The article “Lebanon Launches Its Offshore Oil and Gas Sector” has been initially published by Oilpro, a professional network for the oil and gas professionals

June 28, 2017

LONDON — I want to start

this analysis concerning Lebanon by saying that I wish Lebanon, a beautiful

country where I lived for three full years between 2012 and 2015, all the best possible

luck in regard to its petroleum (oil and gas) sector development. In fact,

after years of postponements, Lebanon is finally kickstarting its offshore oil

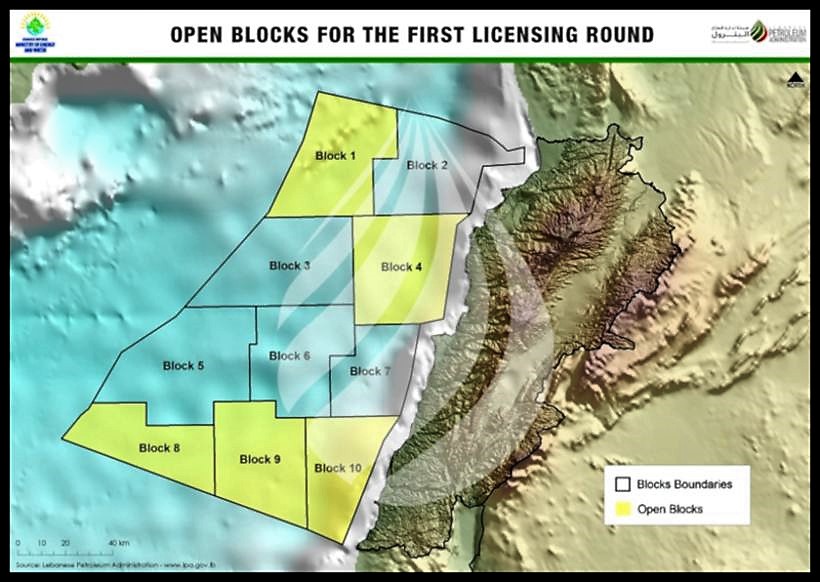

and gas (O&G) industry. On January 4, 2017, the government approved two

decrees, which were necessary to go ahead with the licensing procedure. Decree

No. 42 defines the geographical parameters of the blocks in which Lebanon’s

economic exclusive zone (E.E.Z., 22,700 sq. kilometers) is divided; Decree No. 43

sets out the tender protocol (T.P.) and the model exploration and production

agreement (E.P.A.) to be entered with the bidding companies. A few weeks later,

on January 26, 2017, Minister of Energy and Water Cesar Abi Khalil declared

that blocks 1, 4, 8, 9, and 10, out of 10 overall blocks, would be open for

bidding during the first offshore licensing round.

Then a pre-qualification

round, a second pre-qualification round to be more precise, was held between

February 2, 20117 and March 31, 2017; according to this second

pre-qualification round, 8 new companies qualified: 1 operator (India’s O.N.G.C.

Videsh Limited) and 7 non-operators. Previously, in 2013, 46 companies had

qualified via the first pre-qualification round—in specific, 12 of them

qualified as operators (among them U.S. Chevron and Exxon Mobil, U.K. Shell, and

France’s Total). But then, at that time, the tender process stopped abruptly.

In fact, the government had never passed the decrees necessary to have a

licensing round until January 2017.

In sum, because not all

the 46 companies that pre-qualified in 2013 will be part of the licensing

round, there are now 51 companies that have pre-qualified and should be willing

to take part in the tender submitting bids in relation to the open blocks on

September 15, 2017. After that day, the Lebanese Petroleum Administration (L.P.A.)

will assess the received applications and send a report to the cabinet, which

will decide by November 15 which companies will win the tender.

