October 22, 2007

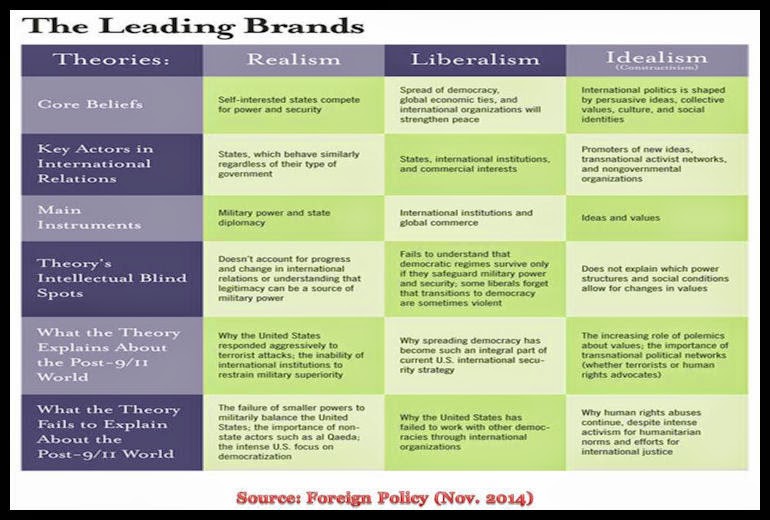

ABSTRACT — The

twentieth century saw a confrontation between two different schools of thoughts

with reference to the structure of international politics. The two schools were

realism and liberalism. The aim of this paper is to show that a sharp

distinction between the two schools is not very useful in order to understand

the mechanisms of international politics. In particular, the idea of the paper

is that the roots of international politics are based in the theory of realism,

but then international liberalism can become a very important means to mitigate

the harshness of a pure international relations theory based only on realism.

Introduction — After the

dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991 there has been an important

revival for liberal internationalism considered once again (after its apogee in

the 1920s and 1930s) as the main theory in order to understand the way

international politics is structured. From the end of World War II until 1991,

liberal internationalism had received scarce consideration. Probably the

demise of international liberalism had begun before the end of the war. In

fact, in 1939 Edward Carr wrote The Twenty

Years’ Crisis[i]

a volume that was a powerful attack against liberalism. After the ruins of World

War II, liberalism was easily outpaced by realism and authors like Edward Carr and

Hans Morgenthau were at that time the most studied. More or less this trend had continued

until 1991. The world during these 47 years had seen the confrontation of the

two big ideological blocs: the West centered on the U.S. and the East on the Soviet Union. All international politics in its deep essence was filtered

through the lenses of the Cold War between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. Then,

suddenly in December 1991, the Soviet Union disappeared and the U.S. was the

only remaining superpower.

Excessive

Optimism — A new phase of international relations has started in December

1991. According to Francis Fukuyama, the demise of the Soviet Union and the fall of

the Berlin Wall well explain that liberal democracy is the only form of

government that can guarantee a good standard of living for the majority of the

world’s population. This idea is probably right and the fact that democracy and

liberalism have been accepted all around the world confirms that liberalism and

democracy can spread a better standard of living through a larger percentage of

people. In particular, Scott Burchill clearly states that “Fukuyama believes

that progress in human history can be measured by the elimination of global

conflict and the international adoption of principles of legitimacy which have

evolved over time in certain domestic political orders”.[ii]

According to liberal internationalists the more shared principles based on

democracy and liberalism will be spread among states, the more these states

will not be interested in waging new wars. In other words, with the end of the Cold

War there should be a sort of tendency for states to operate correctly and to

promote the wellness for all the actors present on the international arena.

After sixteen years this vision appears to have been too optimistic. With the end of bipolarity, many conflicts began in different areas of the world and among the most important it is necessary to mention: Rwanda, Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq. Of these five conflicts only the Second Gulf War may be considered as a real international conflict. With reference to the other conflicts — Afghanistan included — the inception of the hostilities was related to an internal civil war eventually transformed into an international conflict. For instance, with reference to Afghanistan, the war fought there from October 2001 onward by the U.S., should be considered as another ring of a chain of events that started in 1978 when the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (P.D.P.A.) overthrew President Mohammed Daoud Khan. Behind the P.D.P.A. there was the Soviet Union, but technically it was still an internal issue. The real internationalization would happen the following year in December 1979 with the invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet Union. And Afghanistan is the real turning point that should be understood in order to explain the post 1991 world.

