The

analysis “The Islamic State Oil Industry Is a Pipe Dream” has been initially

published by Oilpro, a professional network for the oil and gas professionals.

July 3,

2016

CALGARY, Canada — While I am writing this

analysis, we have still to metabolize the great sadness related to the two

terrorist attacks that have occurred in the last few days. The first one at the

Ataturk International Airport in Istanbul, Turkey, where more than 40 people

were killed. The second one at an upscale restaurant in the diplomatic quarter

of Dhaka, Bangladesh, where 20 people were killed. It’s indeed another very gloomy

page of the endless terrorist attacks against civilians. These horrible attacks

against innocent people are very difficult to intercept and to stop. Reality and

rationality tell us that we have to live with the possible remote (per single

person) occurrence of such events. Logic and probability would dictate to us

that we should rationally worry more the possibility of dying of several

diseases than about the possibility of being killed by a terrorist attack — but

it’s not easy to be calm and rational when terrorist events occur. For sure, introducing

a police state will not be a solution; introducing a lot of restrictions would enormously

limit our way of living. And, living under a police state would be a victory

for the terrorists of every kind.

The basis for this analysis is primarily based on

a conversation I had some months ago, precisely a few days before the attacks

in Paris, with a U.K. film director interested in the current developments in

Syria and Iraq, i.e., the emergence of the Islamic State, a.k.a. ISIS or ISIL.

The director wanted to have my opinion about the economic strength of the

Islamic State; he was very well informed about the current war developments in

Syria and Iraq. But, like many other researchers and journalists, he had a sort

of “worried excitement” in relation to the Islamic State. I told him that I was

expecting other terrorist attacks across the globe — a few days later occurred

the Parisian attacks — but that with reference to the economic power of the

Islamic State I was quite skeptical at least as for the possibility of

establishing a real and functioning state in the areas under the Islamic State’s

control. After some months, I am still deeply convinced that at the economic

level the Islamic State does not have good prospects. Let’s see why.

In Iraq, the effective territorial prominence of

the Islamic State started in early 2014, when during its western Iraq

offensive, a.k.a. as the Anbar offensive, the Islamic State was able to push Iraq’s

government forces out of key Iraqi cities. After that offensive, on June 10,

2014, the group captured Mosul, a city home to 2.5 million people and a

relevant center for crude oil production located in northern Iraq. In Syria,

during the Syrian Civil War, in 2013, the city of Al Raqqah was captured by the

Islamic State, which in 2014 made this city its headquarters in Syria. Raqqah

is the de facto capital of the territory under Islamic State’s control in Iraq

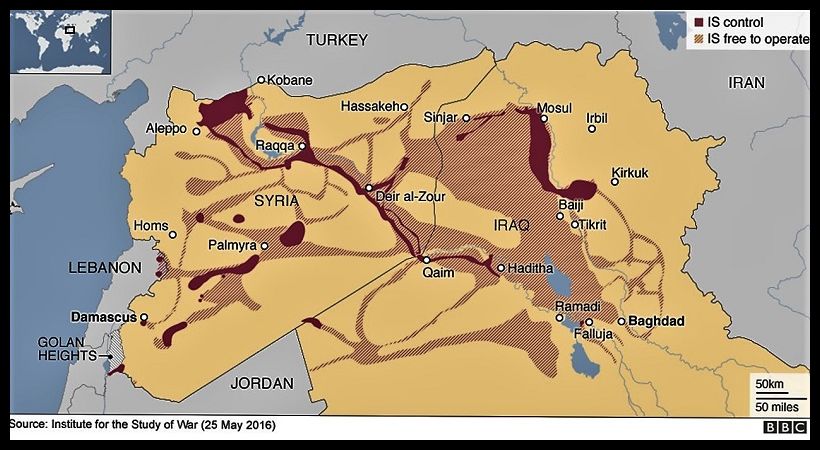

and Syria. In brief, the Islamic State currently controls a vast area straddling

between eastern Syria and western Iraq. In specific, the Islamic State controls

vast areas of the following governorates:

- in Syria: Aleppo, Al Raqqah, Deir ez-Zour, Homs, and Rif Dimashq

- in Iraq: Al Anbar, Saladin, Kirkuk and Nineveh

Theoretically, approximately 10 million people

should live in the Islamic State-controlled territory in Iraq and Syria —

exactly twice as much the population of the Kurdistan Regional Government (the

K.R.G.), which according to K.R.G. cabinet sources stands at 10.2 million

people. It’s important to understand that both in Iraq and Syria there are

large swaths of territory where, although it does not have direct control, the

Islamic State is completely free to operate. According to U.N. reports, 4.8

million Syrians have been forced to flee abroad, primarily to Turkey (2.7

million) and Lebanon (registered 1 million but the refugees are probably 1.5

million exerting a huge impact on the already not brilliant Lebanese economy).

In Iraq, still according to U.N. data, there should be more than 3 million

people who are now internally displaced.

Since its apogee in the summer of 2014, the

Islamic State has lost around 40 percent of its territory in Iraq and 10 to 20

percent of its territory in Syria. According to the latest U.S. intelligence

estimates, the present number of Islamic State recruits is put at 25,000;

indeed, there has been a consistent decline in the number of recruits over the

previous months, although in light of the contingent situation in both Iraq and

Syria, these statistics are not a 100 percent reliable. A total of 25,000

Islamic State fighters have been killed by the U.S.-led airstrikes in the

region. But, unless Western countries decide to scale up their intervention,

with all the unknown possible outcomes that may derive from a Western presence

on the ground, reconquering the lost cities in Iraq is a very lengthy process.

For instance, Ramadi, in Iraq, was reconquered by Iraq’s government forces only

after an offensive that lasted several months. In Syria, where getting some

sense of the civil war, an ongoing multi-sided armed conflict with

international interventions, is even more complicated, trying to stabilize the

country is right now almost an impossible task.

Is the

Islamic State Rich? It Depends From What It Means to Be Rich

It goes by itself that the Islamic State needs

money in order to:

- fight in Iraq and Syria

- manage the territory it controls in Iraq and Syria

- conduct terrorist attacks in other countries

The difference between the

Islamic State and some other terrorist groups is that it controls a vast territory.

And from this territory, it derives several revenue channels. It is on a grand

scale a replica of what happens in some cities across the globe (for instance, Caracas,

San Pedro Sula, San Salvador) where the police do not dare to enter some

neighborhoods because it would be outgunned — in other words in these cities as

well as in the Islamic State-controlled territory the official rule of law is

not applied. Having a precise estimate of the Islamic State’s revenues is not

easy because these local revenue channels may vary consistently from month to

month. At the time of this writing, three are the most important sources of

revenue: taxes and property confiscation (together around 50 percent), and the

sale of crude oil (43 percent). The latter was initially the most important of

the Islamic State’s revenues. Other sources of financing are the sale of

antiquities, drug smuggling, banks reserves, ransom for hostages, and donations.

When the Islamic State conquered Mosul, it found something like half billion dollars

in the Mosul branch of Iraq’s Central Bank, but of course this was a one-time

revenue source.

