ABSTRACT

The reduction in the

price of crude oil that has occurred over the last year and a half is taking

a relevant toll on the fiscal policies of the Middle Eastern producers. In

specific, the current troubles in the oil markets are compounded in Iraq proper

and in Iraqi Kurdistan (the Kurdistan Regional Government, the K.R.G.) by the

ISIS insurgency. As a result, the international oil companies (I.O.C.s)

producing crude oil in the K.R.G., among them Genel Energy, are experiencing

some financial difficulties (i.e., a substantial negative free cash flow) because the

K.R.G., in light of the mentioned problems, has not been able to establish a regular flow of payments in relation to

the produced oil.

INTRODUCTION

The reduction in the

price of crude oil that has occurred over the last year and a half is taking a

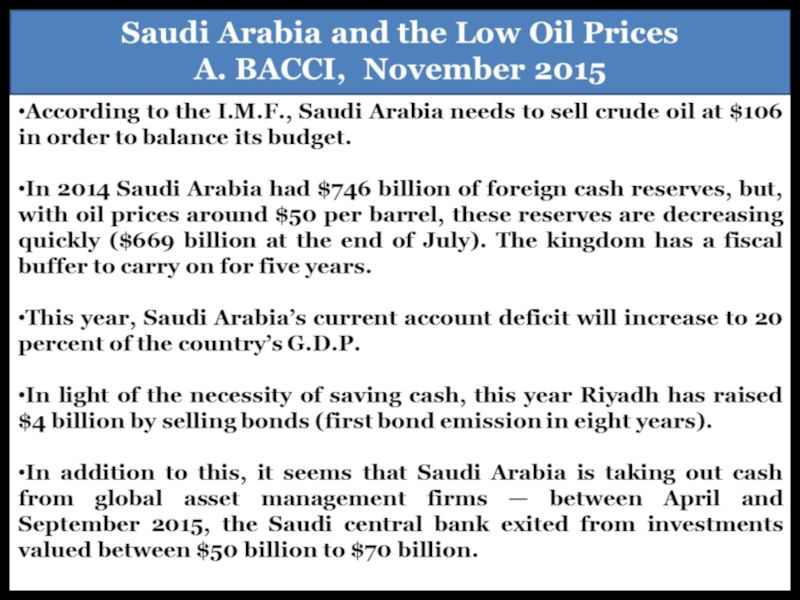

relevant toll on the fiscal policies of the Middle Eastern producers. A barrel

of oil in June 2014 cost around $110, while current prices stay close to $42 for W.T.I. and $45 for Brent. Notwithstanding some dissenting positions, the OPEC

members under the guidance of Saudi Arabia have decided not to curb their oil

production. OPEC's idea is to maintain its market share while trying to push

out of the market high-cost oil producers (for instance U.S. shale oil

producers). This policy was decided during the OPEC meeting of fall 2014 and is

still applied today. Indeed, in the Middle East the oil price decline has reduced the governments' spending power, which has been the engine of the

non-oil economy during the last years. Now, Middle Eastern countries have

fiscal balances severely affected by the current low oil prices. It's true that

some of these countries, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E., have accumulated consistent

financial buffers that may permit them to implement the necessary fiscal

adjustments in a more gradual manner. But, most of the countries in the region

are not able to balance their budgets when oil prices are under $60 a barrel.

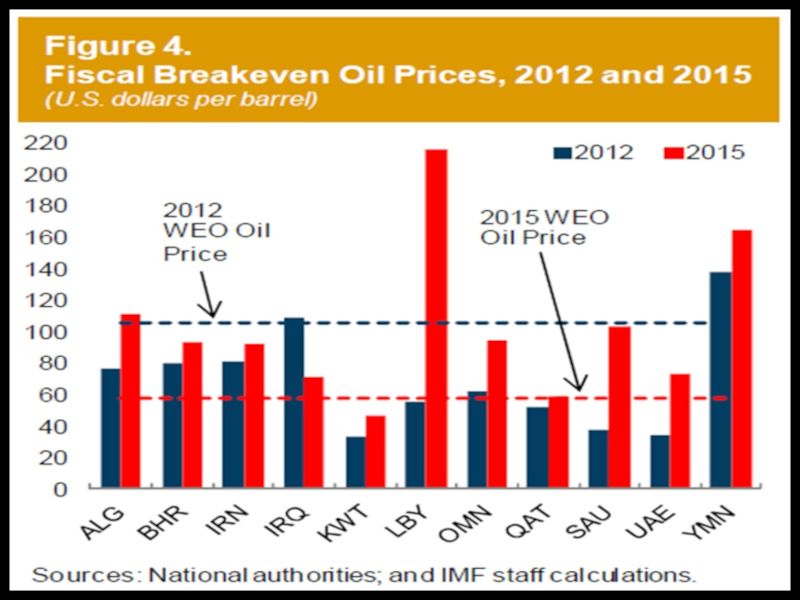

The figure below shows the fiscal break even oil prices according to the

International Monetary Fund (I.M.F.).

