November 6, 2014

Beirut, LEBANON

ABSTRACT — The

Syrian energy industry is currently in complete turmoil as a consequence of the

Syrian Civil War, which started in March 2011. After more than three years and

a half of civil war, Syria is divided between warring parties. This paper

develops an analysis of Syria's energy industry with reference to the "oil"

sector — the natural gas sector is not considered. Despite scarce and

reliable data because of the ongoing war, the first chapter "The Current Condition of the Oil Sector in

Syria" tries to understand the present state of the oil business in

the country. The second chapter "The

Syrian Oil Sector: An Overview" presents a general description of the

oil sector as this was before the war. Finally, the third chapter "Will Syria Be an Oil Transportation Hub in

the Future?" considers whether Syria could one day become a Middle

Eastern transit hub for oil. This last point is quite relevant because in the

last decades many opportunities related to this goal have been missed.

CHAPTER I — The Current Condition

of the Oil Sector in Syria

In

fall 2014 discussions about Syria's oil sector are all focused on the

Islamic State (a.k.a. ISIS or ISIL) occupation of large swaths of eastern Syria

and precisely of some oil-producing governorates. At the time of this writing,

clashes between the Islamic State fighters and Kurdish groups are taking place

in the Syrian town of Kobani, which is located along the border with Turkey.

Kobani, in Aleppo Governorate, is a strategic point for both contenders: For

the Islamic State it is an oil transit route for smuggling oil to Turkey, while

for the Kurds it is the place where to lay a potential pipeline transporting

crude oil from Iraqi Kurdistan.

|

Syrian Civil War — Current Military

Situation

Source: Wikipedia (Nov. 2014) |

Already

in late 2013, the Syrian government had lost control of the country's most

relevant oil fields. In fact, last August, the Islamic State was in control of

six fields in eastern Syria. Some sources affirm that in the Deir ez-Zour area,

the Islamic State manages wells capable of producing 130,000 barrels per day (bbl/d)

of mostly crude oil. In addition to the Kobani battle, currently, there is also

an intense fighting in northeastern Syria, in the Hasakah Governorate, between

the Islamic State and the People's Protection Unitis (Y.P.G.), which is the militant

arm of the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (P.Y.D). Syrian Kurds after the

beginning of the civil war exerted their control over this governorate and the

P.Y.D. declared self-governance in late 2013. Exercising its power over also this

northeastern corner of Syria — where there is the Rumailan crude oil field — would

mean for the Islamic State to control nearly all of the country's oil fields as well as the access road to northern Iraq. Presently, government troops by themselves would be absolutely incapable of retrieving the lost ground in northeastern Syria.

|

| Governorates of Syria — Source: Wikipedia |

Oil

wells permit the terrorist organization an easy access to economic resources,

which are of paramount importance to continue to wage war in Syria and Iraq.

Probably, thanks to oil last June, in Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State was

able to raise as much as $2 million a day. After in September, the United

States and some allies have started conducting airstrikes against the terrorist

group in Syria, the Islamic State should now control between Iraq and Syria approximately

20,000 bbl/d of oil from the 70,000 bbl/d that it managed in August. It is not

clear how much the Islamic State is obtaining from its oil trade. But if it were

able to sell 20,000 bbl/d at $20 a barrel on the black market, it would earn half

million dollars a day. The price for a refined barrel is in the range of $50 to

$60. Most of the Islamic State production is in Iraq and not in Syria.

The

Islamic State does not have the skills required to manage the fields under its occupation

— in the oil business it's "upstream" where the Islamic State has its

most complex challenges. It probably produces only half the fields' regular output

and, given its lack of expertise and know-how it risks seriously damaging in a

permanent manner the mature Syrian oil fields, which need qualified personnel

because they are in the final part of the production curve. But, if on the one

hand, for the Islamic State tapping the resources is not an easy task, on the

other hand, the organization has been quite successful in tapping the smuggling

network in order to sell its oil. Oil exchanges are done in cash through

middlemen with no real bank traceability. Airstrikes are also targeting many Chinese-

and Turkish-makeshift refineries (each is able to process around 200 bbl/d of

crude oil), which are the tools permitting the jihadis to wage their war.