According to the Rand

Corporation, a U.S. policy think tank, in late 2008 and early 2009, the Islamic

State earned around $1 million per day, while in 2014 it was able to collect an

amount ranging from $1 million to $3 million per day. So, assuming that the

Islamic State is able to collect $3 million per day, this is equivalent to $90

million per month (best case scenario for the terrorist group). But, these

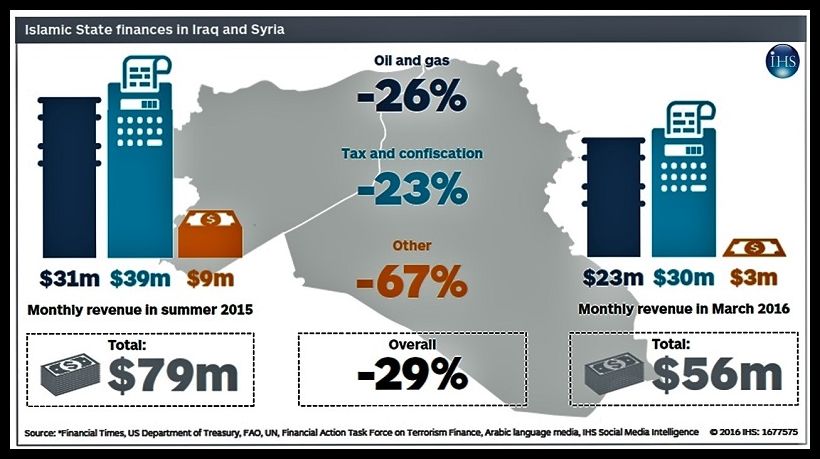

estimates are too optimistic. In fact, I.H.S., a consultancy, reported that as

of March 2016, the Islamic State’s revenue per month experienced a 30 percent

decrease to $56 million from a value of $80 million per month in mid-2015.

These numbers tell us one main

thing: $56 million per month, but it would be the same if the Islamic State

still collected $90 million, is a high amount of money in order to carry out

terrorist operations around the world, but it is absolutely insufficient in

order to run a territory that the Islamic State would like to transform into a

fully fledged country. Managing a territory is a much more complex and

expensive task. For instance, the K.R.G.’s population is practically half the

Islamic State’s population. And, the Kurdish government estimates that to manage

the K.R.G., an autonomous province within Iraq, it needs $850 million to $1

billion per month, which should be equivalent to the 17 percent of the federal

budget. The Iraqi Constitution assigns 17 percent of the federal budget to the

K.R.G. Today, between Erbil and Baghdad there is again a strong confrontation

as for the distribution of the revenue obtained from selling the K.R.G.’s and

Iraq proper’s oil via the Kurdish pipeline — in March 2016, Iraq’s central

government decided to stop its oil exports via the Kurdish pipeline system

(more details below) because of disagreements with the K.R.G. on oil revenues. In

both the K.R.G. and Iraq proper, under the current strained circumstances (a

war against the Islamic State, low oil prices, and 3 million of internally

displaced people), it’s quite improbable that the budget may permit Baghdad to

transfer $1 billion a month to Erbil, but at least it gives us an idea of the

financial burden required to run a country of 5.2 million people in that area

of the Middle East — although it’s true that geography of the K.R.G and that of

the Islamic State territory is quite different (mountain vs. desert plain). The

fact that, in 2015, the Islamic State approved a budget of $2 billion confirms

that its revenues are not comparable to the revenues of a standard country.

So the real question is

whether the Islamic State has abundant economic resources to at least barely

run a territory spanning between Iraq and Syria. And the answer is no. The

economic means that it has right now at its disposal are absolutely not

sufficient. Resorting to terrorism — although a constant in Iraq’s life after

the fall of Saddam Hussein — is a manifestation of a weak position versus

adversaries more powerful; adversaries who cannot be won in an open political

confrontation or in a fight according to international humanitarian law

(I.H.L.), a.k.a., jus in bello.

In addition to these

economic considerations, after the immediate fall of Saddam Hussein and during

the years of Nouri Al Maliki’s government (2006-14), the Islamic State

partially found fertile ground in Iraq thanks to the disenfranchisement of the

Iraqi Sunni population, around 35 percent of Iraq’s population — an important

caveat: some Sunni groups helped the invasion of Iraq by the Western powers,

but later they were never rewarded for their help by the new Iraqi

administration. Instead, during Saddam Hussein’s period, Sunnis were the

majority of the Ba’athist government and enjoyed a special treatment. In brief,

today the economic conditions of most Sunnis in Iraq are at the root of their

support for the Islamic State. In fact, apart from some areas in Baghdad and

the city of Mosul, most of Iraq’s Sunnis are farmers, who have been hit hard by

the poor harvests and food shortages of the last years — in Iraq, after 2003,

agricultural productivity declined by 90 percent. In other words, poverty and

political marginalization pushed many Sunnis toward the Islamic State. In the Middle

East, the identitarian affiliation has always been a very powerful political tool.