As a consequence of the fewer available economic resources and of the necessity of maintaining their current oil production, Middle Eastern oil producers are postponing the investments necessary to reverse natural field decline and to sustain production in the long term with new oilfields. For instance, Saudi Arabia, the U.A.E. and Qatar are delaying to 2016 non-essential maintenance work at oilfields; this work was planned for the fourth quarter of 2015. Maintenance work increases production in the long term, but in the short term it always reduces the output from the oilfields under maintenance and check; and, as explained above, right now OPEC wants to maintain its production, which is around 31.6 million barrels per day (bbl/d), in order to win its price war against high-cost oil producers. Similarly, oil majors are cutting spending and are shelving several new projects.

A SNAPSHOT OF IRAQ PROPER'S OIL PRODUCTION

The current troubles

in the oil markets are compounded in Iraq proper and in Iraqi Kurdistan (the Kurdistan Regional Government, the K.R.G.) by the ISIS insurgency. As a matter

of fact, ISIS still controls vast swaths of Iraqi territory, primarily the western

and northern parts of Iraq proper (For more information please see: BACCI, A., Iraqi Kurdistan's Occupation of Kirkuk Oil Field Will Deeply Affect the Iraqi Oil Sector, June, 2014). This insurgency, which is creating additional

fissures and cracks to that already shaky edifice that is the Iraqi state, has

a high human and economic cost for both Baghdad and Erbil. In this regard, the

Iraqi Oil Ministry has already issued a warning where it affirms that it will

reduce significantly spending reimbursement to independent energy

companies in 2016; this could inhibit maintenance and expansion of Iraq's

planned production goals.

At the world level Iraq proper is actually the fastest

source of oil-supply growth; Iraq is OPEC's second biggest producer after Saudi

Arabia. Iraq's output was around 4.2 million bbl/d in the third quarter of 2015,

while in September 2015 oil sales surpassed 3.052 million bbl/d. Later, October

2015 saw a sales reduction at 2.7 million bbl/d because of primarily bad

weather conditions during the last days of the month. It should be noted that

Iraq's 2015 federal budget envisaged an average sale price of $56 per barrel

from exports at an estimated rate of 3.3 million bbl/d (including oil from the

K.R.G. and the Kirkuk area under Kurdish control). These numbers are far from

real. For instance, October average sale price for Baghdad was $39, i.e., every

single day Baghdad lost $45.9 million (2.7 million bbl/d * ($56-$39)) in

comparison to the price written in the 2015 federal budget. It's evident that this

calculation is quite 'rough' and 'oversimplified', but it gives at least an

idea.

