The analysis “A Crude Oil Glut, Low Oil Prices and the Problematic Fiscal Budgets of Many Oil-Producing Countries“ has been initially

published by Oilpro, a professional network for

the oil and gas professionals.

February 3, 2016

HOUSTON, Texas — W.T.I and Brent are telling us a

narrative of low prices. W.T.I is valued $29.70 a barrel and Brent $32.53. With

no doubt it a sea change from the values of June 2014 when oil prices stood at more

than $110 a barrel. Apart from a certain dose of structural short-term irrationality

of the commodity markets (sentiment), it is a fait accompli that crude oil producers are extracting more oil than

the oil really purchased on a daily basis. Today, there are approximately two million and

a half of crude oil barrels in excess; production hovers around 96.3 million

barrels per day (bbl/d), while demand is 94.5 million bbl/d. These barrels in

excess, which amount to 1.8 million bbl/d, are stored in tanks and tankers (the

U.S. is currently on an expansion spree with reference to its storage units for

crude oil); in practice who owns these barrels is waiting for better times in

order to sell them — some inventories have grown driven by the expectation of

higher prices in the coming months (the contango effect, i.e., high inventories

lead to a discount in the spot price relative to the forward price, generating

an upward slope in the forward curve). For the time being, places where to

store these unsold barrels are still available, but of course these exceeding

quantities are at least partially slowly filling them up at least in the U.S. According

to the Energy Information Administration (E.I.A.) the U.S. has a total capacity

for oil products (not only crude oil) of a little more than 1,500 million

barrels and a maximum crude oil capacity of 551 million barrels. Current crude

oil inventories are around 500 million barrels. Real numbers concerning storage

capacity are not easily available at the world level because outside of the

O.E.C.D. countries there are really scarce data.

It’s evident that there is a glut of crude oil. In

fact, one of the primary reasons for this 70 percent reduction in the crude oil

prices in just eighteen months is the increase in the number of barrels

produced in the U.S. over the last years. Shale oil has become a reality, and

America has been able to increase its production by 4.2 million bbl/d over the

last five years (these added barrels are equivalent to 4.3 percent of the

overall present crude oil production at the world level) — it’s indeed a very significant

increase. On top of this, slow growth in the global economy has compounded the

reduction in the price of oil. In this regard, some analysts have put the blame

on China’s economy, which has partially slowed down, but a detailed analysis

show that, notwithstanding a reduced economic pace, China is still buying its

average quantities of crude oil, at least until now. In general, low oil prices

should stimulate global economic growth because both oil-utilizing industries

and normal citizens save more money, but this time this phenomenon, i.e., the

benefits to oil-consuming nations, which typically outweigh the costs to

producing ones, are not occurring.

THE

SAUDI STRATEGY

Recognizing the changed market conditions, in

November 2014 during an OPEC meeting, Saudi Arabia forced the other member

states not to cut their oil production but to continue to produce at full

speed. The reason was quite simple: Because most of the OPEC members — and

among them the Persian Gulf producers — have very low productions costs, while

shale oil producers have higher production costs (although some recent

improvements have in general reduced the production costs of the U.S.

unconventional oil), Saudi Arabia wants to maintain OPEC’s market quota and to push

toward bankruptcy many American producers. In the 1980s, when OPEC decided to

cut production in order to sustain crude oil prices, initially it ended up

losing a relevant market quota in favor of the North Sea producers; only after

five years, in 1985, Saudi Arabia inverted its position flooding the market

with cheap oil — as a consequence oil prices went as low as $10 per barrel.

Within OPEC the present Saudi strategy is well supported by Kuwait and the

United Arab Emirates, but some other member countries are not convinced because

they desperately need money in order to run their daily government operations; outside

of OPEC also Russia would like to implement some production cuts, although for

Russia, in light of its ageing fields and limited production technology, it’s

easier said than done. Within OPEC, only Indonesia has a mixed economy; all the

other member states are strongly dependent on the revenues they get from

selling crude oil, so that when the price of oil is low, they consequently earn

fewer dollars.