Reports say that the group is selling crude oil and petroleum products

(gasoline, diesel fuel and propane) to black market dealers in Syria, Iraq,

Turkey and Jordan. Some of the dealers are then reselling petroleum products

and crude oil also to the Syrian government.

Oil

resources are showing that the terrorist organizations in Syria are not able to

run like "real states" wide expanses of territory where several

million people live. The economic model of these terrorist organizations, based

on looting crude oil and economic resources, is not sustainable in the long

run. If terrorist organizations act like countries they have to provide basic

government services, which cost money and require a careful management. Absent

a viable economic model, these organizations may become only a sort of failed

state (like Somalia).

One

final economic consideration about the Islamic State: In no viable and realistic

way can the trade of crude oil as wells as refined products on a large scale be

based on truck exports. In fact, Syria before the war used three main pipelines

in order to move oil from eastern Syria to western Syria where there are the

largest cities, the refineries and the export terminals. Moving crude oil and

refined products via trucks means that the business is not sound and has a

scarce sustainability in the long run.

Because

of the conflict, Syria is in short supply of heating oil and fuel oil for its

citizens. At the start of 2013 Iran opened a $3 billion credit with the Central

Bank of Syria to cover oil supplies (crude oil and refined products) — this was

a part of an overall $7 billion credit. According to Reuters, between February

and October 2013, 17 million barrels of crude were shipped to the Baniyas Refinery

through tankers from Iran and Iraq via the Sumed Pipeline (Egypt). In 2012,

both Iraq and Iran had already agreed to ship fuel oil and liquefied petroleum

gas (L.P.G.) to Syria.

In

specific, since the beginning of the coalition’s airstrikes on Sept. 23, oil

prices have skyrocketed in Syria. The airstrikes against the energy

installations are having an impact on the Islamic State but at the same time

they have an impact on the Syrian population, which in the last weeks has seen

important increases in the price of many primary goods (energy and food). And at

the beginning of October, the Syrian government decided to increase the price of

oil products (33 percent increase for gas oil and 17 percent increase for

gasoline) and to permit the private sector to import various oil derivatives,

which the private sector may then resell only to industrial concerns — in

practice after many decades state monopoly was over. These two decisions make

economic sense because currently neither the Islamic State nor Iran are really

able to provide the quantities of energy (both oil and gas) necessary to run a

country like Syria — it seems that the government is buying vessels also from

other countries. And at the same time, the government is not anymore able to

subsidize oil products as it has been doing until recently.

CHAPTER II — The Syrian Oil

Sector: An Overview

1) Organization of the Sector — The

oil and gas sector is under the control of the Ministry of Oil and Gas.

National Law No. 7 of 1953 established that petroleum resources found in the

subsoil and off the Syrian continental shelf belong to the Syrian state. Later,

in 1964, Syria passed Decree 133/22, which limited licenses for exploration and

investment to the Syrian government. Petroleum operations within the Syrian

territory are authorized according to a form of production sharing agreement

(P.S.A.), which is granted by the government to the contractor and the Syrian

Petroleum Company (S.P.C.), the state-owned oil company established in 1974.

The majority of the country's P.S.A.s are equally split between the S.P.C. and

its partners. In general, Syrian P.S.A.s last up to 25 years and permit the

government to retain a certain percentage of the oil produced as

royalties.

2) Reserves, Production and

Exports — Historically Syria has never been a major player on world

oil markets. But at the same time, until the recent discoveries of natural gas

in the eastern Mediterranean, Syria has been the only real energy producer in

that part of the Middle East that encompasses Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, Syria

and Israel as well.

