October 8, 2013

BEIRUT, Lebanon

— The political relations between the Kurdistan Regional Government (the K.R.G.) and

Iraq proper with reference to the development of hydrocarbons remain tense and difficult. When

in September 2013, U.K. British Petroleum (BP) inked a letter of intent to

help Baghdad to develop the Kirkuk oil field, another element of friction was

added to the whole picture. What has been going on in Iraq — including Iraqi

Kurdistan — since the summer of 2011 is a positioning game between

international oil companies (I.O.C.s) in order to operate in specific swaths of

territory where there are consistent hydrocarbon resources. Historically, the

relations between Erbil and Baghdad have always been difficult, and oil and gas hunting

in the area is again pitting at loggerheads the K.R.G. and Iraq, which are offering

to the energy company two different types of contracts: production sharing contracts (P.S.C.s) for Erbil technical service contracts (T.S.C.s) for Baghdad.

The Current Situation in Iraq

and the K.R.G.

This positioning

game had its inception when the American oil supermajor, ExxonMobil decided to

start negotiating drilling contracts with the K.R.G. In this way the American company bypassed

Baghdad's authorization. In fact, Baghdad affirms that it alone has the right

to negotiate and sign energy deals for the whole Iraqi territory, the K.R.G.

included. Erbil insists that the Constitution of Iraq allows

it to agree to contracts and as a result to produce oil independently of the

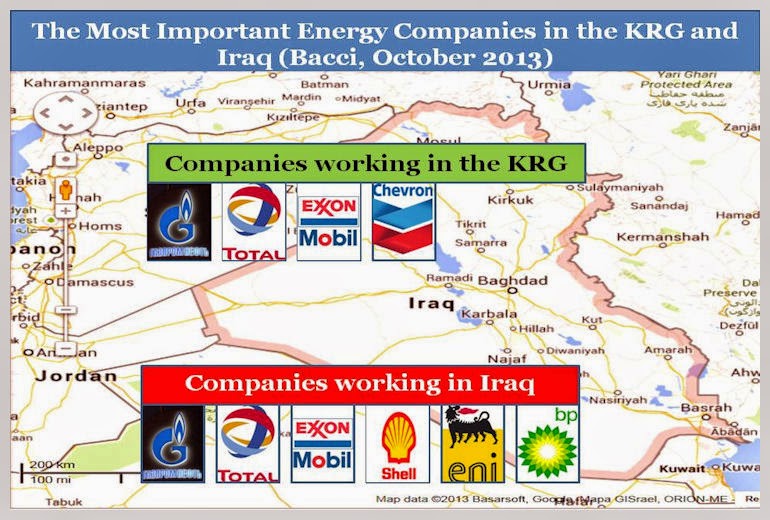

central government. In October 2011, ExxonMobil entered the K.R.G. energy sector acquiring six exploration blocks. Since then, given the better

contractual terms on offer in the K.R.G., other major I.O.C.s have been investing in

the semi-autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan. Presently, there are in Iraqi Kurdistan

around fifty international energy companies (among them four big names: U.S. ExxonMobil and Chevron,

France's Total and

Russia's Gazprom Neft), which have invested more or less $20 billion.

|

|

Source: The

Independent

|

One

point that should be clear is that I.O.C.s go where they deem to find profitable

opportunities for their business — only wildcatters may follow a partially

different logic. And I.O.C.s (and especially Big Oil) have the necessary

economic, managerial and technical requirements that give them the leverage for

investing also in very difficult environments — which could be difficult both

with reference to the required technical skills for recovering oil and gas and/or

for the political situation of the involved area.

Now, according

to the location of their investments in the K.R.G. and Iraq, I.O.C.s have three

different possibilities:

A)

Investing only in the K.R.G. (U.S. Chevron),

B)

Investing only in Iraq proper (U.K. British Petroleum and Royal Dutch Shell and

Italy's Eni),

C)

Investing in both the K.R.G. and Iraq (U.S. ExxonMobil, France's Total and

Russia's Gazprom Neft).

