prices (for example, in those 15 years between 1985 and 1999).

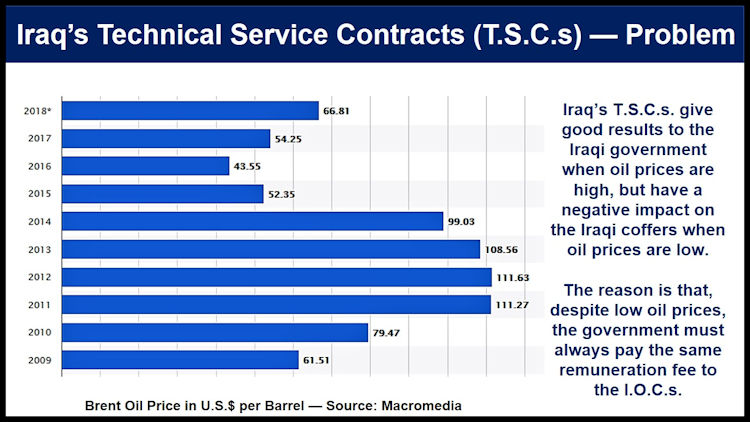

Presently, after the price decline that started in

June 2014, the petroleum fiscal frameworks and the relating contracts of

several countries have been recently incapable of attracting a reasonable

number of international oil companies (I.O.C.s). So, some of these countries

are thinking of amending their fiscal frameworks and contracts—see, for example,

the recent changes in Iraq. However, at the time of this writing, the price of

oil has increased for the past ten months because of politically motivated

production restriction, increased demand, reduced investment in the past years,

and geopolitical tensions (for instance, in Venezuela and Iran).

ALGERIA’S

PETROLEUM FISCAL FRAMEWORK

Algeria became independent from France in 1962, but

some relevant hydrocarbon discoveries had already occurred in the 1950s. In

fact, in 1956 were discovered the Hassi Messaoud and the Hassi R’mel oil fields—still

today, the country’s two largest oil fields. Then, in 1963, Algeria established

Sonatrach, its national petroleum company. At the beginning of its petroleum

operations, Algeria’s petroleum legal regime was based on petroleum concessions,

which were released by the French authorities. Some years later, in 1970,

Algeria began to expropriate some foreign petroleum companies, and, by the end

of the year, all the assets of the non-French petroleum companies present in

Algeria had been nationalized.

Then, the following year, the Algerian government

nationalized a 51% stake in each of the concessions still managed by the French

petroleum companies. At the same time, the government nationalized completely

the gas sector and the oil and gas pipelines companies. The result was that, in

just few years, the petroleum sector was almost completely controlled by the

Algerian government. On top of this, in 1980, also France’s Total was obliged

to exit the market when the government refused to extend the association

agreements with the company. Technically, the petroleum sector was not

completely closed to the I.O.C.s, but the terms were so harsh that the I.O.C.s

were not much interested any longer into investing in Algeria.

After this last change, some problems materialized

quite soon because in those years the oil prices declined and because Sonatrach

did not really have the technological expertise to develop a petroleum sector

that at that time started to have some mature fields requiring top-notch petroleum

skills. Understanding these difficulties, in 1986, Algeria passed a new

hydrocarbon law, Law No. 86-14, which introduced the production sharing

contracts (P.S.C.s) and risk service contracts in Algeria. The idea was to relax

the offered fiscal terms with the specific goal of attracting again the

technologically savvy I.O.C.s to Algeria. The problem was that the offered

conditions were not sufficiently good to lure the I.O.C.s back to Algeria.

However, in 1991, when the Parliament passed some

amendments to Law No. 86-14, Algeria was able to attract one more time the

I.O.C.s back to Algeria. The amendments concerned improved fiscal terms and the

general conditions relating to the investment operations (the possibility of

benefiting from international arbitration was an essential element). This move was

successful because in the 1990s I.O.C.s coming from very different geographic

areas returned to invest in Algeria in partnership with Sonatrach, which

maintained a minimum 51% stake in all the upstream projects.

Then, in April 2005, Algeria introduced Law No.

05-07, whose goal was to modify the oil and gas sector framework. It was

created al Naft, which is the body responsible for the organization of the

licensing rounds and the award of the contracts, and the Hydrocarbon Regulatory

Authority, which is responsible for technical matters. This law reintroduced in

Algeria tax and royalty petroleum agreements (concessions) and blocked with

reference to future agreements the application of both the P.S.C.s and the risk

service contracts. According to this law, the I.O.C.s were supposed to pay a

proportional royalty linked to the location and the production of a field and

to pay income tax based on a sliding scale increasing with the increase in the

hydrocarbons production. It’s worth noting that, despite the enactment of Law

No. 05-07, the P.S.C.s entered by Algeria under Law No. 86-14 were still valid—in

other words, the new law did not act retroactively invalidating those contracts.