According

to the Oil & Gas Journal, Syria's proved reserves should be 2.5 billion of

barrels as of 2010 — among neighboring countries only Iraq (and the Kurdistan

Regional Government, the K.R.G.) owns a larger amount of oil reserves.

Before

the commencement of the hostilities between the government and the opposition

forces, production amounted on average to 400,000 bbl/d. At the world level Syria

was ranked 33rd for crude oil production, i.e., in 2011, 0.4 percent of the

world's total production. Already this percentage slid to 0.25 percent the

following year. This reduction was primarily due to two factors: the civil war

and the sanctions imposed by the United States (U.S.) and the European Union

(E.U). In February 2014, the Energy Information Administration (E.I.A.)

estimated that the overall Syrian crude and condensates production was 25,000

bbl/d, i.e., one-tenth of the pre-war production. This number included also the

production from the areas under the control of the factions opposing the

government.

On

a world scale, Syria's production was not very relevant, but still in 2009 the

government derived approximately 20 percent to 30 percent of its revenues from

oil. Before the civil war, Syria collected from oil around $4 billion per year.

Maximum production (610,000 bbl/d) was recorded almost twenty years ago in

1995. Since then, because of lack of technological development, depleted

reserves and petroleum product subsidies (according to the Middle East Economic Survey, Syria

spent $3 billion in subsidies in 2010), Syria started to import petroleum

products. And, already before the civil war, between 2001 and 2011, crude oil

production shrank by 41.2 percent. When between 2006 and 2011, Syria tried to hold

four licensing rounds (two onshore and two offshore) the results were quite

disappointing. Only in December 2013, the Syrian government signed a contract

for oil and gas exploration that might be of some importance. The counterpart

was the Russian company SoyuzNefteGaz and the contract was related to survey and

exploration for oil and gas in the continental shelf belonging to Syria from

the southern shores of Tartus to the city of Baniyas. The whole area is

approximately 845 square miles.

By

now, many international oil companies (I.O.C.s, among them France's Total,

which produced on average 39,000 bbl/d in

2010 and Anglo-Dutch Shell, which produced within the joint venture Al Furat

Petroleum Company (A.F.P.C.) 100,000 bbl/d as of May 2011) and national oil

companies (N.O.C.s) have ceased their operations in the country. At present, Western

companies are legally prohibited from working in the country.

Before

the start of the hostilities, Syria used to export over 150,000 bbl/d of crude

oil, whose 99 percent went to Europe (Turkey included). The main European

buyers were Germany, Italy and France, which, after the introduction of the

sanctions against the regime of President Assad, stopped buying Syrian crude.

In the end, in 2012, the country became a net importer of oil. Its exports are

now zero, at least through official channels.

3) Location of the Oil Fields — Syrian

oil exploration began in 1933 during the French Mandate thanks to the Iraqi

Petroleum Company (I.P.C.), but it was not until the 1950s that oil was

discovered in the eastern part of Syria around Souedieh in the Hasakah

Province. The oil sector took off only in 1968 when the production of the Karatchok

oil field was connected through a 663-kilometer pipeline to the port city of

Tartus on the Mediterranean Sea. A second area of production was then

discovered in the 1980s in the Euphrates Valley, from the city of Deir ez-Zour

to the border with Iraq. Syria did not begin exporting oil until

the mid-1980s. All of the country's exports are marketed by Sytrol, which is

the state oil marketing firm (it normally sells oil under 12-month contracts).

The

most important oil fields* are:

- Omar

Field (Deir ez-Zour Governorate) — 75,000 bbl/d.

- Thayyem

Field (Deir ez-Zour Governorate).

- Karatchuk

Field (Hasakah Governorate).

- Jbessa

Field (Hasakah Governorate).

- Rumailan

Field (Hasakah Governorate) —400,000 bbl/d.

- Souedieh

Field (Hasakah Governorate) — 100,000 bbl/d.

* Some production data are

missing so there are no clear data about the pre-war production of all of these

crude oil fields.