The

third possibility mentioned above places I.O.C.s in a sort of limbo because

Baghdad does not accept and consider completely illegal that I.O.C.s invest in the K.R.G. without its authorization. In

retaliation for their K.R.G. investments, Baghdad has menaced these companies of

outstripping them of the right to invest in Iraq proper if they do not stop

their K.R.G. operations. On the Erbil side there are no problems if I.O.C.s are

investing both in the K.R.G. and in Iraq proper, unless the operations deal with

that strip of land which is disputed between Erbil and Baghdad.

In

specific, it seems now that ExxonMobil will sell its stake in the WestQurna-1 oil field — one of the biggest world's conventional oil fields with 8.7

billion barrels — in southern Iraq favoring the company's investments in the K.R.G. "Exxon has decided to scale down, based on our request. We have asked Exxon to scale down on the West Qurna and they have decided to sell" said Iraq's deputy prime minister for energy affairs, Hussein al-Sharistani. He also added that, for the time being, ExxonMobil would

continue to be the operator of the field. The possible purchasers of

ExxonMobil's stake could be PetroChina and Indonesia's Pertamina.

BP's Letter of Intent for

Kirkuk Oil Field

One of

the companies that decided to stay on Baghdad's side is BP, which has recently,

in early September, signed a letter of intent with Iraq's central government to revive Kirkuk oil field. Already in

January 2013, the two sides had signed a preliminary deal for developing the same field. This letter of intent is important because it permits BP to operate

in the area disputed between Erbil and Baghdad. According to local sources,

this letter of intent refers to an 18-month deal for offering consulting services.

At the same time, it could be considered an interlocutory step, like the basis

for negotiating a long-term development contract. In this regard, it's already

evident that Iraq would like to move in the 18-month timeframe to signing a T.S.C., while BP would like to obtain better terms than the those of the T.S.C. it is has already signed in southern

Iraq.

The

major center of the disputed area is the ethnically mixed city of Kirkuk, which

is claimed by Kurds, Turkmen and Arabs — and to a certain extent all buttress

their claims according to different historical accounts. In an attempt to "Arabize"

the area of Kirkuk in the 1970s, Saddam Hussein's regime forced over 250,000

Kurdish residents to relinquish their homes to Arab people. Well before Saddam

Hussein played these in-Stalin-style forced deportations, according to the 1957

census Kirkuk was 40 percent Iraqi-Turkmen, 35 percent Kurdish and less than 25 percent Arab. The

huge importance of Kirkuk is linked to the fact that it sits on the giant

Kirkuk oil field, which as of 1998 owned around 10 billion barrels of oil.

Given

its importance, neither Baghdad nor Erbil wants to renounce to Kirkuk's area.

To give a sense of this: BP's operations will develop just west of the

ExxonMobil's developed area. And of course every initiative which involves the

disputed area always sparks objections: if, on the one side, Baghdad has always

opposed whatever hydrocarbon operations is carried out in the K.R.G. without its

permission, on the other side, Erbil has always stood against any hydrocarbon

operation in the disputed area like, for instance, BP's new involvement. "No company will be permitted to work in any part of the disputed territories including Kirkuk without formal approval and involvement of the K.R.G." affirmed in September a

spokesperson for the K.R.G. Ministry of Natural Resources.

Then, on Wednesday,

October 2, 2013, Arif Tayfur (Kurdish), the deputy of the Iraqi Parliament

speaker, strongly criticized Iraq's Ministry of Oil for signing the letter of

intent with BP. In specific, he affirmed that the agreement was illegal because it violated Art. 140 of the Iraqi Constitution, which says:

...

Second: The responsibility placed upon

the executive branch of the Iraqi Transitional Government stipulated in Article

58 of the Transitional Administrative Law shall extend and continue to the

executive authority elected in accordance with this Constitution, provided that

it accomplishes completely (normalization and census and concludes with a

referendum in Kirkuk and other disputed territories to determine the will of their

citizens), by a date not to exceed the 31st of December 2007.