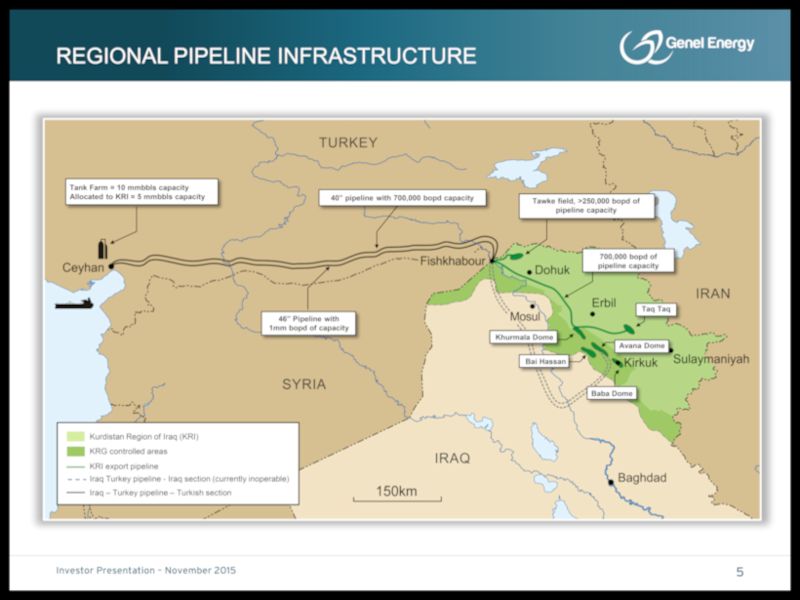

It's worth remembering that as a consequence of the dispute over export rights and budget payments between Erbil and Baghdad, shipments from Iraq's north via Ceyhan, in Turkey, by Iraq's State Oil Marketing Organization (SOMO) stopped in September. In practice, the K.R.G. stopped delivering Kirkuk oil to SOMO in Ceyhan. This means that since September Baghdad has been exporting oil only from fields located in southern Iraq, while Erbil has been exporting oil also from fields in northern Iraq (For more information please see: BACCI, A., Why Do I.O.C.s Have to Invest in Iraqi Kurdistan and/or Southern Iraq?, February 2015). Very realistically this outcome was expected despite the signature between Erbil and Baghdad in December 2014 of an agreement concerning the distribution of oil revenues in Iraq.

The December 2014 agreement specified that

Baghdad should have paid Erbil 17 percent of Iraq's national budget (in the

past years this 17 percent accounted for 95 percent of the K.R.G. revenues) as

specified in the Iraqi Constitution, while Erbil would have provided the

central government with 250,000 bbl/d of Kurdish oil at Ceyhan for export. In

addition, the K.R.G. would have also exported via the newly built Kurdish

pipeline 300,000 bbl/d of oil extracted from the oil fields of the area around

Kirkuk (Bai Hassan, Dubis and Havana fields). These oil fields are under

federal jurisdiction, but they are currently under Kurdish control. The

Kurdistan region’s share of Iraq’s 119.5 trillion dinar budget for 2015 amounted

to 14.8 trillion dinars ($13.3 billion), based on the 17 percent share to which

Erbil was constitutionally entitled; this means that Erbil was expecting from

Baghdad a little more than $1 billion monthly.

At the time of the signature, in December 2014,

under Iraq's dire economic, political, legal and social conditions the

agreement appeared as probably the best solution for the concerned parties. In

other words, this deal was immediately understood as a temporary agreement that

was not supposed to solve completely the friction points between Erbil and

Baghdad, but that, at least, could have permitted Iraqi Kurdistan and Iraq

proper to improve their coffers and, thanks to this, to wage with better means

a war against their common enemy, which was — and sadly is today — the Islamic

State. For Baghdad this deal was useful because through the newly built Kurdish

oil infrastructure (from Kirkuk to the K.R.G. and then from the K.R.G. to the

border with Turkey where two Kurdish pipelines enters the Kirkuk-Ceyhan

pipeline) it was again able to export oil from Kirkuk's fields. In fact, since

March 2014 oil from these fields had not being exported anymore because the

Iraqi leg of the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline — the only means of transportation —

had been sabotaged by terrorist attacks (For more information please see: BACCI, A., The Iraqi-Kurdish Oil Deal, December 2014).

THE

FAILURE OF THE DECEMBER 2014 AGREEMENT

The problem is that since December 2014 until

now this agreement has never been correctly implemented. For the first three

months of 2015 Erbil was in the impossibility of exporting the established

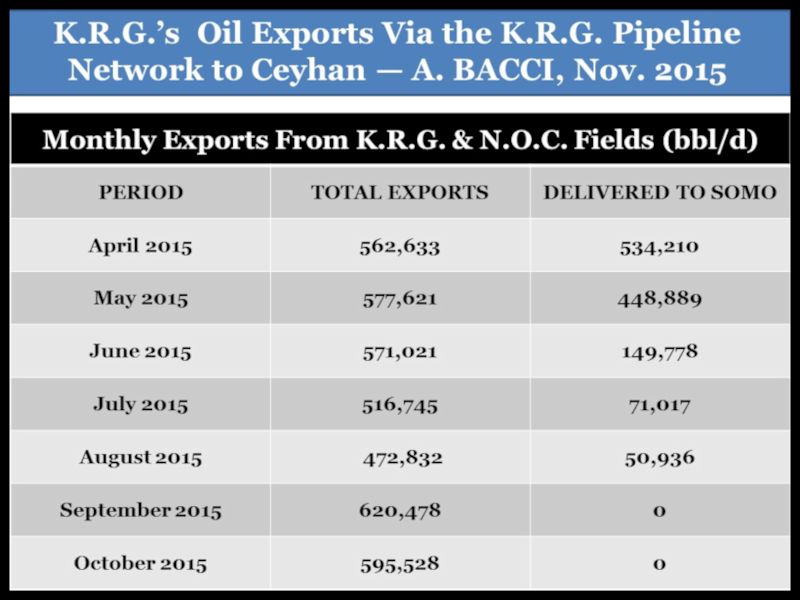

quantities and, consequently, Baghdad paid less than agreed. Then, in April Kurdish