4) Types of Syrian Oil — Syrian

oil fields produce two different grades of crude oil:

- Souedieh Grade (a.k.a. Syrian Heavy) with 22 API

grade to 24 API grade and 3.9 percent of sulfur content.

- Syrian Light with

38 API grade and 0.68 percent of sulfur content.

Prior

to the 1980s Syria had produced only heavy grade oil. Then light oil was

discovered in the area of Deir ez-Zour in eastern Syria. These discoveries

attracted international interest and some consortiums were formed — among them

the Al Furat Petroleum Company (A.F.P.C.), which is a joint venture between the

S.P.C., Royal Dutch Shell, the Chinese National Petroleum Company (C.N.P.C.)

and India's Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (O.N.G.C.). Syrian Light, which is

light and sweet, has similar characteristics to Libyan oil.

In

2011, heavy oil accounted for approximately 60 percent of the Syrian crude oil

production. Syrian Light was mainly used by local refineries in order to

manufacture products for the internal market. Indeed, Souedieh grade is not

easy to process and according to a report by the Syrian National Council not

many refineries in the world are able to refine it. In practice, the refining

process is technically challenging and expensive. The majority of these skilled

refineries are in the U.S. and in the E.U., although, as of 2011, China was

upgrading some of its refineries in order to process heavy crudes as the one

produced in Syria. Many times, a limited number of markets available to import

and refine a specific type of crude oil mean that, in order to find alternative

purchasers, that crude oil has to be offered at a discounted price. The E.U.

boycott of Syrian oil is having an impact in reducing Syrian revenues because

Europe with its refineries was one of the most important purchasers — in 2011

Europe imported 3.6 billion dollars' worth of oil from Syria.

Syrian

oil fields are mature and, as such, already before the civil war they underwent

enhanced oil recovery (E.O.R.) techniques that use primarily natural gas. The

industry did not have many expected new discoveries in the years to come. As of

2010, according to the government, Syria should have also 50 billion tons of

shale oil reserves, but its development has now been postponed.

5) Pipelines — Syria

does not have any "working" international oil pipeline passing

through its territory. The third chapter will provide some information

regarding the two international pipelines that in the past decades had transported

oil across Syria. Neither is working today.

Instead,

Syria has four main internal pipelines:

- A

25,000-bbl/d pipeline from S.P.C.'s northeastern fields to the Tartus Terminal.

The pipeline has also a connection to the refinery in Homs.

- A

refined-products 500,000-tons/year pipeline system linking the refinery in Homs

to Damascus, Aleppo and Latakia.

- A

100,000-bbl/d spur line from the Thayyem Field and other fields to the T-2

pumping station, which is on the old Iraq Petroleum Company (I.P.C.) Pipeline,

a.k.a. as the Kirkuk-Baniyas Pipeline — see Chapter III for more information about this old pipeline. The T-2 pumping station is now controlled

by the Islamic State.

- A spur

line from the Ashara and El-Ward fields to the T-2 pumping station.

6) Refineries — The

country's two state-owned refineries, the one in Homs and the one in Baniyas,

are operating at reduced capacity for lack of oil to refine. Combined, the two

refineries are able to process 240,000 bbl/d (133,000 bbl/d in Baniyas and

107,000 bbl/d in Homs), but also when they were working at full capacity they

met only 75 percent of Syria's pre-war demand of refined products. Because of

damages to the infrastructure, it seems that currently the two plants are

working at 50 percent of their nameplate capacity — in particular, the one in

Homs is experiencing more difficulties because of its inland location. The

result is a lack of some refined products for the Syrian population, which, as

a consequence, is experiencing an increase in the prices of the few available petroleum

products. Naturally, all of the plans related to the construction of additional

refineries have been delayed or cancelled — among them there was the

construction by C.N.P.C. of an oil refinery near Deir ez-Zour capable of

handling 70,000 bbl/d to 100,000 bbl/d.