|

Attracting Exploration Investment by

Ensuring Progressive Fiscal Regime — Source: Wissam Zahabi

|

Initial estimates tell

that buried under the Lebanese seabed there could be 30 trillion cubic feet

(around 850 billion cubic meters) of natural gas and 660 million barrels of

oil. Of course, until the companies that will sign a production sharing

contract (P.S.C.) with the Lebanese government start their exploration phase,

it’s impossible to confirm whether these initial estimates are correct. In

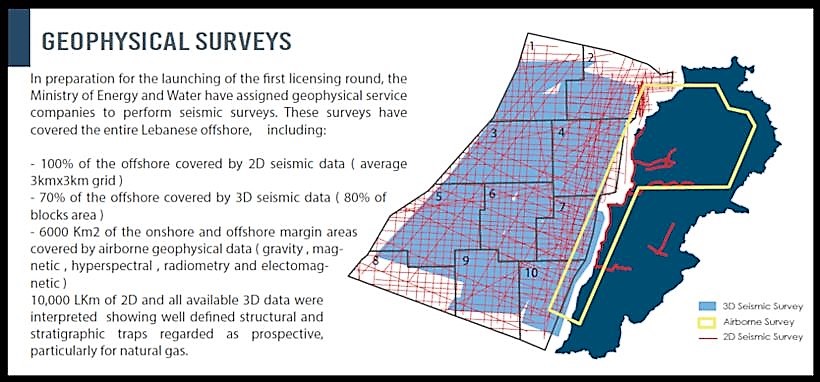

preparation for the launching of the first licensing round, some years ago, the

Ministry of Energy and Water had assigned geophysical service companies to

perform seismic activities. These surveys covered the entirety of Lebanon’s

offshore territory. In particular, 100 percent of the offshore was covered by

2D seismic data and 70 percent of the offshore was covered by 3D seismic data.

Thanks to this activity, data related to 10,000 kilometers of 2D surveys and

all the available 3D data, once interpreted, showed well defined structural and

stratigraphic traps regarded as prospective, especially for natural gas.

|

| Geophysical Surveys — Source: Lebanese Petroleum Administration |

In other words, until

companies start drilling, there is no certainty of Lebanese O&G reserves,

but 2D and 3D mapping and the recent natural gas discoveries in the E.E.Z.s of

Cyprus, Egypt, and Israel give the Lebanese government hope that also Lebanon’s

E.E.Z. could be rich in O&G—in 2010, the United States Geological Survey

estimated that there could be up to an additional 122 trillion cubic feet of

undiscovered natural gas in the Levant Basin, with also 1.7 billion barrels of

recoverable oil. This means that for an international oil company (I.O.C.),

when evaluating whether to invest in Lebanon, the risk doesn’t lie too much in

geological problems but in geopolitical problems. In fact, because we’re

talking of offshore operations, if on the one hand it’s true that finding and

development (F&D) costs won’t be low, on the other hand they should not be too

different from other offshore operations across the globe. For sure, if the

price of a barrel of oil went down to $20 a barrel—a possibility that cannot be

completely ruled out—there would be great difficulties in achieving breakeven.

So, the real problem for

an investor is the geopolitical risk, which in Lebanon may be split into two main

components: Lebanon’s very complex and dysfunctional internal politics and

Lebanon’s difficult relationships with its neighbors.

With reference to the

first component, it’s difficult to look to Lebanese politics with trust and

hope. In fact, Lebanon’s politics is based on religious divisions (a confessionalism

including 18 recognized religious sects). In practice, the highest offices are

reserved to representatives from certain religious communities. For example,

the president of the republic must be a Christian Maronite, the prime minister

a Sunni, and the speaker of the Parliament a Shia. Similarly, seats in the

Parliament are confessionally distributed but elected by universal suffrage.

Each religious community has an allotted number of seats in Parliament,

although all candidates in a particular constituency must receive a plurality

of the total vote, which includes followers of all confessions. Indeed, it’s a

complicated system, but, it’s the system that was introduced with the National

Pact of 1943 (slightly changed in 1990 after the end of the Lebanese Civil War).

The logic of this system is that it should be able to reduce the possibility of

armed violence between the different components of Lebanon’s society, but at

the same time its result is a big drag on the speed and meritocracy of

Lebanon’s politics. Also, the members of the L.P.A. have been selected

according to sectarian lines.

Doing politics in Lebanon

is quite difficult. Among the main political problems that Lebanon has recently

experienced in the last years five years—and I just go by memory—there are the

following issues

- Absence of the president of the republic for more than two years (29 months)

- Absence of a continuous supply of electricity

- Acts of violence across the country, Beirut included

- A high level of corruption at all levels of Lebanon’s society

- A high public debt at 146 percent of the country's G.D.P. in 2016

- Garbage crisis and related environmental issues

- More than 1 million of Syrian refugees, but the number could be close to 2 million

- Parliamentary elections, to be held in 2013, postponed until at least mid-2018

- Poverty with around 28 percent of the population living under the poverty line

- Savage privatization of public land across the country

With reference to the

second component, Lebanon and its southern neighbor, Israel, are still

technically at war. Moreover, to add an additional layer of complexity, there

is an 854-square-kilometer wedge of sea between the two countries claimed by

both Beirut and Tel Aviv. In the last years, the U.S. has tried to figure out a

solution, or at least to avoid that this dispute could escalate into something

more dangerous. In this regard, the U.S. has discouraged Israel and Lebanon

from conducting O&G operations in the disputed wedge of water.

