August 23, 2013

BEIRUT, Lebanon — The dispute between Erbil and Baghdad with reference to the energy riches located in the territory of the Kurdistan Regional Government (the K.R.G.) does not let up. In the last months the quarrel between the two parties has been centered around three main points — or at least these were the relevant issues which reached the headlines. In decreasing order of importance these are the three contending points:

A) Negotiating and Signing Energy Deals Within

the K.R.G. Territory — Baghdad affirms that it alone has the

right to negotiate and sign energy deals for the whole Iraqi territory,

the K.R.G. included, while since a couple of years Erbil has been on a deal-signing

spree with around 40 international oil companies (I.O.C.s). Considering that

within the K.R.G. recent data speak about the presence of 45 billion barrels of oil, i.e., one-third of Iraq's proven

reserves (proven reserves are those with a 90 percent certainty of being

produced at current prices with current commercial terms and government consent — they are known in the industry also as 1P) which are estimated at 150 billion

barrels and that the K.R.G. has 3 to 6 trillion cubic

meters of potential gas reserves, it's clear the importance of controlling

these resources.

B) The

Pipeline Between the K.R.G. and Turkey

— Erbil and Ankara are building in three different phases a

soon-to-be-completed pipeline system for crude oil (it is due to be ready by the end

of this year) that will bypass proper Iraq. This pipeline could be linked up to

the existing Kirkuk-Ceyhan Pipeline, which is instead controlled by the Iraqi central

government. The first phase connecting the Taqtaq Field to the Khurmala Field is

already operational and has an initial capacity of 150,000 bbl/d. The second

phase, which is also completed, concerns the conversion to an oil pipeline of a previously planned gas pipeline from Khurmala to Dohuk and has an initial capacity

of 300,000 bbl/d. The third and final step will be, it's currently under

construction, a pipeline between Dohuk and Fishkabur, which is on the Turkish

border. It will have an initial capacity of 300,000 bbl/d. But Kurdish government sources affirm that by

2015 following the installations of pumping stations the pipeline to Fishkabour will have a capacity of 1 million bbl/d.

C) Trucking the K.R.G. Oil and Condensate to

Turkey — According to the latest data, 30,000 to 50,000 bbl/d are trucked from

Kurdistan to Turkey. Of course, given the difficulties of trucking hydrocarbons,

the concerned quantity is not huge, but with no doubt it starts to have a

certain economic impact. In fact, the overall production of the K.R.G. is around 300,000

bbl/d — it is due to increase to 400,000 bbl/d by the end of 2013 — and this means that currently more than 10

percent of this quantity is transported with trucks to Turkey.

To

these issues some industry sources since the end of last July/beginning of

August have added a fourth one:

D) Trucking the K.R.G. Oil to Iran — Also

in this case there are some important geopolitical considerations involved in

this activity. In fact, in addition to the quarrel between Erbil and Baghdad,

trucking hydrocarbons to Iran means turning down and contravening Western

countries' sanctions against Tehran. The West passed these sanctions as a response to Iran's attempts at developing a nuclear program.

It's

important to clarify once and for all one thing: This trucking activity between

Iraqi Kurdistan and Iran is not new. Smuggling Iraqi Kurdistan's oil to Iran is an activity that has been around for the last years and that only at different

intervals — normally one time per year — has reached the headlines to be immediately after consigned to oblivion for the following months.