exports from the K.R.G. and from the Kirkuk area reached 562,000 bbl/d and

Erbil delivered to SOMO 534,210

bbl/d. In May, Kurdish exports totaled 577,621 bbl/d of which 448,889 bbl/d were

delivered to SOMO. At the same time, Baghdad's payments did not proportionally

increase in order to reflect the increased quantities of oil shipped by Erbil. In

brief, during the first five months of 2015, Erbil received only a third of its

budget entitlement.

Later, on June 24, the K.R.G. (with the

approval of the five political parties in the coalition government) decided to start

selling oil independently of SOMO. During the following three months, Erbil

continued to deliver SOMO reduced quantities of crude oil, but in September it

stopped completely. The slide below clarifies the K.R.G. exports of crude

oil from April to October 2015.

The K.R.G. is now able to export from the K.R.G. and the Kirkuk area oilfields via its new infrastructure around 600,000 bbl/d (in October precisely 595,528 bbl/d, of which 439,073 bbl/d from the K.R.G. oilfields and 156,455 from the Kirkuk area oilfields). Erbil is committed to exporting 900,000 bbl/d by the end of 2015.

For the K.R.G. direct exports sales are the consequential

conclusion of a financial crisis that started early in 2014 when then Prime

Minister Nouri al-Maliki of Iraq stopped budget payments to the K.R.G. because

the latter was trying to sell its crude oil independently of Baghdad's

authorization. The war against ISIS and the influx in the K.R.G. of more than

1.8 million of displaced Iraqis and Syrians added to the already present

financial problems. Many Kurdish companies bankrupted and consequently

thousands of people lost their jobs; in recent months protests over the staff

and workers’ salaries delay have taken place across Iraqi Kurdistan. In October, Head of Foreign Relations Department Falah Mustafa Bakir told the U.N. General Assembly that Erbil has a delay of three months in paying out the salaries to civil servants (among them the Peshmerga forces battling against ISIS). In practice,

in light of the economic crisis, direct exports were the only available

alternative path. Minister of Natural Resources Ashti Hawrami had supported

direct sales immediately after the initial misunderstanding with Baghdad

following the December 2014 agreement. The revenue gained from direct sales is

still below Iraqi Kurdistan's 17 percent share of the national budget, but it's

indeed higher than the economic resources transferred by Baghdad on a monthly

basis. This is also due to the K.R.G. difficulty in finding purchasers for its

crude oil. In fact, especially last year, many buyers, despite their interest,

did not decide to purchase Kurdish oil for fear of retaliation on the part of

Baghdad (for instance, suing the companies that were lifting oil via the K.R.G.

pipeline). For this fear, some of the cargoes loaded with Kurdish oil departing

from Ceyhan delivered their cargo via ship-to-ship transfer after having turned

off their satellite transponders (For more information please see: BACCI, A., The Emergence of the K.R.G. as an Oil-Exporting Area, August 2014). Now, probably because of the internal chaos,

Baghdad is slightly less aggressive with reference to Erbil's independent exports.

Today it's sure that some Kurdish cargoes go from Ceyhan to refineries in

Israel, Italy, France and that Kurdish oil is traded by Vitoil and Trafigura,

which are among the world's biggest oil traders. At the end of August the

K.R.G. affirmed that it had received more than $1.5 billion in oil payments

during the previous two months. In other words, some money started to flow

toward the K.R.G. although still with some difficulties linked to banking

procedures.

In August, the Ministry of Natural Resources of the K.R.G. announced that from the following month, September 2015, the K.R.G.would allocate part of the revenues coming from its direct crude oil sales tothe I.O.C.s currently 'producing' oil in Iraqi Kurdistan.