Afghanistan 1978 — Given a not very clear understanding of the events that started in Afghanistan in the far 1978, liberal internationalists in 1991 misread the future of international politics. In particular, already in 1979 it should have been understood that it was emerging a Muslim movement (similarly to what was happening in Iran) that was claiming power and that was not easily linkable to either the U.S. (which was financing it) or obviously to the U.S.S.R., which was fighting this movement. In other words, at that time — twelve years before the end of the Cold War — these events were clear signals of the fact that after the end of the confrontation between the West and the East many other potential conflicts (that in the previous decades had been put aside by the Cold War) would erupt in different areas of the world and especially in the Muslim regions.

In addition to this point, another misunderstanding of the liberal internationalists after the end of the Cold War was to have excessive hopes with reference to the power of the international organizations, in prima facie the United Nations. According to this vision, the end of bipolarity should have permitted to the United Nations (U.N.) and the other related international organizations more freedom and more capacity to intervene. This has not happened, while, on the contrary, in the last years, the legitimacy and effectiveness of the U.N. system has been questioned widely. In particular, the massacre of Srebrenica may be considered as the de profundis of the U.N. Instead, the end of bipolarity has meant to have one superpower and several strong emerging countries at the regional level. Among these, there are China, India and a renovated Russia.

Realism — In reality, international politics is still today strongly based on the assumptions of realism. With reference to the fact that realism is accused of not considering other actors than the states, this critique is not entirely true. Already in 1970, Hans Morgenthau, when writing about globalization, had a clear idea that in the following decades the role of the state would be diminished[iii]. This is the only point that probably the school of realism should have clarified extensively. In fact, today’s international politics sees the emergence of new actors different from nation-states. These new actors are present at different levels of modern society, but are capable of voicing their ideas. This ability is due to two reasons: 1) very powerful new technologies (Osama Bin Laden without the new technologies would have never become what he is today) that permit to aggregate ideas and people while before it was much more difficult; and 2) with the end of the Cold War many ideas may now be expressed disenfranchised from the confrontation West-East that before permeated every aspect of the political dialogue (domestically and internationally). Given these reasons, corporations, interest groups, nationalists and fundamentalists since 1991 have had a larger field of action. Obviously, this phenomenology in some circumstances is a powerful tool for good ideas while in some other circumstances it contributes to today’s political international instability.

Realism has been attacked in the last decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union with reference to the fact that it does not encompass economic considerations in its way of explaining international politics. But according to an in-depth analysis are we sure that economic considerations are a target and not just a means in order to increase the realization of the self-interest of every single nation? Probably, economic considerations are a means. One classical example that supports this idea is the construction of the European Union (E.U). The E.U. was born thanks to economic reflections related to specific economic sectors (the six original members understood that specific unions in different economic sectors were the only real viable options to be all better off). So the harmony of interests — if eventually present — was a minority element in the decision of creating the European Coal and Steel Community (1951), the European Economic Community and the European Atomic Energy Community (1957).

But, if we want to support better this idea, we have to pass from the Europe of the 1950s to the Asia of 1990s and 2000s. During these years, Asia has had an incredible economic growth. In fact, China is today a regional power and India is on that path as well. Also, other countries are gaining good economic results, so that it is possible to affirm that, notwithstanding the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Asia is a continent in big economic expansion. Although growing economic and diplomatic integration, “Asia has embarked upon a new arms race. And with China, Russia, Japan and India all feeling their strength, the region’s powers are beginning to divide into two broad alliances.”[iv] One alliance is formed by Japan, India, the U.S. and Australia, while the other is formed by China, Russia, Central Asian nations and Pakistan. This situation could have already been partially understood in 1995 and 1996 when China sent some missiles close to the coasts of Taiwan and advertised its military capacities. But after more than a decade many things have changed. A new economic architecture has been shaped and many of the Asian countries “have created a web of new economic and diplomatic links, from currency swaps to trade agreements to the new annual East Asian Summit”[v]. But, notwithstanding all these changes in Asia today there is a new arms race. As soon as the economies of the most important Asian states started to grow all the countries began to improve their arsenals. In other words, this behavior does not match well with the idea of a world where economies are just a target. It seems more that nations use good economic results in order to grow also from a military point of view and that then with these new forces they are able to guarantee their self-interests.