The goal of the Article 140 is clear: Normalizing the

situation in Kirkuk and the other disputed areas, bringing back Kurdish

inhabitants, repatriating to central and southern Iraq the Arabs brought in to

Kirkuk by the Saddam Hussein's regime and, most importantly, conducting a new

census and then a referendum permitting the inhabitants to decide whether they want

Kirkuk to be annexed to the K.R.G.

Moreover, Mr. Tayfur requested that the Iraqi minister of oil, Abdul Karim al-Luaibi and the deputy prime minister for energy affairs, Hussein al-Sharistani took "into account the sensitive circumstance in

the country and to refrain from concluding contracts and agreements with

foreign Petroleum companies and control resources of the people, especially in

the disputed areas as differences still exist around these areas".

Kirkuk Oil Field and BP's Role

Presently,

Baghdad needs a qualified partner to revive an oil field that in the last

years has experienced an important output decline. According to local sources,

this letter of intent refers to an 18-month deal to offer consulting

services. At the same time, it could be the basis for negotiating a long-term

development contract. The British company will be working with reference to the

Baba and Avana geological formations. Instead, Kirkuk's third formation, Khurmala

is controlled by the K.R.G. and is developed by the Iraqi Kurdish KAR Group.

This

field was discovered by the Turkish Petroleum Company in 1927 and then seven

years later, in 1934, the Iraq Petroleum Company (I.P.C.) started production. At

that time — it's seems impossible in today's Middle East — 12-inch pipelines

brought oil from Kirkuk to Haifa and Tripoli (Lebanon). Today's oil production is

moved through the Kirkuk-Ceyhan Pipeline.

It's manifest

that it's really premature to speak about possible future contractual terms

when it's still unknown how complex the field is and what kind of intervention

it necessitates. It seems that at the beginning of this collaboration for the

Kirkuk oil field BP will pour in up to $100 million with two main and specific goals:

A) Stopping

the decline of the field. At this time the Kirkuk field produces more or

less 280,000 barrels per day (bbl/d) when in 2001 the production was around

900,000 bbl/d. The production has slumped by 70 percent and now Baghdad would like to

increase it to 600,000 bbl/d in five years.

B) Obtaining

a clear assessment of the field's potential. At present, some engineers

believe that bad reservoir management — like injecting water and dumping

unwanted crude and chemicals into the field — since Saddam Hussein's years,

could have seriously if not permanently damaged the field. In specific, due to

fuel oil re-injection, a big problem is oil viscosity, which complicates

extraction and of course increases the costs.

Why Did BP Decide to Invest

Only in Kirkuk? One Simple Reason: Rumaila Oil Field

BP

decided to increase its presence in Iraq because it has under contract the

development of the super-giant Rumaila oil field ($30 billion oilfield project),

which is located in southern Iraq, approximately 20 miles from the border with

Kuwait. This field is considered the third largest oil field in the world.

It's estimated to hold 17 billion barrels, i.e., 12 percent of Iraq's oil reserves, which are estimated at 143.1 billion barrels and it produces 1,400,000 bbl/d (data

of June 2013). Iraq owns the field, which is subcontracted to BP and China National Petroleum Corporation (C.N.P.C.). BP is an operator of the project with a 38 percent

stake, while C.N.P.C. holds a 37 percent stake and Iraq's State Organization for Marketing of Oil holds a 25 percent stake. The latter company is the Iraq's government

representative.

BP and

C.N.P.C. operate in Rumaila under a 20-year T.S.C., the Iraq Producing Field Technical Service Contract (P.F.T.S.C.) and, according to the initial terms, after having

reached an initial output target they recover a remunerated fee of $2 per

barrel (one important consideration is

that BP's initial offer was $3.99 per barrel). Interestingly, ExxonMobil also bid for this contract, but its

price of $4.80 per barrel was evidently much higher. At the end of 2009, BP

sources affirmed that BP had a rate of return (ROR) on the Rumaila investment

of 15 to 20 percent. A subsequent study by Deutsche Bank, a German bank, put the return even higher, at 22 percent. If BP has this ROR with a fee of $2 per barrel it is indeed doing

a good business.