In addition, Law No. 05-07 abrogated the necessary

requirement that Sonatrach had a 51% stake in all the upstream projects. However,

this abrogation lasted for just a year because, in July 2006, Order No. 06-10

reintroduced Sonatrach’s mandatory 51% stake. In practice, the risk of the

exploratory phase in Algeria is all on the I.O.C.s, but then, when there is a

commercially viable discovery, Sonatrach must get at least a 51% stake. The

order also introduced retroactive taxation concerning all the P.S.C.s executed

before Law No. 05-07, and it introduced in relation to contracts signed under

Law No. 86-14, a windfall profits tax applied at rates ranging from 5% to 50% according

to the production level when the arithmetic price of oil exceeds $30 a barrel.

Then, in February 2013, Law. 13-01 introduced some

incentives for the development of unconventional oil and gas. According to this

law, the taxation is now based on profit and not on total revenue. At the same

time, with reference to the unconventional resources, this law lowered the tax rates

and permitted a longer exploration phase (11 years for the unconventional

resources versus 7 years for the conventional resources) and longer

operating/production periods (30 years and 40 years for unconventional liquids

and gaseous hydrocarbons, respectively, versus 25 years and 30 years for

conventional liquids and gaseous hydrocarbons, respectively).

As of today, in Algeria exploration and/or

exploitation activities must follow the signature of a tax and royalty

petroleum agreement, i.e., a concession. Al Naft’s selection of a contracting

party is done via a tender procedure, although the Minister for Hydrocarbons

may opt for a direct agreement with a specific contractor. The Algerian state has the right to ownership over discovered or undiscovered

natural resources located on the soil or subsoil of the national territory.

Sonatrach still has have in any agreement a participation stake of at least

51%; a joint operating agreement signed by Sonatrach and its partners (national

or foreigner partners) is attached to the agreement. It’s important to

underline that all the foreign contracting parties to an agreement must

establish an Algerian branch.

With reference to the taxation

concerning petroleum agreements signed under Law No. 05-07, as amended, hydrocarbons

areas are divided among four different zones, i.e., Zone A, Zone B, Zone C, and

Zone D. Taxation is based on four separate components: the surface area tax,

the royalty tax, the petroleum income tax, and the additional profits tax.

However, each zone has a different taxation level. The surface area tax, equal

to the product of the surface of the contractual area and a specific price per

square kilometer, depends primarily on the tax zone and on the type of activity

carried out. The surface area tax is a non-deductible charge from the tax base

for the calculation of other different taxes. This surface area tax is

considered for the determination of the rate that is used for determining the petroleum income tax.

The royalty is a percentage of

the ‘value of production minus transport costs’ calculated on a deposit by

deposit basis. Its value is 5.5% to 20%. The different percentages depend on

the level of production and on the specific zone. No matter what the production

is, unconventional hydrocarbons have all a 5% rate. The royalty is a deductible

charge from the tax base for the calculation of the petroleum income tax and of the additional profits tax.

The petroleum income tax is also determined on a deposit

by deposit basis. Its rate is linked to the profitability of the investment. It

has a minimum rate of 10% to 30% and a maximum rate of 40% to 70% depending on

whether the deposit is conventional, unconventional, or geologically complex. Petroleum

income, determined on a deposit by deposit basis, is defined as the value of

the production minus the following deductions: the royalty, the annual

investment tranches for the development with their uplift values, the annual

investment tranches for research with their uplift values, the abandonment

and/or restoration costs, the training costs, the costs relating to the gas

reinjected into the deposit. The petroleum income tax

is a deductible charge from

the tax base for the calculation of the additional profits tax.

The additional profits tax is applied to the consolidated

profit of all the oil activities carried out by the investors in Algeria. It’s

due by all the entities in an exploration

or production contract, and it is based on the annual profits after the

petroleum income tax. The royalty, the petroleum income tax, the depreciation,

the reserves for abandonment or restoration costs are all deducted for the

calculation of the taxable basis. There are two applicable rates: 30% and 15% (the

latter rate is for profits that are reinvested). According to Law No. 13-01,

for unconventional oil and gas, small deposits, and underexplored areas that

have complex geology and/or that lack infrastructure, each company that is

party to the agreement is subject to a reduced rate set at 19% (instead of the

standard 30%) according to some specific conditions and depreciation rates.