Over the last years Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar

and the U.A.E. have been able to put aside relevant financial resources so that

they are able now to endure a period of low oil prices — although this

translates immediately in an increased financial deficit. For instance, Saudi

Arabia after the price reduction of the last months has still $630 billion in

financial reserves, but every month Riyadh now spends between $5 billion and $6

billion of these reserves — Saudi Arabia’s foreign reserves fell by $100

billion last year and a double-digit budget deficit is expected this year as

well. It’s clearly evident that Saudi Arabia’s financial position is not as

good as it was in June 2014, but Riyadh has plenty of room to maneuver, which

means that it could continue along this path of low oil prices for several

months. A similar consideration could be done for Kuwait, Qatar and the U.A.E.

In other words, all these countries, at least in the short term, are able to

maintain their social contracts (the generous allowances to which their

citizens are entitled).

A much more complex picture emerges from an

analysis of the economic conditions of countries such as Iraq (and the semi-autonomous

Kurdistan Regional Government, the K.R.G.) and Venezuela, within OPEC, and

Russia outside of OPEC. These countries desperately need to have higher oil

prices for fear of an economic collapse. Let’s consider Iraq proper and the

K.R.G., which, in addition to facing already difficult economic conditions, are

waging a war on the Islamic State. Iraq’s federal budget for 2016 forecasts a deficit of $20.1 billion (24.1 trillion dinars), but

there are two significant factors that could undercut the projected $68.1

billion in revenue. In fact, the budget envisages oil exports of 3.6 million bbl/d and an oil price of $45 per

barrel. In particular, current crude oil prices are quite far from the price

posted in the law. It’s also important to remember that Basra Light Crude sells

at a discount to W.T.I. (the benchmark for the U.S.), to Brent (the benchmark

for Europe) and to Dubai Crude (the benchmark for Asia). The K.R.G. has racked

up $18 billion in debt and experiences difficulties in paying governments

employees and security forces. At the same time, Iraq proper tries to avoid the

above mentioned possible budget shortfall. Last year it obtained a loan from

the World Bank, and it would like to obtain some other funds from the

International Monetary Fund (I.M.F.). Moreover, as a consequence of the decline

in the price of oil, Baghdad is seeking a renegotiation of its Technical

Service Agreements (T.S.C.s) with the international oil companies (I.O.C.s)

working in Iraq proper.

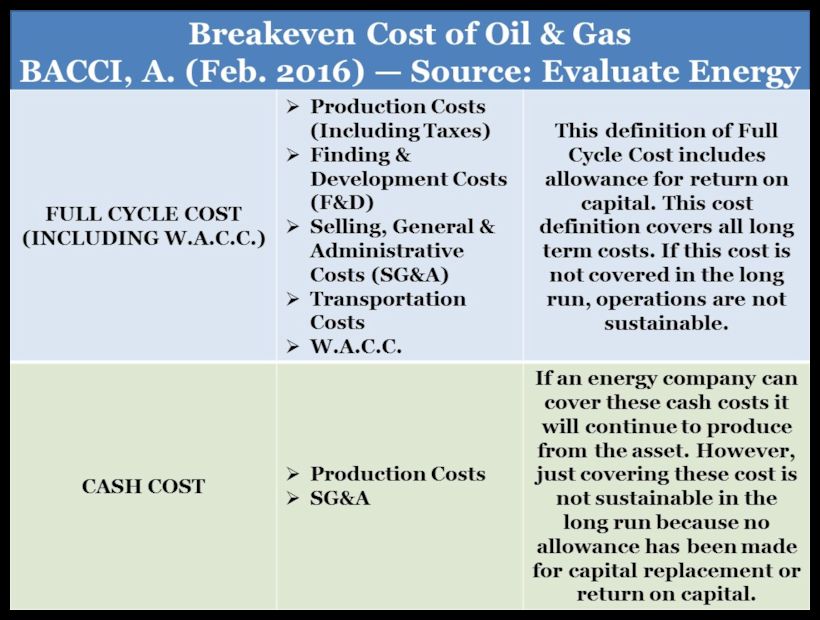

Because the world is awash with crude oil, oil

firms have put off investments in the order of $380 billion of new projects. And

if history is any indication, later these postponed investments will probably contribute