THE

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN OIL PRODUCING I.O.C.s AND OIL EXPLORING I.O.C.s

These companies are presently experiencing

relevant cash shortfalls. It's important to underline the word 'producing'. In

fact, in the K.R.G. there are approximately 50 I.O.C.s that are doing petroleum

operations, but most of them are only in the exploration phase. These companies

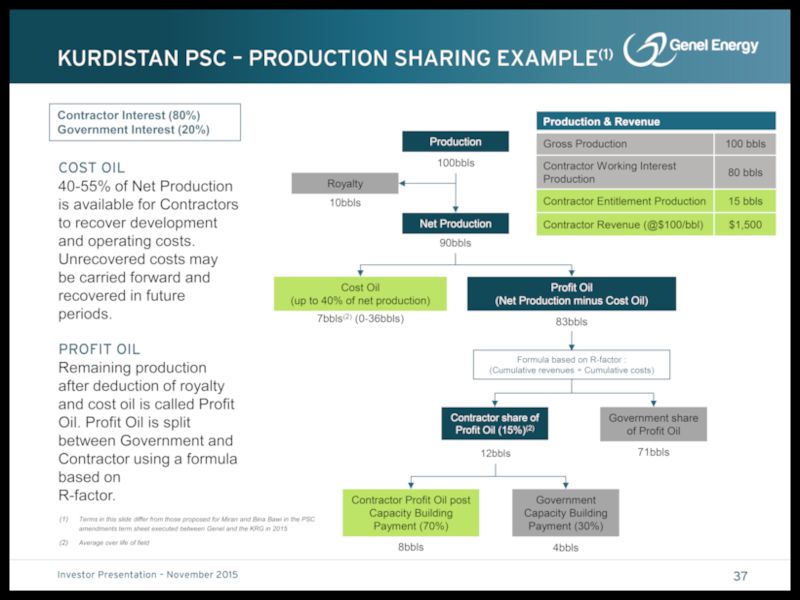

(producing companies and exploring companies as well) have all signed

production sharing contracts with the K.R.G (in general there is 10 percent

royalty and a 40 percent cost recovery limit for crude oil and associated

natural gas). This means that company during the exploration phase will not be

reimbursed for the incurred costs; things of course change after a first

commercial declaration — it's a very standard P.S.C.

Among the major I.O.C.s only for the moment active in the exploration phase there are U.S. ExxonMobil and Chevron, and France's Total; it goes by itself that these majors have quite larger financial resources than the medium-sized petroleum companies (in any case they are not wildcatters) already in the production phase in Iraqi Kurdistan (For more information please see: BACCI, A., Chevron and Total Continue Investing in the K.R.G. A Brief Analysis of Baghdad's T.S.C.s vs. Erbil's P.S.C.s, June 2013). These major companies retain certain flexibility because in the future according to the political, legal, and economic conditions affecting Iraqi Kurdistan they could implement three different strategies:

Among the major I.O.C.s only for the moment active in the exploration phase there are U.S. ExxonMobil and Chevron, and France's Total; it goes by itself that these majors have quite larger financial resources than the medium-sized petroleum companies (in any case they are not wildcatters) already in the production phase in Iraqi Kurdistan (For more information please see: BACCI, A., Chevron and Total Continue Investing in the K.R.G. A Brief Analysis of Baghdad's T.S.C.s vs. Erbil's P.S.C.s, June 2013). These major companies retain certain flexibility because in the future according to the political, legal, and economic conditions affecting Iraqi Kurdistan they could implement three different strategies:

- STRATEGY A: Go ahead with the production phase if the exploration is successful.

- STRATEGY B: Shut down their operations if exploration is not successful and/or if the political, legal and economic conditions affecting Iraqi Kurdistan do not permit them to carry out a profitable petroleum operation.

- STRATEGY C: Enter in one of the projects already producing oil in the K.R.G.

Of course, Strategy A could also be developed

together with Strategy C, while the latter could be developed together with Strategy B.

Instead, things are completely different for the

companies already producing oil. In this regard, the K.R.G. recognizes that

since May 2014 these companies have received hardly any payments for their

Iraqi Kurdistan operations. And, since the beginning of the exports a couple of

years ago as of August 2015 these companies received only $100 million despite

the revenues were in the order of billions of dollars. Erbil owes the producing

I.O.C.s more than $1 billion.

WHAT

ARE THE MAJOR K.R.G. OILFIELDS OPERATED BY I.O.C.s?