7) Export Terminals — The

two most important export terminals are:

- Baniyas,

which can accommodate Aframax tankers up to 120,000 deadweight tons and has a

storage capacity of 437,000 tons in 19 tanks.

- Tartus,

which can accommodate up to very large crude carrier (V.L.C.C.) of 210,000

deadweight tons. A pipeline connects this terminal to Baniyas.

There

is also a small terminal in Latakia.

CHAPTER III — Will Syria Be an

Oil Transportation Hub in the Future?

Introduction — One

initial preliminary consideration: Syria no longer is a Middle Eastern

transportation corridor. The country had lost this role in the 1920s and, only

in the past five years before the civil war, it had started to emerge again as

a railroad and road transportation hub with Turkey, Jordan and Iraq. The civil

war has now completely canceled these small improvements. The map and the slide below show the importance of Syria as a crossroads for international trade.

|

Syria at the Crossroads by Rich

Clabaugh/Staff

Source: The Christian Science Monitor

|

1) The Twentieth Century — For

the majority of the twentieth century, Syria's aspiration to be become an

energy hub toward the Mediterranean Sea and Europe were nullified by Middle Eastern

politics. And in the past sixty years, despite many difficulties, Syria has

been a partial transport hub only from the 1950s to 1982 (be it clear in a non

continuous manner) thanks to the Kirkuk-Baniyas Pipeline, which used to transport

oil from Iraq and the Trans-Arabian Pipeline (Tapline), which used to transport

oil from Saudi Arabia. The slides below provide additional details about these

two pipelines.

|

Kirkuk-Baniyas Pipeline — Source: Wikipedia

|

|

| Trans-Arabian

Pipeline — Source: Saudi Aramco Expats |

Until

the increase of oil prices in the 1970s, Syria earned more from the

transportation fees of these two international pipelines that crossed its

territory, than from its limited internal oil production. Then in 1972, Syria

and Iraq started to quarrel with reference to the tariffs applicable to the

transportation of Iraqi oil via the Kirkuk-Baniyas Pipeline. In the end, Iraq

decided to build the Strategic Pipeline linking Kirkuk to southern Iraq and the

crude oil that before flowed north now was directed south. Similarly, in 1980

Iraq and Turkey bypassed Syria when they built the Kirkuk-Ceyhan Pipeline,

Iraq's largest oil pipeline, in order to export crude oil from Iraq's northern

oil fields.

During

the Cold War years, diplomatic relations for Syria were quite complex because

of the country's alignment with the Soviet Union, the attacks against Israel

and its support of anti-Western terrorist groups. In specific, the political proximity

to the Soviet Union was a real issue for Saudi Arabia and the other Persian

Gulf countries. Things did not improve during the Lebanese Civil War. After the

end of the Cold War, Syria was still entangled in Lebanon and continued not to

be seen as a reliable partner by possible investors.

2) The Projects of the New

Century — In 2009, President Assad announced the "Four Seas

Strategy", which consisted in transforming Syria in an oil hub for

regional transportation between the Persian Gulf, the Black Sea, the Caspian

Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. It was a grandiose and far-fetched strategy, but

realistically it was impossible to achieve especially because it relied on

Turkey's support. And, the relationships between Ankara and Damascus in the

last years have deteriorated consistently. Currently, Turkey requires President

Assad to step down from power.

At

the end of July 2010, the Syrian government signed a memorandum of

understanding (M.O.U.) with Iraq in relation to the construction of two oil

pipelines for transporting oil from Iraq's Kirkuk Field. The signature of this

memorandum, which included a section related to the construction of a gas

pipeline from the Akkas Field in Iraq, was then followed in July 2011 by the

announcement of another gas deal between the two countries. Syria and Iraq

discussed these possible developments in the energy field thanks to the

improved relationships between the two countries after 2005 when Shia-dominated

governments started to hold on power in Iraq. Previously, the relationships

between the countries had been very difficult. This was especially true after

the Iranian Revolution in 1979, when Syria became one of Iran's most important

allies and Saddam Hussein's Iraq was Iran's sworn enemy.

