November 25, 2013

BEIRUT,

Lebanon — When last summer Iraq's Ministry of Oil accused Anglo-Dutch Royal Dutch Shell

(R.D.S.) of more than $4.6 billion of lost revenues (with an

aggregated loss of production amounting to 44 million barrels of oil) in

relation to the company's operations in the Majnoon oil field in southern Iraq,

one might have expected a possible stop to additional new ventures of R.D.S. in

Iraq. Instead, the Anglo-Dutch company is currently closing a preliminary deal with Iraq for a $11 billion petrochemical

complex. Considering the unrest that Iraq is currently experiencing,

this Shell's additional involvement in the country is good news.

This month French-American Schlumberger and U.S. Baker Hughes,

two oilfield service providers have stopped their operations in Iraq as a

consequence of the religious protest at the British Petroleum-operated Rumaila

oilfield. Until now, R.D.S. has not experienced social unrest at the

Majnoon oilfield, which is its most important operation in the country.

After closing this deal, R.D.S. will be involved in Iraq in four relevant

operations:

- Investing in the $11 billion petrochemical Nebras complex.

- Collecting gas from southern oilfields.

- Being the junior partner at the West Qurna-1 oilfield.

- Being the operator at the Majnoon oilfield.

Let's

now examine these four operations R.D.S. has in Iraq, giving of course more

attention to the Majnoon oilfield.

1)

THE NEBRAS PETROCHEMICAL COMPLEX

The

preliminary deal for this petrochemical complex is an important step for R.D.S.

because it marks for the company the first major investment in Iraq's

downstream sector. The downstream sector refers to refining crude oil and

processing and purifying natural gas, as well as marketing and distributing products derived from crude oil and natural gas. Baghdad and R.D.S. are close

to signing a heads of agreement—sources say that it's a matter of few weeks.

Still in relation to this project, in April 2012, the company had already

signed a memorandum of understanding for a feasibility study for a factory to

produce the plastic building block ethylene.

This

project is called Nebras, which means "beacon of light." If

accomplished it will be part of Iraq's investments aimed at establishing a petrochemical industry in the country. In fact, recent estimates explain that

Baghdad wants to find $35 billion to $50 billion hoping in the end to produce 10 million tons of petrochemical products per year. One of the main positive

points of the go-ahead for Nebras complex is that thousands of jobs might be created. According to Shell's country chairman, Hans Nijkamp, for

every job in the complex there would be 162 outside the plant.

2)

COLLECTING GAS FROM SOUTHERN OILFIELDS

Exactly

two years ago, in November 2011, Shell signed a $17.2 billion deal with Iraq for collecting

and processing natural gas from three of Iraq's giant southern

oilfields—Rumaila, West Qurna-1 and Zubair.

For this purpose, the Iraqi government created the Basra Gas Company (B.G.C.), participated by

Iraq's South Gas

Company (51 percent), R.D.S. (44 percent), and Japan's Mitsubishi

Corporation (5 percent). According to the deal, this 25-year-long joint

venture has first to collect, treat, and process raw gas and then to sell it and

the associated products, such as, condensate and liquefied petroleum gas (L.P.G.,

is a flammable mixture of hydrocarbon gases and it's used as a fuel in heating

appliances and vehicles), domestically and, if production exceeds the internal

demand, also abroad.

At

the time of the signing, southern Iraq produced around 1 billion cubic feet

(BCF) a day of associated gas, but of this amount, some 700 million cubic feet (MMCF)

were flared, which meant wasting millions of dollars of the country’s

resources. Associated gas was normally flared, or burned off, but, of course,

given the dire energy needs in Iraq, Baghdad does not want to waste

it anymore. Apart from a positive economic impact from supplying additional

energy, collecting natural gas means reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The

joint venture started its operations last May. Shell and Mitsubishi have a 35

percent tax on their profits. According to the released data, this project

is the world's largest gas-flare reduction project. Under the signed contract

the B.G.C. has to sell the processed gas to the state-owned South Gas Company.