Once again this summer, industry sources affirmed that it seemed that Iraqi Kurdistan was continually (if not continuously) trucking domestic crude oil to a couple of Iranian ports, Bandar Abbas and Bandar Imam Khomeini. The first one is a port city located on the southern coast of Iran very close to the Strait of Hormuz, while the second one is a port city located in the northern part of the Persian Gulf close to the border with Iraq and in front of Kuwait. Then, from this two ports crude oil should be exported to Asia either after one stop in Fujairah (U.A.E.) or one stop at other ports in the Persian Gulf. A possible interpretation for understanding this second hydrocarbons route — the first route trucks hydrocarbons to Turkey — is that Erbil has to find a balance between its two powerful competing neighbors Turkey and Iran. For such small an entity like the K.R.G., at least for now, it's of paramount importance to maintain friendly relations in its neighborhood, especially in light of the strained relations it now has with Baghdad.

|

|

Photo of Ayman Oghanna for The New York Times (2010)

|

Once again this summer, industry sources affirmed that it seemed that Iraqi Kurdistan was continually (if not continuously) trucking domestic crude oil to a couple of Iranian ports, Bandar Abbas and Bandar Imam Khomeini. The first one is a port city located on the southern coast of Iran very close to the Strait of Hormuz, while the second one is a port city located in the northern part of the Persian Gulf close to the border with Iraq and in front of Kuwait. Then, from this two ports crude oil should be exported to Asia either after one stop in Fujairah (U.A.E.) or one stop at other ports in the Persian Gulf. A possible interpretation for understanding this second hydrocarbons route — the first route trucks hydrocarbons to Turkey — is that Erbil has to find a balance between its two powerful competing neighbors Turkey and Iran. For such small an entity like the K.R.G., at least for now, it's of paramount importance to maintain friendly relations in its neighborhood, especially in light of the strained relations it now has with Baghdad.

After

the industry sources had voiced their comments, a source with the K.R.G Ministry of

Natural Resources responded that the Kurdish government was absolutely not

involved in these trucking operations to Iran. Moreover, what is exported is

not crude oil, but black oil, which is any refined products that have less

economic value than crude oil per unit price. In specific, added the source,

this black oil going to Iran was a residue of the filtering process happening at

the Baiji refinery, located in proper Iraq. Baiji is a city in northern Iraq,

approximately 130 miles north of Baghdad on the main road heading to Mosul. The

city in the energy business is well known for its oil refinery, which is the

largest in Iraq. In other words, at least according to Erbil, who is doing

these trucking activities are only private companies that have previously contracted

with Baghdad. Now this business has been going on in this way for

years.

In

reality, in what is today's Iraqi Kurdistan, the Kurds have been in this trucking business

since the 1990s. They began more or less when economic sanctions were imposed

upon Iraq following its August 1990 invasion of Kuwait. For this reason, it's

very difficult to think that behind this trucking activity there can be only

private companies working under a sort of commercial agreement with Baghdad. Over

the last years not only has evidence been collected showing that the Kurdish

authorities have been well aware of the smuggling, but also it's evident that they have facilitated

it (surely the K.R.G. Natural Resource Ministry and the Finance Ministry). Summing

up, the profits of the oil smuggling have been split between all the involved

actors:

A) the

two major parties in the K.R.G.: the Kurdistan Democratic Party (K.D.P.) and the

Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (P.U.K.),

B) the

energy companies working in the K.R.G. and

C)

politicians in Baghdad.

In

other words, everyone has had a slice of the economic pie. This is also a good

explanation of the low profile that the involved parties have given to this oil

smuggling. In fact, at every outbreak of public resentment, the K.R.G. has always repeated

the same story, i.e., that private companies were doing this business helped by the fact

that Iraqi crude oil was subsidized and might be sold with good profits in neighboring Iran.

Last year, Minister of Natural Resources Ashti Hawrami admitted that only fuel oil and byproducts like naphtha were transferred to Iran. This activity was related only to the K.R.G. oil processed at two privately owned

refineries that supplied the local market and a power plant. For the minister,

the profits of shipping fuel oil and byproducts to Iran were utilized simply

to cover the costs incurred by the foreign companies working in the K.R.G.

In fact, the Kirkuk-Ceyhan Pipeline, the main export route, was not always open

because of the ongoing dispute between Iraqi Kurdistan and Iraq. Last but not least,

the minister added that these revenues were separated from the K.R.G. finances

and put into a separate account so that in the future they could be reconciled

with Baghdad. And of course, the official political speech in the

K.R.G. was repeating constantly that Erbil was committed to stopping this business. At the same time, in Iraq, the government of Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki was menacing of cutting the K.R.G. budget, if this trucking route would not have stopped soon.