On the technical

side, Rumaila is really a good asset for BP. When the company entered the field

after the 2009 contract, the oil field was in a shocking state of affairs — like all Iraq's petroleum industry following its nationalization (completed in

1972), the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88), the First Gulf War (1991) and the Second

Gulf War (2003) — but notwithstanding this, the field was producing approximately 1 million bbl/d. Part of this result is linked to the field's simple geology. In fact, the presence of a natural water aquifer is capable of maintaining the reservoir

pressure constant. Thanks to this oil may flow at an high rate.

Considering

this situation, it goes by itself that, at least for now, for fear of a possible retaliation by Baghdad, BP will not

look for new upstream opportunities in Kurdistan, although it's worth mentioning that according to industry sources,

Air BP is participating to a tender to supply fueling services at an airport in

Erbil. On the other side, for Baghdad, Rumaila is the most important asset

because it is the most important field of southern Iraq, the part of country that produces more than 67 percent of Iraq's total oil output.

BP

Accepted a $2 Per Barrel Fee, but Is This the Real Final Fee?

A technical

service contract (T.S.C.) is an agreement negotiated between a government entity

and an operating or service company. The goal is to perform exploration,

development and/or production services for fees and recovery costs, but with the

important caveat that the oil company does not own the right of booking

reserves. With Iraqi T.S.C.s, I.O.C.s

get only a small contribution per barrel while Iraq has full control and

ownership of the resources and companies have no right to lift, market or book

reserves, plus they bear all the capital expenditures and financial risks.

Obtaining $2 per barrel is remarkably a low price

for BP. Especially, if we consider that the fee is additionally reduced by a 25 percent fully carried state participation and by a 35 percent income tax. Moreover, in Iraq

according to the implemented T.S.C.s, the barrel per fee may be reduced by up to

70 percent as the R factor increases from 0.0 to 2.0 (the R factor is a sliding scale

that employs a ratio of two numbers to determine a rate. In the oil and gas business the most common R factor is obtained dividing cumulative revenues by

cumulative costs).

But there is a logic behind this contract and this

logic supports

Baghdad's decisions. Companies prefer P.S.C.s, but T.S.C.s could be acceptable

contracts when I.O.C.s have to work in an environment where there are proved

reserves and/or where the real activity is just related to a previously

exploited field (for instance, a redevelopment activity). Rumaila is a

well discovered area with huge oil reserves and this means that the risk for BP

is very low. All this said, with a $2 fee per barrel many analysts questioned

the profitability of the investment for BP ,especially with a boasted ROR around

20 percent.

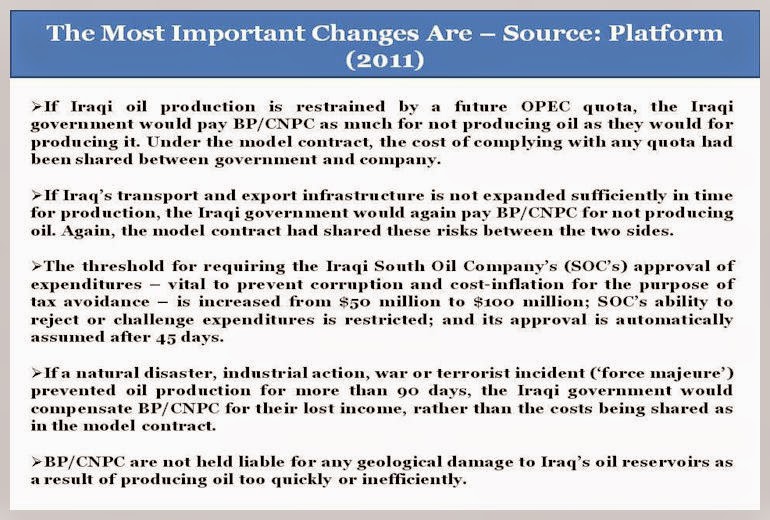

Three

months after the auction the Rumaila contract was privately renegotiated between

the Iraqi government and the winning consortium BP/C.N.P.C. The slide

below shows the five most important contractual modifications.