The planned target for this project is to process 2 BCF per day from a

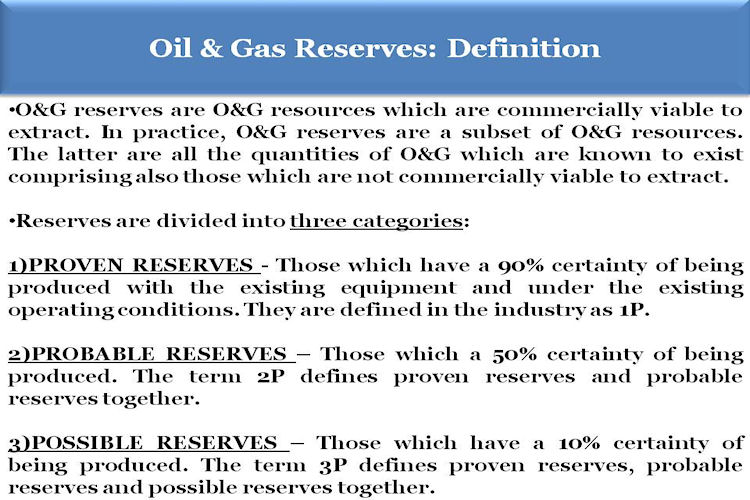

current amount of 400,000 MMCF. Iraq's current proven reserves of gas are

estimated at 128 TCF, but, adding also the probable gas reserves, the total

amount could reach the value of 325 TCF.

3)

BEING THE JUNIOR PARTNER AT THE WEST QURNA-1 OILFIELD

Shell

is the junior partner at the supergiant West Qurna-1 oilfield located 50

kilometers north-west of the city of Basra, in southern Iraq. West Qurna-1 owns 8.7 billion barrels, and by the end of 2013

current production should reach 600,000 barrels per day (bbl/d). The main

partner of this twenty-year service contract is U.S. ExxonMobil

(60 percent), Iraq's Oil

Exploration Company (25 percent) and R.D.S. (15 percent).

It

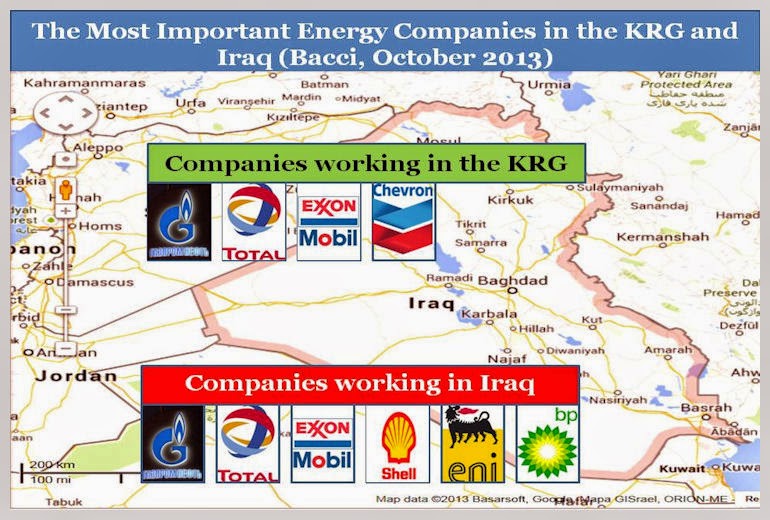

is possible that, in the next months, Exxon will sell part of its stake to appease its tense relations with the government in Baghdad. In fact, in October 2011, ExxonMobil entered the Kurdistan Regional

Government (K.R.G.) energy sector acquiring six exploration blocks, and, with this move, it upset Baghdad, which considered—and still considers

today—those deals as plainly illegal. In addition to this, Baghdad

immediately menaced to strip Exxon of the West Qurna-1 contract, if

the U.S. oil company did not relinquish its operations in the

K.R.G. ExxonMobil at the end of 2012 had expressed the intention of

selling all its stake, then, in the spring of 2013, it announced the

intention of increasing its investment in West Qurna-1, while recently (summer 2013) it seems that the company wants

now to sell more than half of its 60 percent stake. Petrochina

could buy a 25 percent stake of West Qurna-1 and Indonesia's Pertamina

a 10 percent stake. Considering the new quotas, Exxon would still maintain

a 25 percent stake.

|

| Iraq’s Oilfields Map — Source: www.esplift.com |

West

Qurna-1 was part of the first Iraqi licensing round (2009, with

the bidding and award of the contracts in June 2009) and it was not initially awarded. Only some

months later, in October 2009, the consortium led by Exxon (and including Shell

as junior partner) was awarded the oilfield (with final signature in January

2010). In practice, in the months after the auction, what later became the winning consortium accepted a reduced fee per barrel

in comparison to what previously it had offered on the day of the failed auction for West