|

| The Disputed Wedge of Water — Source: Menas Associates |

In Israel, Noble Energy, a

U.S. energy company quite active in Israel, and Israel’s Delek Group held the

license for block Alon D, which stretches into the disputed area. This license

expired in March 2016. Several reports have explained that the Israeli

government has prevented drilling in the license area Alon D. Another

controversy with Israel was linked to the discovery of the Tanin and Karish gas

fields by Noble Energy in 2012 and 2013. These fields are located in

Israeli-licensed areas Alon A and Alon C. And Alon C is only 4 kilometers away

from Lebanon’s block 8 and 9 kilometers from block 9. Tension between Israel

and Lebanon when Noble started drilling in the Karish field, which according to

Noble Energy is 10.6 kilometers from Lebanon’s block 9, while according to

Lebanon is just 4 kilometers away from the block. As a consequence, Lebanon’s

government immediately voiced its concern regarding Karish field operations

because these could affect the Lebanese gas reserves, either by drilling in a

contiguous gas resource, or through horizontal drilling—Nabih Berri, the speaker of the Lebanese Parliament strongly

voiced its concerns regarding the disputed offshore territory. Today, after a series

of business transactions, the license to the Karish and Tanin fields is held by

the Greek company Energean Oil & Gas.

|

| Israel's Offshore Fields — Source: Offshore Energy Today |

But now, Lebanon’s first

offshore licensing round might create trouble. In fact, 3 blocks (block 8, 9,

and 10) out of 5 of the blocks to be licensed cover the length of the offshore

border between Israel and Lebanon, i.e., they include the disputed wedge. Why

that? In March, at Eastern Mediterranean Gas Conference (E.M.G.C.) 2017 in

Cyprus, Mr. Wissam Chbat, chairman and head of geology and geophysics of L.P.A.

explained that

- Block 1 has high-to-moderate hydrocarbon potential, with gas, possible condensate, and oil expected to be discovered

- Block 4 has moderate potential for gas, oil, and possible condensate

- Block 8 has high potential for gas and some condensate

- Block 9 has very high potential for gas, condensate, and oil

- Block 10 has very high potential for oil, condensate, and some gas

|

Open Blocks for the First Licensing Round —

Source: Lebanese Petroleum Administration

|

The government justification

for the green light to proceed with block 8,9, and 10 is that they have a high

potential. And in order to lure I.O.C.s’ interest in Lebanon’s offshore, it’s

better to offer immediately the most promising areas, especially in the present

environment of low oil prices. The idea is that it’s always better to start

with the right foot.

In addition, as mentioned

above, with reference to the three southern blocks, in the past, several times

Lebanese politicians raised the issue that Israel, which is quite ahead of

Lebanon in its offshore operations, via infrastructure located in its own

E.E.Z. could extract natural gas located in Lebanon’s E.E.Z. These fears could be

considered another justification to immediately put under a license those three

blocks. Moreover, it’s worth mentioning that Lebanon and Syria didn’t complete

the demarcation of their land and maritime borders either—Lebanon’s E.E.Z.’s

northern border and Syria’s E.E.Z.’s southern border. And now demarcating

maritime borders with Syria will probably be impossible until the end of the

conflict in Syria.

One initial consideration

is that Lebanon should have already begun the development of its petroleum

sector. Indeed, if the licensing phase had been completed in 2013, it would

have been better for the coffers of Lebanon’s Treasury. In 2013, Brent crude

prices averaged more than $100 a barrel. It’s true that petroleum operations,

if successful, could span at least three decades, which means that an I.O.C.

will always experience over the course of a specific project high oil prices as

well as low oil prices, but it’s also true that when a government organizes a

commodity licensing round, it’s much better if the price of the concerned

commodity is quite high. The only real advantage that Lebanon could have right now

is the low costs of oil services. Timing is not so good for Lebanon as it was

four years ago. Instead, in the eastern Mediterranean region both Cyprus, Egypt

and Israel are quite ahead with their projects.