Especially when life is harsh and the future is bleak, the normal behavior is

to more tightly embrace one’s identitarian affiliation, no matter whether the

basic ideology is not supported a 100 percent. This is exactly what happened

between the disenfranchised Sunnis and the Islamic State ideology.

The

Islamic State and the Sale of Crude Oil

As mentioned above, the

Islamic State obtains half of its revenues from taxation and confiscation in

the territory it controls. It’s evident that the wider territory it controls

and the more people live in that territory, the higher are the rents for the

Islamic State. Over the last year the Islamic State has lost ground in both

Iraq and Syria, so it has now a reduced taxable base. Despite the importance of

taxation and confiscation, I would like to develop some considerations on the

relation between the Islamic State and the sale of crude oil. The reason behind

this choice is that last fall during my conversation with the film director a

lot of attention was given to the flow of revenues the Islamic State obtains

from crude oil sales — in addition to this, I am a petroleum consultant (legal

and fiscal issues), while I do not know much about selling antiquities,

smuggling drugs and so on.

A petro-state is a country

that depends on petroleum for:

- 50 percent or more of export revenues

- 25 percent or more of G.D.P.

- 25 percent or more of government revenues

Under this definition, the

Islamic State may well be defined as a petro-state. Putting aside considerations

about whether it’s good for a country to be a petro-state (also the well

managed Norway is a petro-state), the real issue is that the Islamic State is a

“very poor” petro-state. In other words, its petroleum revenue is insufficient

to administer the territory it controls. Revenues are insufficient today, when

the Islamic State approximately produces 21,000 bbl/d, and were insufficient in

2014 and 2015 when its production was higher — in August 2014, before the

beginning of the U.S. airstrikes production hovered around 70,000 bbl/d.

For the petroleum

industry, the advance of the Islamic State has created a lot of economic

damage, especially in Iraq — Syria is today a minor oil producer at the world

level. Luckily the Islamic State has completely been unable to reach two out

three of Iraq’s main oil-producing areas, i.e., southern Iraq and the K.R.G.

The third area, Kirkuk Province, sees the presence of both Kurdish forces and

Islamic State forces, but the most important oil fields, technically still under

federal jurisdiction, are under Kurdish control. As a result of the presence of

the Islamic State in central and western Iraq, the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline has

in operation only the section related to the Turkish part from Fishkhabur (Iraq-Turkey

border) to the port city of Ceyhan in Turkey. The Iraqi section of the

Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline (from Kirkuk to Fishkhabur) has been out of service

since March 2014 as a consequence of repeated militant attacks. In fact, this

pipeline runs through Islamic State-controlled territory. So, since May

2014, the K.R.G. has been exporting its crude oil to Turkey via its new Kurdish

pipeline system, which is connected to the Turkish section of the Kirkuk-Ceyhan

pipeline. This new Kurdish pipeline system was then expanded from Khurmala to

the Avana dome in the Kirkuk area with the express goal of facilitating export

from the Makhmour, Avana and Kirkuk area fields. In fact, these fields had been

unable to export since March 2014 because the standard Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline

had been damaged by the Islamic State.

In the territory the

Islamic State has conquered in both Iraq and Syria, it has the control of

practically all the oil fields and the related infrastructure, but it may use

them only in a very limited way. In fact, since August 2014, the U.S.-led airstrikes

have consistently reduced oil extraction inflicting a lot of damages to the oil

industry. In specific, Operation Tidal Wave II, a U.S.-led military operation

that started at the end of October 2015, targeted oil transport, refining and

distribution facilities and infrastructure under the Islamic State control.