to an increase in the oil prices; in the oil business, with reference to

conventional oil, if you do not invest every year you normally have a 6 percent

natural decline in the production rate. And estimates tell us that the world

oil market will need another 7 million bbl/d of production by 2020. The U.S. is

slowly cutting production (from 9.6 million bbl/d to 9.2 million bbl/d); dozens

of small companies working with shale oil have gone bankrupt; oil producers

have dropped their rig count. But, as usual, the readjustment in the oil

industry takes time. In fact, if an energy company can cover PRODUCTION COSTS

and SG&A (selling, general and administrative expenses), it will

temporarily continue to produce from the asset because stopping operations with

all the involved sunk costs will cost more. Of course, this is only a temporary

procedure because a company needs to earn a profit on top of the capacity of

covering all the incurred expenses (including CAPEX and RETURN ON CAPITAL). In

the meanwhile, U.S. banks are putting aside reserve in order to absorb

additional losses linked to the impossibility of oil producers to repay their

loans, although it should be pointed out that, thanks to hedging mechanisms,

many energy companies are still receiving as much as $80 a barrel; the hedging

effect should conclude its trajectory over the first months of 2016.

WHERE

WILL THE NEW CYCLE BE ON A PRICE MAP?

In the long run oil prices are cyclical: The

upswing of the cycle is eventually followed by the downward slope and then

another cycle starts again. The real problem in the oil markets is not to

understand what the final future oil price will be (an impossible task), but

what type of prices will develop once the glut is over. The price of oil is the

combination of asymmetric and missing information; of the necessary investment

of conspicuous and often highly leveraged capital expenditures over a long

lead-time horizon; and of financial price discovery, i.e., the interactions

between buyers and sellers. Is this kind of combination ever able to result in

a permanent state of equilibrium? No. Balance occurs by accident and only for

short timeframes.

In other words, we have to take for granted that

oil is an inelastic commodity and that oil markets are cyclical and subject to

extreme volatility. Today, financialization rules; the traded physical oil is

probably 30 times smaller than the traded volumes of oil derivatives and

options. But, other question is trying to understand what the position of the

new cycle will be on the price chart, and what a possible, but temporary,

equilibrium price will be? In this regard, some preliminary considerations have

to be introduced. In fact, today, notwithstanding:

- a war in Libya (a producer),

- a war in Iraq proper and the K.R.G. (both producers),

- a crippled oil industry in Iran as a consequence of the international sanctions imposed on the country; the sanctions have been only recently lifted (a producer),

- a war in Syria (a relevant geopolitical actor in the Middle East) and

- an ageing oil industry in Russia (a producer),

there is an oil glut of almost 1.8 million bbl/d. And,

it’s sure that all of these countries are interested in re-entering the oil

markets or in expanding their oil production. Moreover, some “stable” countries

had already plans to expand their current oil production as well. For instance,

some years ago, Kuwait envisaged the necessity of bringing its oil production

to 4 million bbl/d by 2020 from the current production of 3 million bbl/d, and

despite the low oil prices, Kuwait is still committed to achieving this

target.