Assessing

the trucked quantity to Iran is not easy, the latest data give an amount as

large as 30,000 bbl/d. And it's not clear

in what proportions this quantity is split between the two ports. But an

initial consideration stands out immediately: Transporting via truck for long distances

oil is not very economically viable. Pipelines

in the majority of cases are the only economical transportation means for oil

in order to reach sea ports or the final centers of consumption. And this

consideration is particularly true for remote oil fields and for land-locked

areas. At this regard, last June the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research

released a report where it underlined the fact that pipelines are the safest and

most cost-efficient way of moving oil and gas and that a person is more likely

to be struck by a lightning than to pass away in a pipeline-related accident.

From this basic reflection, it's possible to understand that the business we are

talking about between Iraqi Kurdistan and Iran is not a huge business, although

it's a good business.

At the moment there are two border gates between the K.R.G. and Iran, the Haji Omaran

Border Gate (through the K.R.G. Road 3) and the Bashmeg Border Gate (through the

K.R.G. Road 46). Both are located in the Sulaymaniyah Governorate. Reaching

with trucks the two above-mentioned Iranian ports from the K.R.G. (let's assume from the

Taqtaq oil field, using one of the above-mentioned border gates) and/or Iraq's

Baija (if we give full credit to the K.R.G. authorities and we consider the trucking

business as only a private activity) is indeed a long road.

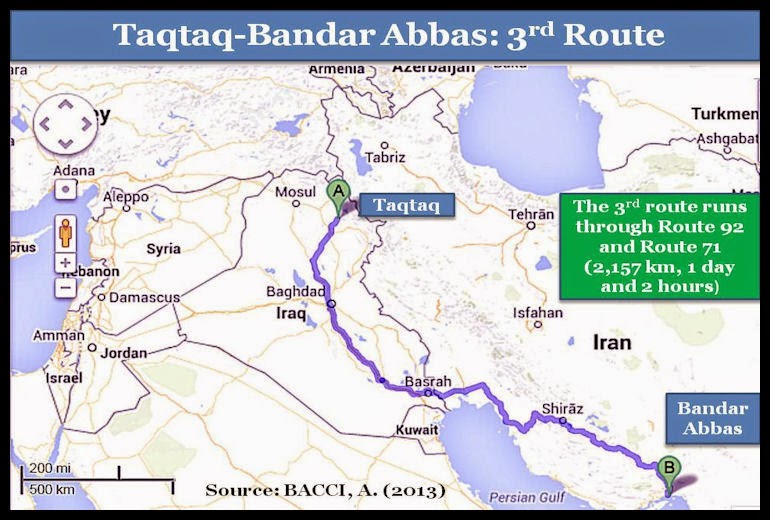

Let's

consider the journey from the Kurdish oil fields to Iran's Bandar Abbas passing

the frontier with Iran at the Bashmeg Border Gate (using instead of this the Haji

Omaran Border Gate would not change consistently the substance). If trucks choose this road

they will run Route 71, which after 1,954 kilometers and 21 hours and 48 minutes will

take them to their final destination, Bandar Abbas. (For the sake of completeness, it's worth mentioning that there could be an almost identical journey via A-2 and Route 71. Through this second option, trucks would enter Iran at the Khanaquin Border Gate, east of the city of Samarra, in proper Iraq). Instead of crossing at the

Bashmeg Border Gate (still not considering to pass through the Haji Omaran Border Gate or to do the journey via A-2 and Route 71) there

are two other possible and really different alternatives: running through Route 92 (2,017 kilometers, 1

day and 1 hour) or running through a combination of Route 92 and Route 71

(2,157 kilometers, 1 day and 2 hours). These two alternatives, if almost equivalent in

terms of kilometers and required time, involve traveling long distances within

Iraq. In specific, the second one makes the trucks enter Iran approximately 250

kilometers south of the Bashmeg Border Gate (point to point). The third traveling

option makes the trucks enter Iran even after Basra, in southern Iraq.