The effect of these changes is to transfer the most significant risks from BP/C.N.P.C. to the Iraqi government, making the contracts considerably more attractive to the companies. In all of these changes, it is

the Iraqi side that loses out. As a result of the enhanced compensation

provisions, the Iraqi government could find itself paying BP/C.N.P.C. (and likely

other companies) even when it is not earning oil revenues to offset those

payments. Meanwhile, the changes undermine the Iraqi ability to ensure that it

achieves value for money, and that oil is developed in the national interest.

It's

not the purpose of this analysis to decide whether the implemented renegotiation is

good or negative for the Iraqi government. Of course, it should be better

if contract were implemented exactly as they were awarded and not with

substantial modifications after just three months. Instead, what happened was a rebalancing of the contract where

in the end what the consortium was getting was not anymore $2 per barrel, but

much more, although this plus was given with different means. As Eni's C.F.O., Alessandro

Bernini pointed out in 2009, with reference to another renegotiated contract related

to the Zubair oil field, "we accepted $2 because, basically, the fiscal

terms are different now.” Moreover he added that the renegotiated terms with a

remuneration fee of $2 were equivalent to the pre-bid terms at a fee of $4.50.

A similar renegotiation happened as well for two other southern oil fields:

West Qurna-1 (ExxonMobil/Shell) and the above mentioned Zubair (Eni-led

consortium). In West Qurna-1 the

renegotiated fee was $1.90 from an initial bid of $4 and for Zubair $2 from

$4.80. The terms of the reductions implemented in West Qurna-1 and Zubair are

very similar to Rumaila's.

In Rumaila a Contract Renegotiation

Was Implemented but Is It Really Positive for Iraq?

With no

doubt Rumaila's contract renegotiation has given to BP an improved

contract guaranteeing the company to be paid also if the government did not receive

oil revenues to offset its payments. As for the renegotiated contract the

following five events:

A) a

potential OPEC quota imposed onto Iraq,

B) a

potential infrastructure risk,

C) less

Iraqi oversight for project expenditures, starting only over $100 million,

D) potential

security, political and natural risks and

E)

absence of liability for reservoir damage

do not

change anymore the economic profitability for BP, but they exclude now its liability. It is worth asking whether for Iraq it was not preferable

signing a simple T.S.C. with an increased fee per barrel on behalf of BP in order

to have an evenly split — between BP and the Iraqi government — liability in

the occurrence of one or more of the five points mentioned above. The five

mentioned events may well happen during a twenty-year contract, and currently a

potential risk infrastructure is already having a relevant impact as well as

some security risks.

Iraq's Poor Infrastructure and

Contract Renegotiations in Light of an Iraqi Oil Production of 9 million bbl/d (if Not a More Advantageous 6 to 7 Million bbl/d)

It's

quite notorious how southern Iraq does lack oil storage capacity so that delays

or weather-related interruptions to loading tankers force a company to curtail

production. And if reducing production is fast, lately reincreasing it is a long operation. This is just one single example of the infrastructural

gaps present in today's Iraq.

Since

December 2012 BP has been trying to renegotiate the terms of its Rumaila contract

with Baghdad. BP is facing difficulties in ramping up oil

production to the plateau level of 2.85 million bbl/d by 2016 as requested

according to the 2009 contract, although if the difficulties were related to

one or more of the five mentioned points, BP should always be paid. The company

would like to cut the initial plateau of 1 million bbl/d.