Instead, the contracts signed under Law No. 86-14 have

three different main taxes: the royalty tax, the income tax, and the above-mentioned

windfall tax. With these contracts, royalty is due on the gross income, and

it’s paid by Sonatrach at a rate

of 20%. The royalty rate can be reduced to 16.25% for zone A and 12.5% for zone

B. Moreover, The Ministry of Finance can reduce the royalty rate further to a

limit of 10%. The income tax is fixed at the rate of 38%, it applies to the

profit made by a foreign partner, and it is paid by Sonatrach on its behalf.

According to an analysis by Rystad Energy and the

Boston Consulting Group, Algeria’s government take was 88% between 2009 and

2014. The government take may be defined as the government share of ‘gross

revenues’ minus ‘costs.’ Indeed, this value is very high. It’s true that to

analyze a petroleum contract, the government take parameter might not be a

perfect indicator, but it’s also true that it may well serve as a useful

initial reference point (Johnston 2003), and for this reason it’s used

internationally as the measure for defining the competitiveness of a country’s

petroleum fiscal system. The government take is even more important when oil

prices decline and when the companies reduce their investments as well, because

it’s exactly at that time that countries compete to attract the reduced number

of possible investors.

Algeria is currently planning to amend its

hydrocarbons law to attract investors because the last invitations to tender have

resulted in negative outcomes. For example, in 2014, Algeria was capable of

awarding only 4 blocks out 31 blocks on offer. All this said, it’s also true

that the precarious security environment, especially in the areas far from the

coastline, does not help to attract the I.O.C.s. An auction was planned for the

second part of 2015, but it was canceled because of the negative results of the

previous tenders. These negative results call for a more enticing regulatory

framework (better tax provisions) capable of better balancing the interests of

both Algeria, on the one side, and the I.O.C.s, on the other side.

Algeria needs both technical expertise and

financial resources to explore those two-thirds of territory still today

completely unexplored for oil and gas, and at the same time to start tapping

its shale oil and shale gas resources. Maintaining Sonatrach’s 51% majority

stake in all of Algeria’s hydrocarbons projects is probable is not tenable any

longer; it’s time that the I.O.C.s have a larger role in the projects. Still

today, Sonatrach owns about 80% of all oil and gas production. Similarly, the

present tax law, which was drafted when oil prices were high, might be modified

to better account for a different range of oil prices.

LIBYA’S

PETROLEUM FISCAL FRAMEWORK

Libya’s petroleum development started in 1955 with

the promulgation of Law. No. 25, a.k.a., the Petroleum Law. In the same year,

Libya granted its first concessions—what was immediately interesting was that

the concessions concerned small areas and that there were relinquishment

obligations included. This law has been amended over the course of the

following decades several times, and it’s still today the backbone of the

country’s petroleum sector. Those first concessions gave the I.O.C.s the complete

control over all the petroleum operations.

By the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s,

Libya started requesting tougher fiscal terms from the I.O.C.s. In specific,

Libya wanted to have a larger share of the petroleum revenue, and, in 1970, it

increased its royalties from the concession agreements with the I.O.C.s to a

55% share. Then, in 1972-1973, the concessions were transformed into

participation agreements in which Libya’s National Oil Corporation (N.O.C., the

petroleum state company) was entitled to a 51% stake. And, in 1973, a 51% stake in each of the concessions

whose concessionaries had previously refused to transform their concessions

into participation agreements was nationalized.

In 1974, Libya introduced its first exploration and

production sharing contracts (E.P.S.A.s). In practice, the government decided

to have a petroleum fiscal framework based on production sharing contracts

(P.S.C.s). Until today, Libya has introduced four versions of the E.P.S.A.s.

Today’s contract is the E.P.S.A. IV, which was used for the first time in January

2005 on the occasion of the first licensing round after the lift of the

sanctions against Libya in 2004. The E.P.S.A. IV terms are quite tough, but this

contract was quite successful in 2005 because at that time oil prices were rising,

there were not many interesting acreages on offer across the globe, and Libya’s

coastline is quite close to Europe, which has a large oil-importing market. In

fact, the 2005 E.P.S.A. IV licensing round, which was a sealed-bid round, saw

15 blocks on offer and an average of 7 bids per block.

Since 2005, Libya has held four licensing rounds based

on the E.P.S.A. IV. The first one in January 2005, the second one in October

2006, the third one in December 2006, and the last one in December 2007 (the

latter exclusively for gas fields). In general terms, the first three rounds

were quite successful (on average they had an 87% award rate), while the fourth

one, the gas round, had only a 50% award rate. The reason for the disappointing

result of the fourth round was that at least some of the I.O.C.s were quite

unhappy with the strict terms and operating conditions. In fact, the winning

I.O.C.s had all low production sharing percentages.