Qurna-1. In fact, the Exxon-led consortium initially had requested a fee of $4

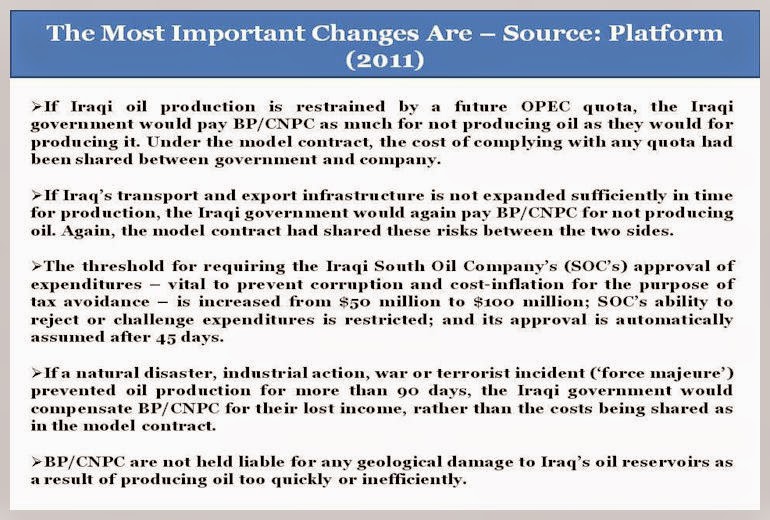

per barrel, but after some months it accepted a $1.90 per barrel. Something similar happened to the British Petroleum-led

consortium for the Rumaila oilfield (also on offer through the same

licensing round) although in this case the field was awarded immediately (the

only field in the first licensing round awarded as a direct result of the

auction out of eight) in the July 2009 auction for a fee of $2 per barrel. What

happened later was that the contract was renegotiated in the

following November with an improvement to the contractual terms for

British Petroleum (BP). (For more information see: BACCI, A., BP Continues Investing in Iraq. With T.S.C.s

the Devil is Always in the Detail(s) (October 2013).

The production plateau when the Exxon-led consortium signed

the contract was 2.325 million bbl/d, and in November 2010 it was raised to

2.825 million bbl/d thanks to the discovery of new reserves. Behind

this plan there was the necessity for the Exxon-led consortium to increase

productivity in a fast manner in order to recover costs. To get to this

point it was necessary to drill new wells, revamp old ones, and proceed with

water injection projects. Now that the Iraqi government is revising the production

plan for all the southern oilfields—reductions have already been agreed upon for the

two oilfields Zubair (in May 2013) and West Qurna-2 (in January 2013)—ExxonMobil and its partners are discussing about reducing

the plateau production from 2.825 million bbl/p to 1.8 million bbl/d.

4) BEING THE OPERATOR AT THE MAJNOON OILFIELD

4) BEING THE OPERATOR AT THE MAJNOON OILFIELD

Majnoon

is one of the supergiant southern oilfields, which are crucial for Iraq in order

to at least double its oil output, which hovers now around 3 million bbl/d. The

operator is Shell with a 45 percent stake, while Malaysia's Petronas

and Iraq's Ministry of Oil have respectively a 30 percent and 25

percent stake.

Majnoon, which owns more than 13 billion barrels, is located in Basra Governorate in southeast Iraq—60 km northwest of the port city of Basra. The field, which

was discovered in 1975, extends northward toward Maysan Governorate. It's

long approximately 52 kilometers, and it's wide 15 kilometers. Its

territory lies for the most part under man-made islands in the Hawizah Marshes

(these are a Ramsar area under the aegis of the U.N.), close

to the Iranian border.

Historically,

France's Total

had shown a certain interest for this field since the 1990s. At that

time, it signed a never implemented agreement with President

Saddam Hussein for developing the field. Later, in

2002, President Hussein annulled this agreement. In 2007,

Total signed together with U.S. Chevron an agreement to explore the field.

When after the Second Gulf War, Iraq started auctioning its

oilfields, Majnoon was then part of the ten oilfields auctioned in 2009 through the second post-war licensing round. The result

of the second bidding round was partially positive because only three oilfields were

not awarded. In fact, for them no bids were submitted (quite relevant was the

non assignment of the Baghdad oilfield holding 8 billion barrels). Shell and

Petronas beat a rival bid from Total and China National

Petroleum Corporation (C.N.P.C.) and signed a 20-year service contract for the Majnoon oilfield. With

reference to the signed contract, the two companies should receive $1.39 per

barrel, and, at least initially, the target was to increase oil production to a

plateau of 1.8 million bbl/d by 2017. Shell started in 2012 some talks with Baghdad with the

aim of reducing the targeted oil production to 1 million bbl/d.

When

the winning consortium took possession of the oilfield, oil production was at 46,000 bbl/d—it's

important to underline this number out of a 13-billion-barrel oilfield. Subsequently, in

September 2011 production almost doubled reaching 75,000 bbl/d, but huge problems

emerged in 2012. At that time, the maximum production was 54,000

bbl/d because of some pipeline constraints, but, in reality, the average

field production was around 18,600 bbl/d. In June 2012, started a

shutdown to bring online new production facilities.