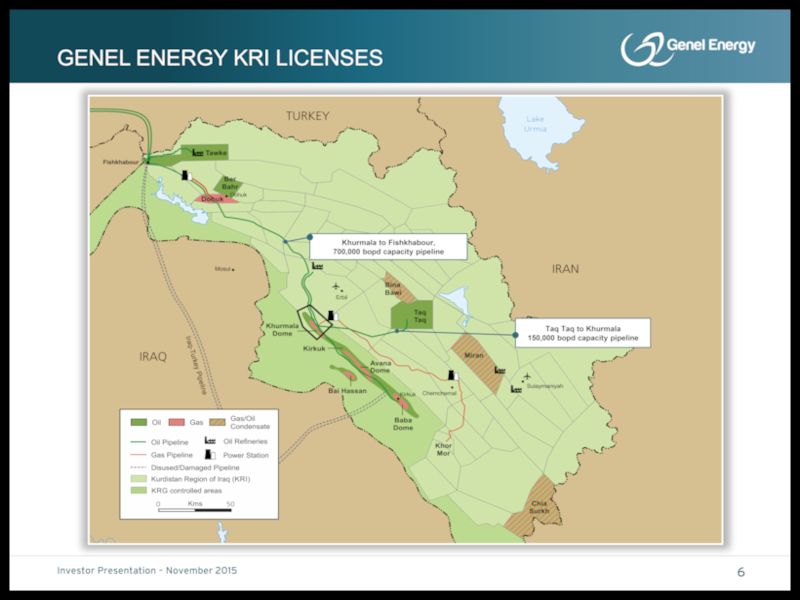

Apart from the Khurmala Dome (the northern tip

of Kirkuk), which has a production capacity of 110,000 bbl/d (Energy Information Administration, E.I.A., January 2015), but that it's locally

developed by KAR Group, a Kurdish privately owned group, in the K.R.G. there

are three main oil producing fields under the operatorship. They are:

- TAWKE (Production 152,000 bbl/d) Norway's D.N.O. is the operator (55 percent) and the remaining partners are Anglo-Turkish Genel Energy (25 percent) and the K.R.G. (20 percent)

- TAQ TAQ (Production 85,000 bbl/d) Genel Energy is the operator (44 percent), and the remaining partners are China's Sinopec (36 percent) and the K.R.G. (20 percent).

- SHAIKAN (Production 40,000 bbl/d) U.K. Gulf Keystone is the operator (75 percent), and the remaining partners are Kalegran Ltd. (100 percent subsidiary of M.O.L. Hungarian Oil and Gas Plc. with 20 percent) and Texas Keystone Inc. (5 percent).

For more information about the K.R.G. oil sector please see: BACCI, A., An Analysis of the K.R.G. Oil Sector According to the Five Forces Framework, March 2015.

Finally, in September 2015, the Ministry of

Natural Resources authorized a $75-million tranche of regular payment to the

I.O.C.s. The tranche was divided as follows:

- $30 million to Taq Taq Operating Company (Genel Energy and Sinopec)

- $30 million to D.N.O. in relation to Tawke

- $15 million to Gulf Keystone in relation to Shaikan

These payments are useful, but they are really a

trickle in comparison to what the companies are owed by the K.R.G.

THE

CASH PROBLEM

These producing companies are cash-strapped, and

it will be impossible for them to continue exporting at the current levels

without a stable flow of payments. In addition to covering expenses, CASH is of

paramount importance in order to plan for further investments in the oil fields

boosting the K.R.G. production. In other words, in the K.R.G. oil sector, it's

possible to understand a basic financial concept, i.e., PROFIT and CASH are two

different elements, both of which need to be present in order to have a healthy

company. Financial books are full of stories of profitable companies that have

been forced to bankrupt because they simply ran out of cash. And right now the

balance sheets of the companies producing in the K.R.G. are full of ACCOUNTS

RECEIVABLE, which are promises yet to be collected. Only once collected these

promises become real cash for the I.O.C.s.