Which Interpretation — It is difficult in today’s world to give a correct answer on how to interpret international politics. According to our analysis it is difficult to accept — in the light of the provided examples — the school of liberalism as a trustful ideology in order to understand the international arena. The principles expressed by the school of realism have a more direct link with all the events that are currently happening in the world of international politics. The message provided by liberalism should be rather used as a tool to bring all the principal actors of the international arena to understand that their self-interests will bring in the long run to a zero-sum game. Conversely, all the ideas expressed by liberalists should be understood not as granted features but they can be constructed as targets to be achieved with sacrifice and hard work. And in this way self-interests that normally would create a zero-sum game can be tamed through the ideas of liberalism and be transformed and eventually generate a sort of win-win game. This should be the way to interpret the two schools of thought, which in this way could be reconciled in one organic structure.

What Role for the States? — What is interesting is — as it was underlined above — the presence of new actors in the international arena. It is difficult today to understand clearly what will be the role of the state in the next decades. It is probable that the presence of new actors in the international arena will erode part of the sovereignty of nation-states. With reference to this issue, the French thinker Jacques Attali[vi] offers us some considerations. He first imagines around 2035 a decline for the American empire and the creation of a polycentric world with nine important nations in the different continents: the U.S., Brazil, Mexico, China, India, Russia, the E.U., Egypt and Nigeria[vii]. Then, from this condition, he imagines for the following decades a world without nation-states where the only important reality will be the market. A sort of "marketization" of the world that he calls hyper-empire with no longer state entities, but where all the activities, once done by the public sector, will be now done privately and where citizens will be identified only as consumers.

It is difficult to say whether this situation may happen in the future. At the actual moment in the international arena it is only possible to identify:

- An increased number of actors — no more only nation- states.

- A world where next to the U.S. are emerging many regional powers of which the most important are China, India and Russia.

- A discredited role for the U.N., but also some very good results for other international organizations acting in other fields.

[i]

CARR, E., H., The Twenty Years’ Crisis 1919-1939,

Palgrave Macmillan Houndmills, Great Britain, 2001.

[ii]

BURCHILL, S., LINKLATER, A., Theories of

International Relations, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Great Britain,

2001, p.29.

[iii]

MORGENTHAU,

H., The Intellectual and Political Functions of Theory (1970), in J. Der Derian

(ed.), International Theory: Critical Investigations (Basingstoke, 1995).

[iv]

KURLANTZICK,

J. Asia’s Call for Arms, in Time Thursday

September 13 2007, http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1661456,00.html, accessed Monday September 17, 2007

[v] Ibidem.

[vi] ATTALI, J., Une

Bref Histoire de L’Avenir, Fayard, Paris, 2006.

[vii] Ibidem. Japan, Indonesia, Korea, Australia, Canada and South

Africa will have an important role but they will be in a secondary position

compared to the first nine countries.

Books

- ATTALI, J., Une Bref Histoire de L’Avenir, Fayard, Paris, 2006.

- BURCHILL, S., LINKLATER, A., Theories of International Relations, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Great Britain, 2001.

- CARR, E., H., The Twenty Years’ Crisis 1919-1939, Palgrave Macmillan Houndmills, Great Britain, 2001.

- HEWSON, M., SINCLAIR, T., J., Approaches to Global Governance Theory, State University of New York, New York, 1999.

- HOBSON, J., M., The State and International Relations, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000.

- KEGLEY, C. W. Junior, Controversies in International Relations Theory, Realism and the Neoliberal Challenge, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1995.

- MORGENTHAU, H., The Intellectual and Political Functions of Theory, 1970, in DER DERIAN, J. (ed.), International Theory: Critical Investigations, MacMillan, Basingstoke, 1995.

- VIOTTI, P., R., KAUPPI, M., V., International Relations Theory: Realism Pluralism, Globalism, and Beyond, Allyn and Bacon, Boston, 1997.

Articles

- DINGWERTH, K., PATTBERG, P., Global Governance as a Perspective on World Politics, in 12 Global Governance, 2006, pp. 185-203.

- KURLANTZICK, J., Asia’s Call for Arms, in Time Thursday September 13 2007 http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1661456,00.html, accessed on September 17, 2007.

- MURPHY, C., N., Global Governance: Poorly Done and Poorly Understood, in 76 International Affairs No 4, 2000, pp. 789-803.

- RUGGIE, J., G., International Regimes, Transactions, and Change: Embedded Liberalism in the Past-War Economic Order, in 36 International Organization No. 2, International Regimes, 1982, pp. 379-415.