The

Majnoon oilfield at reservoir level is not particularly difficult to be worked on by so qualified a company as Shell. “There is some hydrogen sulfide, but we can cope with that. The difficulties lay mostly elsewhere,”

affirms Davesh Patel, operations and asset manager for Majnoon. In fact, the

real difficulties lay out of the ground. And many were the problems that

that the consortium has faced in the last months. Among them:

- Infrastructure limitations—The existing 28-inch pipeline was not able to satisfy the requirements of an increased production. The delay in the construction of the pipeline was probably one of the reasons forcing the consortium to miss the 2012 target of 175,000 bbl/d. Last year, Shell asked Iraq for a waiver to start recovering costs, if Majnoon had not meet its first commercial production target by year-end (pushing on the fact that Iraq could fail to provide an export route to handle Majnoon's output), but this request was rejected. Iraq stressed the point that dues would be paid only after first commercial production (F.C.P.). The construction of a new pipeline was quite controversial because in 2011 Iraq, Shell and Petronas awarded Dubai-based Dodsal Group a $106 million contract to build a 79-kilometer (50-mile) pipeline from the Majnoon oil field to a crude storage depot near Zubair in southern Iraq. The problem was that the Ministry of Oil discarded the deal on the basis of high costs and handed over the task to an affiliate to the Ministry of Oil. China Petroleum Pipeline (C.P.P.) was then contracted for building part of the pipeline.

- Mine-clearance activity—The oilfield is located close to the Iranian border and, considering the history of that area (first the Iran-Iraq War and then the First Gulf War), there are still in place many explosive war remnants. A relevant mine-clearance activity has to be implemented in order to ensure safe oil operations. As of fall 2013, more than 14,000 explosive remnants have been cleared.

- Delays at customs—Shell is still very concerned about the complex and long customs procedures. As an example, the company is very concerned about being successful in securing enough rigs to drill the 1,000 wells planned for its Majnoon oilfield. Mr. Nijkamp recently said, “Unless we work together with the Iraqi government and fix these port systems and customs, you will not see the ramp-up the Iraqi government is targeting with production.” Summing up, importing goods takes a lot of time and also securing visas for sub-contractors requires an excessive amount of time. This is a problem common to all the companies which have to import goods from abroad into Iraq.

- Bad weather conditions—During some months in 2012 weather conditions were inclement and partially hampered the development activities. It's worth remembering that in those months oil exports from both Kuwait and Iraq were disrupted for inclement weather (storms and high winds). As a result, Basra terminals consistently reduced exports.

- The discovery in December 2012 of an ancient Persian archaeological site—This was not a surprising event because in the vicinity of the Hawizah Marshes there are archaeological, cultural, and historical sites. Many of these sites belong to the Sassanian and Islamic cultural periods. But no real assessment of their status has been recently conducted.

|

Technician on his way back from daily

routine check. Majnoon Oil Field — Central Processing Facility — Source: Shell

MENA Magazine Nov. 2013

|

With

no doubt the company never thought of experiencing so many a problem at this

oilfield. In relation to the company's 2013 development program, output was

scheduled to rise over 200,000 bbl/d over 2013, and now it's possible to affirm

that this target has been reached. In fact, last October, the production of the Majnoon oilfield rose to

175,000 bbl/d, which is the established F.C.P.—this is a

very important target because it's the level from which the consortium may

start to recover costs. Now, according to Baghdad, current production should be

around 200,000 bbl/d, which is approximately the agreed-upon target for

2013.

CONCLUSION

What

will happen in the future in Iraq—and in this country also a few months is a

long period—is not clear (let's think of the current unrest and the

tensions with the K.R.G.). All this said, it's possible to affirm that R.D.S.

is implementing in Iraq important and diversified oil and gas operations, of which the Majnoon oilfield is the crown jewel. The company has decided

not to invest in the K.R.G., and this strategy of being focused on Iraq proper only is permitting R.D.S. to be one of the main players in Iraq.

Some

tensions between an energy company and the host country are part of the normal

development of big business ventures (and those of the energy business

certainly are) in which delays may always occur for many unforeseen reasons. So,

it should not be a surprise that an additional new contract has

recently been signed between Shell and Baghdad, and that, only a couple of months

after a summer ridden by tense relations between Shell and the Ministry of Oil, the company

has been able to reach the planned production target, partially catching up

with the previously missed deadlines.

|

Sunset at Majnoon oilfield — Source:

Shell MENA Magazine Nov. 2013

|