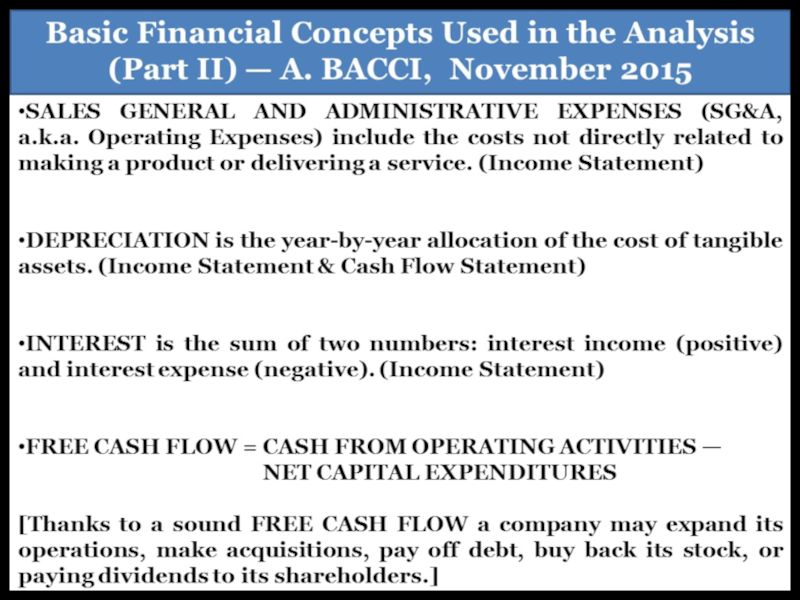

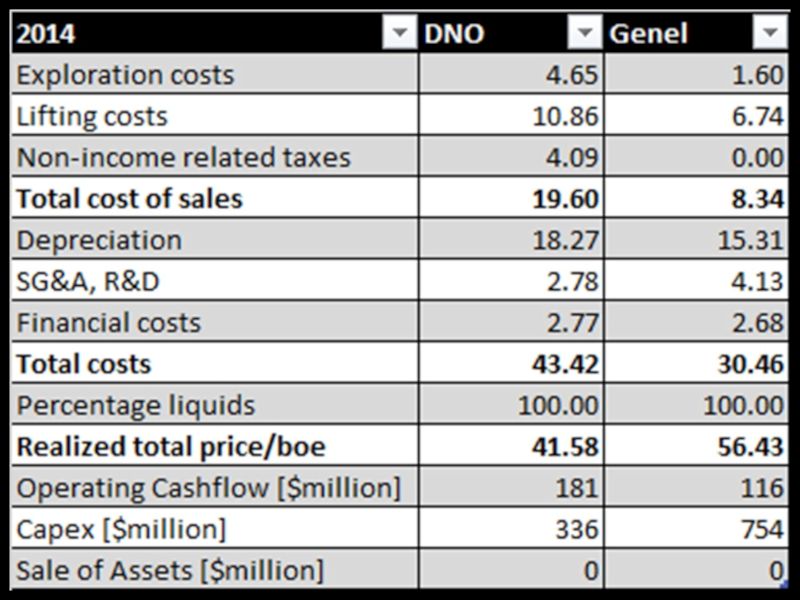

What is happening in Iraqi Kurdistan explains us that the problem does not lay in the production phase; COGS (COST OF GOODS SOLD, which in the oil business may be divided in EXPLORATION COSTS, LIFTING COSTS and NON-INCOME RELATED TAXES) are really competitive in the K.R.G. For instance, Genel has overall COGS in the order of less than $10. Of course, to get FINAL COSTS we need to add back SG&A (SALES, GENERAL and ADMINISTRATIVE EXPENSES), DEPRECIATION and INTERESTS, but the basic idea is that the pure production costs in the K.R.G. are very (very) competitive at the world level. And the profit any petroleum company is able to do is primarily linked to its COGS. So, in the K.R.G. while oil production is very cheap, then it's difficult to sell the oil and to receive the related payments. If there weren't political, legal and security difficulties, which partially eat away the COGS advantage, the main producing I.O.C.s would already be the big names of the petroleum business. The slide below shows information concerning the cost of producing a barrel of crude oil in the K.R.G.

|

| Source: AUBLINGER, C., How Much Does It Cost to Produce 1 Barrel of Oil in Kurdistan (DNO and Genel in 2014)?, May 2015 |

Current production in the K.R.G. is already too big in order to be sold locally (with discounted prices around $30; in the last six months some I.O.C.s have increased their local sales because they have been unable to get a steady flow of payments from Erbil with reference to the pipeline exports). Similarly, it's not possible to use trucks for such a big quantity: It's very expensive and also quite complex from an infrastructural point of view. In other words, with a production of already more than 500,000 bbl/d the only economically viable way of exporting crude oil is for Erbil via pipeline.

So cash is the real problem for the

I.O.C.s already producing crude oil in the K.R.G. How long will these I.O.C.s

be able to continue producing crude oil without a steady flow of cash? They

have already borrowed money (with bond emissions) and could probably do this

again, but is it really viable in the medium to long term? Any business company

wants profit and wants to transform profit into cash in reasonable timeframe. Publicly

traded companies may deviate from such a behavior only temporarily when they

have other goals that can be better served by carrying out unprofitable

operations — for instance, in Kuwait, I.O.C.s have signed Enhanced Technical

Service Agreements (E.T.S.A.s) mainly because they wanted a working relation

with K.O.C. (Kuwait Oil Company), so that, if Kuwait in the future proposes

better contracts, the companies will have more chances of signing the new and

improved petroleum contracts because they are already working in Kuwait (For more information please see: BACCI, A., Kuwait's Oil and Gas Contractual Framework and the Development of a Modern Natural Gas Industry, December 2011). In the

same way, when any national oil company (N.O.C.) deviates from profit and cash,

in generally, it does so for political reasons. But it's also true that in the

last decades many N.O.C.s have really started to act more in a

business-oriented manner.