In 2009, Noble

Energy announced the discovery of the Tamar field (280 billion cubic meters of

natural gas) in the Israeli E.E.Z. Then, still Noble Energy announced in 2010

the discovery of the Leviathan field (620 billion cubic meters) in the Israeli

E.E.Z. and in 2011 of the Aphrodite field (140 billion cubic meters) in the

Cypriot E.E.Z. Last but not least, in 2015, Italy’s E.N.I. announced the

discovery of the giant Zohr field (850 billion cubic meters) in the Egyptian

E.E.Z. These three countries are much ahead in their projects than Lebanon is. In fact,

- In Israel, natural gas is already extracted. The Tamar field was quickly developed and early 2013 it became operational supplying Israel with 7.5 Bcm per year; the Leviathan field’s Phase 1A will produce 12 Bcm per year starting in 2019.

- In Cyprus, thanks to three licensing rounds (in 2007, 2012, and 2016) block 12 (Noble Energy, Delek, and Shell), 2 (E.N.I. and Korea’s Kogas), 3 (E.N.I. and Kogas), 9 (E.N.I. and Kogas), 11 (Total and E.N.I.), 6 (Total and E.N.I.), 8 (E.N.I.), and 10 (Exxon Mobil/Qatar Petroleum) have been awarded.

- In Egypt, E.N.I. will start producing from Zohr in the 4th quarter of 2017—E.N.I. is the operator while British Petroleum has a 10-percent stake and Russia’s Rosneft a 30-percent stake. It’s possible that Zohr will be the first of a series of discoveries in the area. BP is proceeding with its development of West Nile Delta project, which could produce 12 Bcm, per year starting in 2017.

All this said, despite a

not-so-perfect timing and despite internal and external problems, Lebanon has probably

to try to develop its offshore resources. When I.O.C.s and a country sign a

petroleum contract, let’s say a P.S.C., they could arrive at the signature

starting from distinct positions, but when they sign, they have, hopefully,

found an agreement satisfying both parties. There is a caveat: under the

current low oil prices, I.O.C.s may find several different investment

opportunities; if a company doesn’t see an investment opportunity as

sufficiently profitable, it can easily switch to drilling in other localities. Instead,

a country doesn’t have the same privilege. Oil and gas deposits are fixed in a

specific place. In brief, a country has to do with what it has.

Indeed, a country has to

maximize its profits, but it has also to do a reality check. And, in the case

of Lebanon, this reality check may be done with an eye to the amount of dollars

that every year Lebanon must use to satisfy its energy requirements. In 2013, a

year with high oil prices, Lebanon imported oil and derivatives for an amount

of $5.11 billion, i.e., 11.4 percent of its G.D.P. Moving to 2016, a year of

low oil prices, there was an 8.20 percent yearly rise in value of oil imports

to $3.72 billion, which is equal to 98.21 percent of mineral products’ import

value. These numbers would probably be a sufficient reason for Lebanon to try

to develop its hydrocarbons sector. In fact, in addition to spending less

money, by developing its own offshore natural gas deposits, Lebanon could start

using natural gas rather than oil to produce electricity with many

environmental benefits, give its citizens and industrial sector a continuous

supply of electricity, permit its industrial sector to gain competitiveness in

pricing and exports, and increase its energy security. On top of these improvements,

Lebanese politicians, who are always overoptimistic, already envisage the

possibility of creating new industries like petrochemicals—this idea is very

premature.

Until now, citizens and large-scale

manufacturers have relied on their own electricity generators to ensure

uninterrupted electricity supply—in some parts of the country there is no

electricity for 18 hours a day, while at the same time current expenditures for

Electricité du Liban, the public body controlling 90 percent of the activities

of production, transportation and distribution of electricity in the country, are

still the third most important point in the budget after debt service and

public wages. Losses from intermittent energy supply and the utilization of

private generators have translated into a considerable loss of competitiveness

of Lebanese products on global markets. According to the Association of

Lebanese Industrialists, the average energy factor cost is 5.7 percent of the

companies’ selling price, but this cost is as high as 35 percent of the selling

cost for energy intensive industries like manufacturing.

By developing its offshore

natural resources, Lebanon could increase its overall energy security in order

not to repeat the problem Lebanon is currently facing with its two natural gas

power plants. In fact, presently Lebanon has already two combined cycle gas

turbines (C.C.G.T.s), Zahrani (460 MW) and Deir Ammar (460 MW), in operation

but they are not working properly because they use fuel oil and not natural

gas, which, in light of external political and economic circumstances, is not

currently exported to Lebanon.

Corruption is a huge

problem. Transparency International, a global civil society organization, in

its corruption perceptions index ranked Lebanon 136 out of 176 countries in

2016. And the idea of getting rid of corruption is probably just wishful

thinking. Think of Angola, which is a good case in point. From 2002 to 2015,

this country’s exports totaled almost $600 billion, nearly all of it from oil.