The involved distances would be more or less the same if trucks departed from Baiji, which is located only 172 kilometers southeast of the Taqtaq area. In fact, from Baiji to Bandar Abbas there are two options: the first one through Route 71 (2,055 kilometers, 22 hours and 26 minutes) entering Iran at the Khanaquin Border Gate (east of the city of Samarra) and the second one through Route 92 (2,024 kilometers, 23 hours and 35 minutes) entering Iran after Basra. It should be noted that according to Google Map navigator from Baiji, going south, the natural entering point to Iran is always the Khanaquin Border Gate. And the same happens if the departing point were Kirkuk that is on the road leading to the Bashmeg Border Gate (moreover, passing via the Khanaquin Border Gate could also be acceptable if trucks departed from Taqtaq because it would add only 100 kilometers and 1 hour than passing via the Bashmeg Border Gate through Route 71). In other words, following the K.R.G. official declarations (trucking is only related to black oil loaded at the Baiji's refinery) it's quite unusual that trucks completely loaded at the departing point (Baiji) have to travel north to cross into Iran at the Bashmeg Border Gate or even at the Haji Omran Border Gate which is even further north.

Anyway, putting aside logistics considerations, thinking of stopping this trucking activity, notwithstanding the sanctions versus Iran, is at least for now simply wishful thinking. According to Joel Wing, a long-time expert of Iraq:

... there are no incentives for Kurdistan to stop

it. First, the profits go directly to the two ruling parties, providing them

with an independent source of funds outside of the portion of the budget they

receive from Baghdad. The trade is also split up between the two with smuggling

to Turkey dominated by the K.D.P., while the P.U.K. handles Iran. In turn, a

percentage of the money goes to companies that are producing in Kurdistan.

The only solution for halting smuggling would be for Iraq to finally draft and sign the since-long-time-needed Federal Oil and Gas Law. But relations between Erbil and Baghdad have soured since last March when the Federal Government passed the 2013 Budget Law. Through this law the budget allocation for the K.R.G. was $3 billion short of what Erbil expected. Subsequently, the direct consequence of this federal law was the K.R.G. "Law of identifying and obtaining financial dues to the Kurdistan Region — Iraq from federal revenue", a.k.a. the Financial Rights Law of April 2013. The aim of the law is to create a mechanism for establishing the amount Baghdad owes to Erbil and, especially, defining in the framework of the Iraqi Constitution a remedy if the central government does not transfer the established payments to Erbil. This remedy means in practice direct exports of oil and gas produced in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The central

point is that considering the great turmoil in the Middle East — and of course in Iraq, a country that

risks being fragmented into sub-states — the Kurds have started to think of a

possible secession from proper Iraq, and of course oil and gas are the tools in order to get to this result. Once Erbil abandons its semi-autonomous status for a

possible journey toward independence, it will be very normal that it will develop its own

foreign affairs agenda. And consequently that it will try to maintain political and

economic relations with Turkey and Iran, two of the candidates as leading countries in the Middle East. In other words, the Kurds have to strike

a balance. On the one side, the last 12 months have provided Erbil with leeway

and blessing from Ankara in order to develop energy relations between

Turkey and the K.R.G. notwithstanding Baghdad's and Washington's opposition —

Ankara is strongly looking to diversify its oil and gas sources. On the other

side, now Erbil would like to obtain a similar green light from Tehran. But because of the economic sanctions imposed on Iran, the process will

be much slower. A final consideration: Smuggling hydrocarbons is only the

initial step of a story that if continues in the long run, will unroll pipelines

between the K.R.G. and Iran, similarly to what is currently happening between the K.R.G. and

Turkey.