3) Syria's Main Issues — One

important caveat: Because of the current civil war it is almost impossible to think of specific pipelines passing across Syria.

And,

before any energy projects involving Syria may be discussed the country has to

solve three main issues:

- First,

to maintain its current borders and not to be split among competing groups. The

second possibility would be a disaster because there would not be any possibility

of transporting crude oil through a divided territory. This is exactly what is occurring

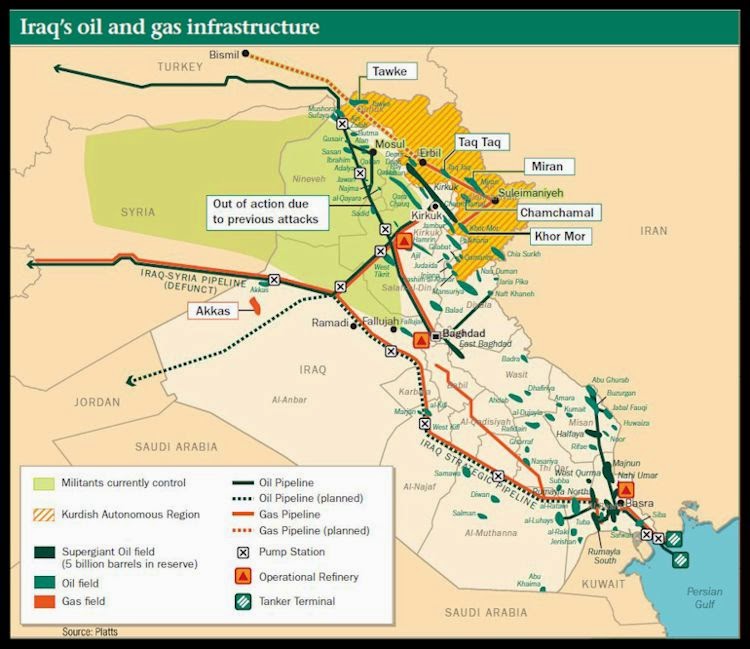

in Iraq where the Kirkuk-Ceyhan Pipeline has not been transporting oil through

the Iraqi section since March 2014. The reason is simple: The pipeline runs across

territory occupied by the Islamic State, which damaged the infrastructure.

- Second,

all of the security issues must be solved. Again Iraq is a good example of a

country that seemed pacified but that in reality had a lot of simmering

tensions. Today, Iraq is in complete turmoil and the very existence of the

country is not sure 100 percent. The result of this civil war in Iraq is that

the country is able to extract oil only from the southern fields (the K.R.G. is

apart) and then to export it via the Basra terminal. The reason is quite

simple: political stability and more security in the area. Syria needs to learn

the Iraqi lesson.

- Third, the

type of Syria that will emerge from the civil war will tell us a lot about the

possible future agreements with neighboring countries. The current deep split

between countries aligned with Iran on one side and countries aligned with

Saudi Arabia on the other side won't abase soon. According to who will be the

winner in Syria, there will probably be different investment agreements, which

not necessarily will follow sound economic foundations. This was the rule in

the past and will probably be in the future. In other words, it will be the

relationships between Syria (it's not clear what Syria will become), Iraq (it's

not clear what Iraq will become), Turkey and Iran that will decide the route of

the pipelines in the area.

So,

under the current circumstances only general considerations may be thought of

with regard to Syria's possible future role as a transportation hub for oil.

4) The Oil Transported Across Syria

Will Arrive from Iraq — From an economic point of view it seems

plausible that the oil that will transit through Syria will primarily arrive from

northern Iraq (and/or from Kurdish areas in Syria and/or in Iraq according to

the future political developments). Shipping crude oil from southern Iraq or

the Persian Gulf via pipeline to Syria and/or Turkey may be based on political

reasons or on the necessity of diversifying exports routes — a couple of years

ago many experts were talking of bypassing Hormuz in case of an Iranian

blockade of the strait — but from an economic standpoint it could be expensive.