According to the Catholic University of Angola’s Center for Studies and

Scientific Research, oil revenue brought the government coffers $315 billion.

At the same time $28 billion from government budgets remained unaccounted for

and up to 35 percent of the money spent on road construction vanished. And in

relation to Lebanon, it’s important to underline that immediately after the first

pre-qualification phase, already in 2013, serious transparency problems had emerged

concerning two of the three qualified Lebanese companies.

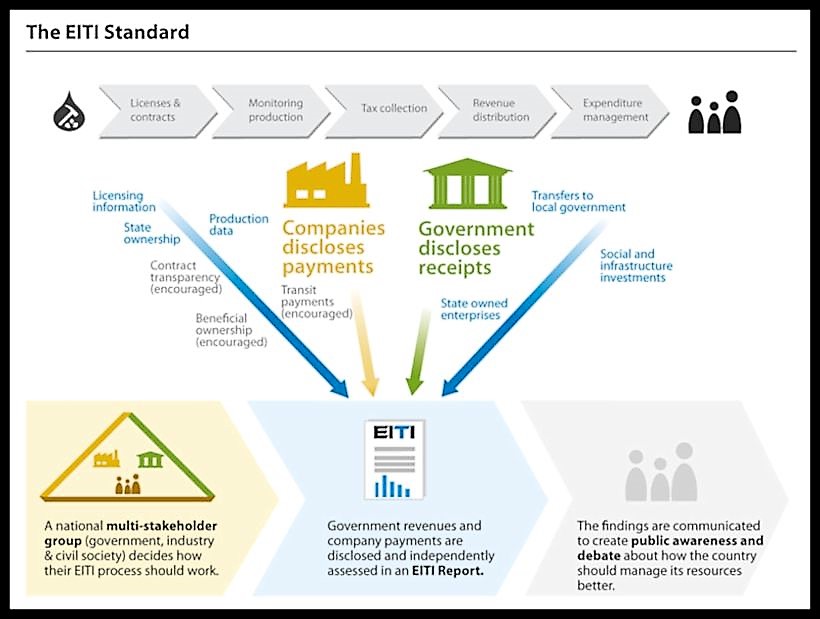

One positive, but limited,

note for the possible investors is that Lebanon has announced its intention to

join the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (E.I.T.I), which is a

voluntary initiative through which the government of Lebanon will commit to

publishing reports on how the government manages the oil, gas, and mining

resources. In practice, the participation in the E.I.T.I. will promote

transparency in the hydrocarbons sector. It would be quite important that

Parliament approved a draft law, which was prepared in the last two years, regarding

transparency in the O&G sector before November.

|

| The E.I.T.I. Standard — Source: E.I.T.I. |

There is a final question:

What companies could really be interested in investing in Lebanon? It’s

difficult to have an answer. U.S. Exxon Mobil, Chevron, and Anadarko, Brazil’s

Petrobras, Italy’s E.N.I., Denmark’s Maersk Spain’s Repsol, U.K. Shell,

Norway’s Statoil, France’s Total, Japan’s Inpex, Malaysia’s Petronas, and

O.N.G.C Videsh Limited all pre-qualified as operators—12 in 2013 and 1 in 2017.

Indeed, these companies are among the best I.O.C.s at world level. But it’s

quite probable that the interest they had in 2013 is not present any longer in

light of all the considerations developed above.

Recently, a few days ago, Foreign

Minister Gibran Bassil while meeting with his Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, encouraged China to invest in

Lebanon’s oil and gas sector. Normally, this type of exhortation would be

perfectly in line with the meeting. But when you are the foreign minister of a

country that is currently carrying out its first licensing round to which no

Chinese company will participate, such a behavior raises the doubt that the

pre-qualified companies haven’t until now shown excessive interest in the

licensing round and that Lebanon has to develop a plan B. Of course, this could

easily be just a simple conjecture because companies will submit their tenders

only on Sept. 15, 2017.

In particular, in view of

the considerations developed in this analysis, it could be difficult for an I.O.C.

to develop a good business case and decide to invest in one of the three blocks

comprising the disputed wedge of water. Moreover, Lebanon does not have the

naval capabilities to protect militarily its future O&G installations,

while Israel has powerful naval means.

But there is something

more. The sectarian divisions of Lebanese society, which are mirrored in the

country’s political institutions, until now have consistently and only slowed

the development of an O&G sector in Lebanon. What if instead the energy

sector with its consistent revenue stream became a new lever capable of

kindling another time Lebanon’s society internal conflicts?

For More Information Please See