GENEL

ENERGY AND CASH

Let's focus our attention on Genel

Energy, which is the largest independent oil producer and the largest holder of

reserves and resources in the K.R.G.

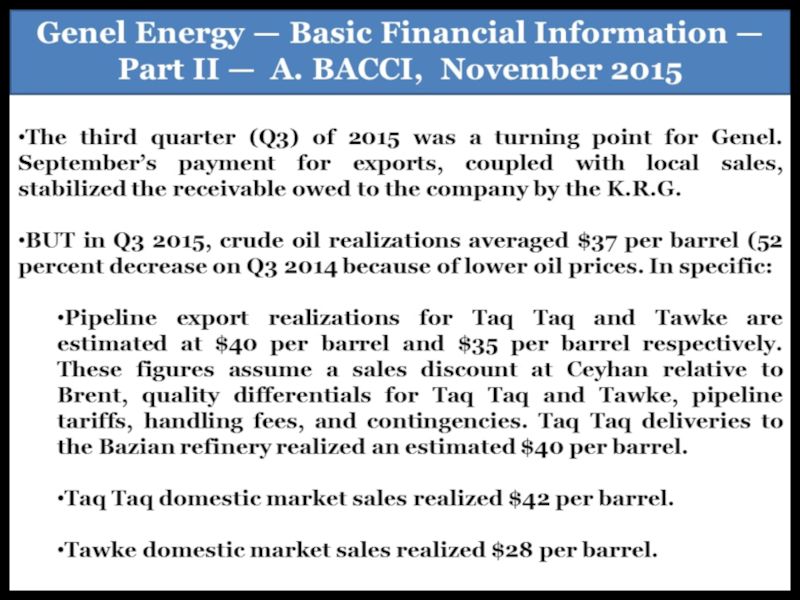

Checking the data released by Genel Energy in August in relation to the results of the first six months of 2015 and in October in relation to the trading and operations update demonstrates the paramount importance of a steady flow of payments by Erbil.

Checking the data released by Genel Energy in August in relation to the results of the first six months of 2015 and in October in relation to the trading and operations update demonstrates the paramount importance of a steady flow of payments by Erbil.

The pictures below show the condensed consolidated cash flow statements and the income statements for the last years.

Genel Energy has petroleum operations in the K.R.G. and in four areas in Africa (Somaliland, Ethiopia, Morocco and Ivory Coast). The African operations are still in the exploration phase, so they do not generate revenues but only relevant costs. For instance, in the fiscal year 2014, Genel Energy had exploration expenses of $476.8 million, which originated completely from the African operations — while exploration expenses related to the K.R.G. were zero in that year; of course not all the years are the same. But, this means that for the time being, Genel Energy is able to generate its revenues (and consequently, its profit and its cash) only from its Kurdish operations. If Erbil is unable to pay its dues to Genel Energy, it's quite probable that the company will have to sustain some financial difficulties.

In all of the considered periods the

balance between CASH FLOWS FROM OPERATING ACTIVITIES and CASH FLOWS FROM

INVESTING ACTIVITIES was always negative. In addition, it's worth noting that

in all of the periods the company obtained relevant proceeds thanks to bond

emissions, the last of which was done in March 2015 for a value of $230 million

— currently Genel Energy has a $730 million debt (7.5%

senior unsecured bond with 2019 maturity).

The other two producing I.O.C.s, D.N.O. and Gulf

Keystone, are similarly experiencing some financial difficulties — in June 2015 the K.R.G. owed D.N.O. almost $700 million and Gulf Keystone $283 million. In

particular, Gulf Keystone has a more complex situation, and it could be

interested in attracting a farm-in partner or a strategic investor to progress

with its Shaikan investment. Despite Gulf Keystone economic troubles, proved and probable

reserves at Shaikan have recently been increased to 639 million barrels gross

from 299 million barrels gross. So, one more time it's possible to fathom the

important business truth present in the expression "Cash is king".