Moreover, oil from southern Iraq is very close to the port city of Basra, which

is home to all of the six Iraqi ports, including the country's unique

deep-water port. And Basra terminals are currently able to export 2.4 million

bbl/d, which right now is practically the whole Iraqi oil exported.

When in 2013, Ankara and Baghdad discussed the

possibility of connecting Basra to Ceyhan via pipeline — current events in Iraq

have completely ruled out this project — the idea was to build only a new pipeline

between Basra and Kirkuk and then to pass oil to the Kirkuk-Ceyhan Pipeline,

which despite, a capacity of 1.6 million bbl/d, transported only 400,000 bbl/d.

In other words, the idea was to ship via the Kirkuk-Ceyhan Pipeline around

700,000 bbl/d — the Kirkuk-Ceyhan Pipeline consists of two twin pipelines, but at

that time only one leg was operational, while since March 2014 the

pipeline has been completely out of service from Kirkuk to the border with

Turkey. This project wanted to

reconstruct the Iraqi oil system of the end of the 1970s, which was based on

the Kirkuk-Ceyhan Pipeline and the Strategic Pipeline. The latter, which is now

not operational and severely damaged, was a north-south system,

consisting of a reversible 1.4 million bbl/d pipeline. Through the Strategic

Pipeline, Iraq could export Kirkuk crude from Basra and southern Rumaila crudes

from Turkey.

The idea of constructing a new pipeline between

Basra and Kirkuk might have been correctly motivated. In fact, once a pipeline

has been laid, like the Kirkuk-Ceyhan Pipeline, it has to be used. With

pipelines, idle capacity means economic losses. But, the complete construction and

the use of a new pipeline from southern Iraq or other Persian Gulf countries to

Syria and/or Turkey are very expensive tasks, especially in light of the

proximity of Persian Gulf countries to the sea. In general, crude oil is

cheaper to transport by tanker than by pipeline. The two slides below provide additional details about transporting oil via pipelines and tankers.

5) Syria's Four Complex Options

— The

final customer for the oil transiting through Syria or its neighboring

countries is primarily Europe (E.U.-28), whose first supplier in 2012 was

Russia with 33.7 percent of the E.U. crude imports. Saudi Arabia was the third

supplier with 8.8 percent and Iraq the seventh with 4.1 percent (Eurostat data).

Data show that Middle Eastern crude oil exports first and foremost go to Asia.

According to the Energy Information Administration (E.I.A.), in the year 2011

an average of 14 tankers per day passed out of the Persian Gulf through the

Strait of Hormuz. These tankers carried 17 million barrels, whose 85 percent

was plying to Asian markets. Last year, China overtook the U.S. as the world's

largest oil importer and Japan, India and South Korea are all in the first five

positions in this ranking. In the Middle East, only Iraq has a higher

percentage of exports toward Europe (20 percent) - geography tells us something.

All these data mean that with a European economy dormant it won't be easy to

find additional markets for crude oil shipped to Turkey or Syria via new

pipelines.

In

general, four are the possible options for Syria:

- To be a

transit country toward Turkey (final destination) — At

the time of this writing, the utilization of this route is completely

interlocked to a regime change in Syria. Given the current tense relationships

between Syria and Turkey, Ankara would not accept a deal with Syria unless

President Assad steps down and a Sunni-oriented Syria emerges.

- To be a

transit country toward Lebanon (final destination) bypassing Turkey — This

is a strange route. First of all, if oil is shipped to Lebanon it has to pass

across Syria. And if oil transits to Syria what is the reason not to export it

through the Syrian ports, which have been exporting oil for the last thirty

years?