It's

quite possible that in the near future there will be an agreed-upon plateau

reduction between BP and Baghdad because the latter is lowering the plateau levels

in all its production fields in southern Iraq (it has already implemented a renegotiation of the plateau with Italy's Eni for Zubair and with Russia's Lukoil for West Qurna-2) in line with the new overall country target of 9 million bbl/d in 2017, before the target was the unreachable level of 12 million bbl/d. This level was

probably unattainable for at least three main reasons (of course assuming that

there would not be any security risks more than the average security risks in the area):

A) the

big infrastructural gap existing in Iraq,

B) a

possible collapse of the oil price as a consequence of pouring into the market 12 million bbl/d,

C) the

reintroduction of an OPEC quota for Iraq.

Iraq

does not have an OPEC quota following the sanctions from 1990 to 2003 and the

instability witnessed by the country following 2003. All this said,

traditionally Iraq's quota was matching Iran's and was something less than 4 million bbl/d before the invasion of Kuwait in 1990. A higher quota

could be expected to compensate the country's hardships but thinking of a

quota higher than 6 million bbl/d is very difficult. And six million is exactly half the

production that in 2009 Iraq was planning to produce by 2017.

Conclusion

The

basic idea of this article was to show that, in a competitive process, oil companies

make bids based on their evaluation of the risks and the rewards of the

project on offer. No big company implements any deal without a careful

assessment of the pros and the cons involved in the operation. The Rumaila contract

well suits this idea. Similarly, as a consequence

to economic considerations, linked mainly to more profitable contractual terms

it was quite normal that some I.O.C.s deemed interesting to invest in the K.R.G.

where productions sharing contracts (P.S.C.s) were, and are, on offer. Booking

reserves and profiting from a high oil price are two relevant incentives for

P.S.C.s. But again, generalizing that companies want only P.S.C.s is too simple a way

of thinking. Also T.S.C.s, if structured in a balanced manner, could be profitable

for I.O.C.s.

The

Rumaila contract also shows us that when in the energy field two heavyweights like

BP and the government of Iraq do business together there is ample room for

continued negotiations. It's difficult to arrive at rupture points between such

two parties ,and there is a lot of negotiating activity conducted

behind closed doors, which hardly ever reaches the headlines. In Rumaila, it's possible

that there will be a reduction of the plateau of production probably in the

direct interest of both parties. And if BP could gain more profits not reducing

the plateau and applying the five liability exemptions, it's presumable that there

could be for the British company other profit-generating opportunities with Iraq in the long term in Rumaila or in other locations (for instance, in

Kirkuk?). In other words, you may lose something on one side, but you may gain something else on

another.

For next December 19, the Iraqi oil industry is planning to auction the giant Nassiriya oil field (4 billion barrels of oil) located as well in southern Iraq (part of the project includes the construction of a 300,000 bbl/d refinery). According to released information, the terms

of this contract will be different than those of the previous T.S.C.s. First of

all, operators will not have a state partner and no signature bonus will be

paid. When production begins, the investors will be offered a share in the project

revenues and the ministry will pay recovery costs from the date of the commencement

of work. Investors will have to pay 35 percent taxes on profits like in the previous

rounds.

With

no doubt this revised T.S.C. could be a positive step forward after the failure of

the Iraqi fourth bidding round and the complains that Baghdad has been receiving

in these last years with reference to the the slim margins oil companies have been obtaining

(See for more details: BACCI, A., Chevron and Total Continue Investing in the K.R.G. A Brief Analysis of Baghdad's T.S.C.s vs. Erbil's P.S.C.s).

A contract to be

successful needs to be balanced among the involved parties. When it's possible to

strike such a balance then normally a contract is signed. And contracts need to

be completely understood in order to have a clear assessment of their

profitability. Simple formulas, like T.S.C.s or P.S.C.s, many times do not provide the

whole picture. The devil is in the detail(s) in a negative and/or positive

meaning. And with oil contracts sometimes it's more appropriate to use the

other older idiom: "God is in the detail".