In any case, today if an I.O.C. wants to carry out

petroleum operations in Libya, unless it takes over an existing interest, it

must enter an E.P.S.A. IV with N.O.C. In general, if there is the need for

I.O.C.s, the government organizes a bid round. I.O.C.s make their bids, and the

winning company will open a branch office in Libya. The E.P.S.A. IV model provides

for a contractual period of 30 years (5 years for the exploration and 25 years

for the exploitation).

According to the E.P.S.A. IV, the I.O.C.s must bid

the percentage of gross production directly reserved for the N.O.C.—later in

the project, when the cumulative costs will be quite low, this share of gross

production will appear more as a sort of regressive royalty. In case there is a

tie on the gross-production percentage reserved for N.O.C., the signature bonus

will be the tiebreaker. In 2005, the first time that Libya used the E.P.S.A.

IV, the blocks on offer were quite large (on the order of more than 2 million

acres each); large blocks may be a drag on the I.O.C.s because, in such a

situation, companies might have important sunk costs before the discovery of a

commercially exploitable quantity of hydrocarbons.

In addition to the signature bonus, each block on

offer has several production bonuses linked to the cumulative production coming

out of the block. The E.P.S.A. IV requires N.O.C to pay 50% of capital

expenditures (capex) and its share (percentage) of operating expenditures (opex,

this share corresponds to the gross-production percentage reserved for N.O.C.,

i.e., the first (and fundamental) bid parameter. N.O.C. does not directly cover

the exploration costs. These costs are directly expensed by the I.O.C.s, which

could recover them as cost oil.

The I.O.C.s’ cost oil comprises three elements:

1 — 100% of exploration costs

2 — 50% of capex

3 — the ‘%’ of opex corresponding to the ‘%’ of the

I.O.C.s’ gross production

In any calendar year, a specific percentage of

production must be allocated to the I.O.C.s for cost recovery until the cumulative

value of such allocation equals the cumulative petroleum operations

expenditures incurred by the I.O.C.s. Thereafter, any excess of such allocation

to the I.O.C.s (Excess Petroleum) shall be allocated to the I.O.C.s according

to the formula: ‘Base Factor’ multiplied by ‘A Factor’ multiplied by ‘Excess Petroleum.’

The base factor at the indicated levels of the

average total daily production in barrels of crude oil and liquid hydrocarbon

by-product, is defined by a specific table according to which the various

levels of production have a different base factor. In practice, if, for

example, excess oil is 50,000 b/d, the base factor will be for the first 20,000

barrels 0.95, for the second 10,000 barrels 0.80, and for the remaining 20,000

barrels 0.60. If we multiply each tranche of barrels by its corresponding base factor,

sum the results, and then divide the result of the sum by the overall excess

oil, we will get the final base factor. Instead, the A factor is the result of

dividing the I.O.C.s’ cumulative revenues by the relating expenditures (the sum

of both capex and opex). According to the obtained ratio, the I.O.C.s will use

a different A factor as expressed in a specific table. N.O.C. pays the taxes on

behalf of the I.O.C.s.

The overall result of the 2005 E.P.S.A.s was that

the government had a government take on the order of about 88% across all the

blocks. This percentage was very high despite the government participated in

50% of capex and in a percentage of opex corresponding to the percentage value

of its reserved gross production. And, according to an analysis by Rystad

Energy and the Boston Consulting Group, Libya’s government take was 76% between

2009 and 2014. The basic idea is that the contractual terms of the E.P.S.A. IV

are quite harsh. According to these terms, some discoveries, despite being

quite large, may sometimes not be sufficiently large to declare them

commercially viable.

Already before the commencement of the hostilities

against Colonel Gaddafi, in Libya there was the idea of passing a new and more

encompassing hydrocarbon law with specific chapters covering natural gas and enhanced

oil recovery (E.O.R.) projects. Moreover, immediately after the demise of

Colonel Gaddafi’s regime, some of the discussions focused on the structure and

the management of the hydrocarbons industry with specific attention given to

expanding the downstream sector, reforming the subsidies, restructuring N.O.C.,

and amending the upstream contracts. N.O.C.

was thinking of having another bid round as well. However, because of the

ongoing civil war, all this program has been put on the backburner.

The I.O.C.s would like Libya to present an updated

version of the E.P.S.A. with more attractive terms with reference to the

companies’ profitability. At the same time, the companies would like to have

some reforms concerning the way the management committee works, the application

of force majeure, and the training and employment of Libyan nationals. In

specific, the problem with the management committee is that sometimes this body

is incapable of taking decisions because there is no unanimous decision, which

is instead mandatorily requested. If there is this deadlock, the matter at hand

is then passed to the senior management. However, it’s not guaranteed

that a solution will be found also at this level. So, delays may be a regular

occurrence, which has a negative impact on the contractual obligations.

.JPG)