According to the U.S. forces, in just two months, Operation Tidal Way II destroyed

90 percent of the Islamic State’s oil production. In addition to this, the

Islamic State has also to face the difficulty of substituting aging as well as

broken infrastructure. Similarly, it is not easy to find engineers and

technicians able to operate the oil fields — the call for recruiting these

types of professionals started immediately during the advance of the

spring/summer of 2014. The way the group managed the Baiji refinery, which is

130 miles north of Baghdad, well testifies to these difficulties. The refinery

had a capacity of 170,000 bbl/d and supplied petroleum products for northern

Iraq. After the Islamic State captured the refinery in June 2014, the refinery

started to produce only a fraction of its rated capacity because of lack of

personnel and oil supply — Iraqi forces retook the refinery five months later.

As mentioned above, the

Islamic State is experiencing a reduction in its overall oil production. It’s

currently producing around 21,000 bbl/d. It’s quite evident that in order to

move this oil the Islamic State has to use exclusively trucks. But shipping oil

by truck is an expensive means, especially when oil prices are low. Tank trucks

are described by their size or volume capacity. Large trucks typically have a

capacity ranging from 20,800 liters to 43,900 liters. The present capacity of

the Islamic State could be moved with as many as 76 43,900-liter tank trucks.

Furthermore, in light of

its illegality, this oil has necessarily to sell at a discount. As a means of

comparison, last year when prices averaged $52 a barrel, the K.R.G. was able to

cash in $36 a barrel, while in February 2016, when Brent was $32 a barrel, the

K.R.G. cashed in $20 a barrel. Of course, although in Baghdad someone might

dissent on this point, for a potential buyer one thing is to buy from the

K.R.G. and one completely different thing is to buy from a terrorist

organization. In other words, the oil of the Islamic State should be consistently

sold at an important discount in comparison to Brent. Reliable data are not

available, but it has been reported that the Islamic State’s oil from Syria

sold at as little as $18 per barrel when Brent sold at $107 per barrel.

In brief, part of the Islamic

State’s oil is sold on the black market along the very much permeable borders between

the Islamic State and the neighboring countries. The Islamic State primarily

refines oil in small rudimentary mobile refineries having a capacity of 300 to

500 barrels per day. Also this refined oil is shipped to Turkey via truck,

although some of this oil has been sold to the Syrian regime — pecunia non olet. Refining has always

been a problem for the Islamic State because by October 2014, 50 percent of its

refining capacity had been destroyed by the U.S.-led airstrikes. Moreover, in

both Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State gets profits as well from selling oil to

its captive markets at a price higher than the one obtained when exporting oil

abroad. And in Iraq and Syria, people desperately need oil for their daily

activities; in many areas diesel generators are essential because otherwise

there would be no electricity.

When assessing the Islamic State, the most

important first step is to decide whether to consider it a state or a terrorist

organization. If the Islamic State is state, it is indeed a poor and

dysfunctional state. It may control a territory straddling between eastern

Syria and western Iraq, but it will always be difficult for this hybrid state

to consolidate its position. A state in order to thrive needs a functioning

economy, which is something that the Islamic State completely lacks. Instead,

its economy is a looting economy, i.e., an economy based on the indiscriminate

taking of goods by force as part of its military victories. Continuing with

looting activities (the present futile taxations based on the Islamic State-imposed

new norms are nothing more than disguised looting) after several months is a

clear sign that the Islamic State will never succeed in establishing a normal

state. Instead, if the Islamic State is a terrorist organization, it is indeed

a very rich organization in relation to its terrorist activities. Indeed, it’s

an organization that has the economic capabilities of committing atrocities in

several countries. Especially now, in light of the recent difficulties in the

Iraqi theater, it is highly probable that Islamic State terrorists will continue

to export to other countries the present Iraqi-Syrian mess. The oil business is

a very complex and complicated business, so, since the beginning of its

territorial expansion, it was out of question that the Islamic State, a

terrorist organization, could have continued developing Iraq’s and Syria’s

petroleum sector — this idea was already even more clear after the beginning of

the U.S.-led airstrikes. In other words, from an economic point of view, the

Islamic State may implement only one technique: pillaging.