- To be

the destination country bypassing both Turkey and Lebanon — Many

factors play a role in the implementation of this route, which Turkey does not

favor. But, if in both Syria and Iraq the incumbent governments could recover

their legitimacy with reference to respectively the whole Syrian territory and

the whole Iraqi territory this option could be implemented. If, instead in both

Syria and Iraq gained power two Sunni-led coalitions it would still be possible

to be implement this option, but in reality it would be more difficult in light

of Turkey's opposition.

- To be

excluded by pipelines that will arrive in Turkey — If

chaos continues in Syria this will be a very probable option. It already happened

twice in the past when the Kirkuk-Baniyas Pipeline and the Trans-Arabian

Pipeline were shut down. Investors (private and public as well) want stability.

Lacking this, there won't be any investment.

After

the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the Pentagon studied the possibility of utilizing

the oil route Mosul (Iraq)-Haifa (Israel). In fact, between 1935 and 1948 a

pipeline run from Mosul to Haifa, which at that time belonged to the British

Mandate of Palestine. After the creation of the state of Israel, Iraq shut down

the pipeline. This project — let's call it the fifth option, Syria excluded by

pipelines that will arrive to Israel — under the current circumstances is

absolutely not doable.

The

"Four Seas Strategy" is not a viable option because at least two of

its pillars, the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, are not achievable by Syria. A

simple look at the map well clarifies that the only real country that could

play a four-sea strategy is Turkey. Geography matters and it's difficult to

understand why crude from the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea should travel to

Syria's ports and not to Turkey's in order to reach Europe.

Moreover,

in this game of pipelines, Turkey, as well as Syria, wants to be a

transportation hub for oil and gas. And Turkey may eventually accept Syria only

as a transit country, but not as the final destination of pipelines that bypass

Turkey. It's quite understandable why Ankara is against the possibility of

reopening the Kirkuk-Baiynas Pipeline, which would challenge the Kirkuk-Ceyhan

Pipeline, notwithstanding that the latter is currently not working from Kirkuk to

the Turkish border, but only from the border between the K.R.G. and Turkey

where it receives Kurdish oil via the Iraqi Kurdistan Pipeline.

6) The Last Factor: Syrian Kurds

— Another

factor that will play an important role with reference to the future

development of Syria's oil sector is the emergence of an area under Kurdish

control in Syria's northeastern corner, which is the territory where most of

Syria's oil reserves are located. As it was explained in the first chapter,

it's thanks to the Syrian Kurds' resistance that Hasakah Governorate

with its oil riches has not fallen yet under the Islamic State.

|

| Syrian Kurdistan — Source: Wikipedia |

The

events of the last three years have shown that Iraqi Kurds want to manage their

oil and gas resources independently of Baghdad — some members of the K.R.G.

political establishment plainly speak of independence for Iraqi Kurdistan. It's

quite probable that something similar will happen also in the "Syrian

Kurdistan". If Syrian Kurds are able to repel the Islamic State attack, at

least they will request a slice of the oil pie, no matter what the Syria's

political system will be. For instance, Syrian Kurds could offer Iraqi

Kurdistan a direct route (Rojava Route), for its oil exports. In practice, the

K.R.G. could have a second route in addition to the one to Ceyhan.

It

is too early to understand whether there will be a new actor in the Syrian-Iraqi

oil chessboard in addition to the K.R.G. For the time being, apart from

fighting the Islamic State, Syrian Kurds are correctly maintaining a neutral

position between President Assad and the Syrian National Council (S.N.C.). In

specific, the P.Y.D., which is linked to Turkey's Kurdistan's Workers Party

(P.K.K.) considers the S.N.C as a pure marionette from Ankara. If the recent

vicissitudes of the K.R.G are any guide, Syrian Kurds will progressively assert

themselves as an element in the Syrian equation. In other words, this means that

they will look for more autonomy. And, for them, oil will be an important tool

as it has been with the K.R.G.