So, in light of these considerations, are we

entering an era of abundant oil? It’s difficult to say. What scares is that, if

they want to obtain the breakeven of their fiscal budgets, many of the

oil-producing countries need a level of oil prices completely misaligned with

what the prices of the new oil cycle could be — a cycle that could accommodate

more producers. When Saudi Aramco pays around $5 of OPEX to extract a barrel of

crude, but then Riyadh needs an oil price of $93 to balance its national fiscal

budget, there is something scary. And the same is true for all of the Middle

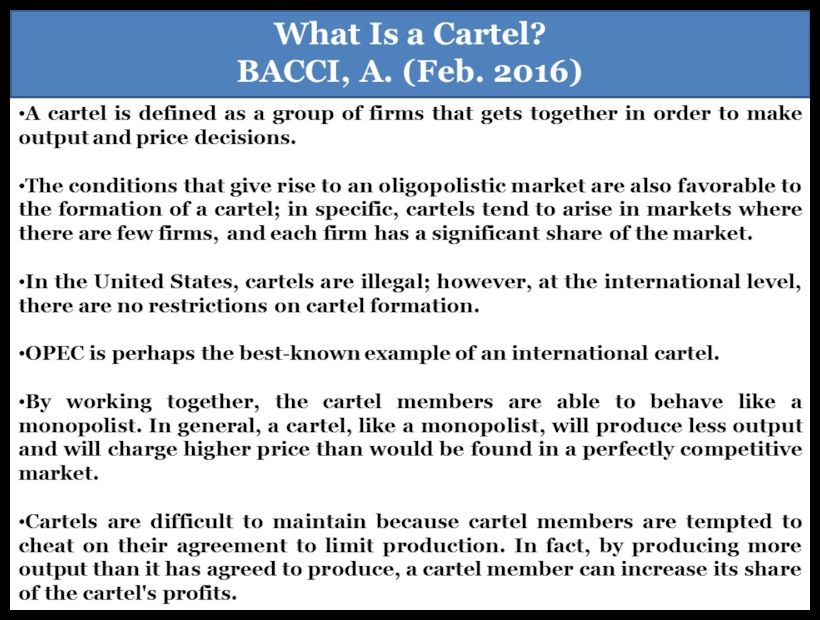

Eastern producers. The importance of OPEC, a cartel, lies exactly in

maintaining high prices while restricting competition. But, it is worth noting that

a cartel is able to control the shape of the forward curve, i.e., the cyclical

component of the price of oil but not the long-dated oil prices, i.e., the

structural factors. OPEC member countries produce about 40 percent of the

world’s crude oil and need high oil prices in order to compensate the almost

complete lack of diversification of their economies.

IS THE OPEC GAME STILL PLAYABLE IN THE FUTURE?

The answer will depend on several question marks.

One of the them is if the U.S. shale producers will be able to cut their

production costs. It’s difficult to fathom what the cost to the U.S. frackers is and will be. In fact, there are very different estimates. According to

WoodMackenzie, an energy consultancy, most shales are profitable to drill at

$50, but the same company has changed its estimates more than one time in the

last few months. Two years ago a shale well cost in the Bakken around $12

million, today it costs $6 million. These preliminary data (be it clear not

confirmed) seem to show that U.S. the shale oil will at least outcompete

deepwater oil, oil sands and Arctic oil. Second question mark: It is evident

that the “troubled” countries mentioned above if stabilized will increase their

production (only Syria has a negligible oil production), but how much will they

increase their production? Third question mark: Similarly, an increase could

come from the production of some “stable” countries that in the last years have

decided to expand their oil production, but how much will they increase their

production?

Moreover, cartels are prone to cheating. Right now

Saudi Arabia does not want to cut production because it knows very well that

some other OPEC members will agree on that on paper, but then they will act as

free-riders continuing to produce as many barrels as before. In practice,

Riyadh does not want to increase the world oil prices reducing its own revenues

but in practice subsidizing those of some other OPEC member countries. If

coordination is already difficult to reach within OPEC, much more difficult is

to find an agreement including OPEC members and non-OPEC oil-producing countries.

It is a very complex task. But, it’s evident that without cooperation among the

producers there will always be volatile highs and lows with the related

financial distress. We can call it a purely market-driven “screeching

rebalancing” instead of a cooperative game.

THE SCARY PROBLEM FOR MANY OIL-PRODUCING COUNTRIES: A REAL ECONOMIC COLLAPSE

What is currently happening out there, in the oil

markets, is an economic war between Saudi Arabia and some other sheikdoms of

the Persian Gulf on the one side, and the U.S. shale producers, but also Iran

(an OPEC member) and Russia, on the other side. Some of these players, such as

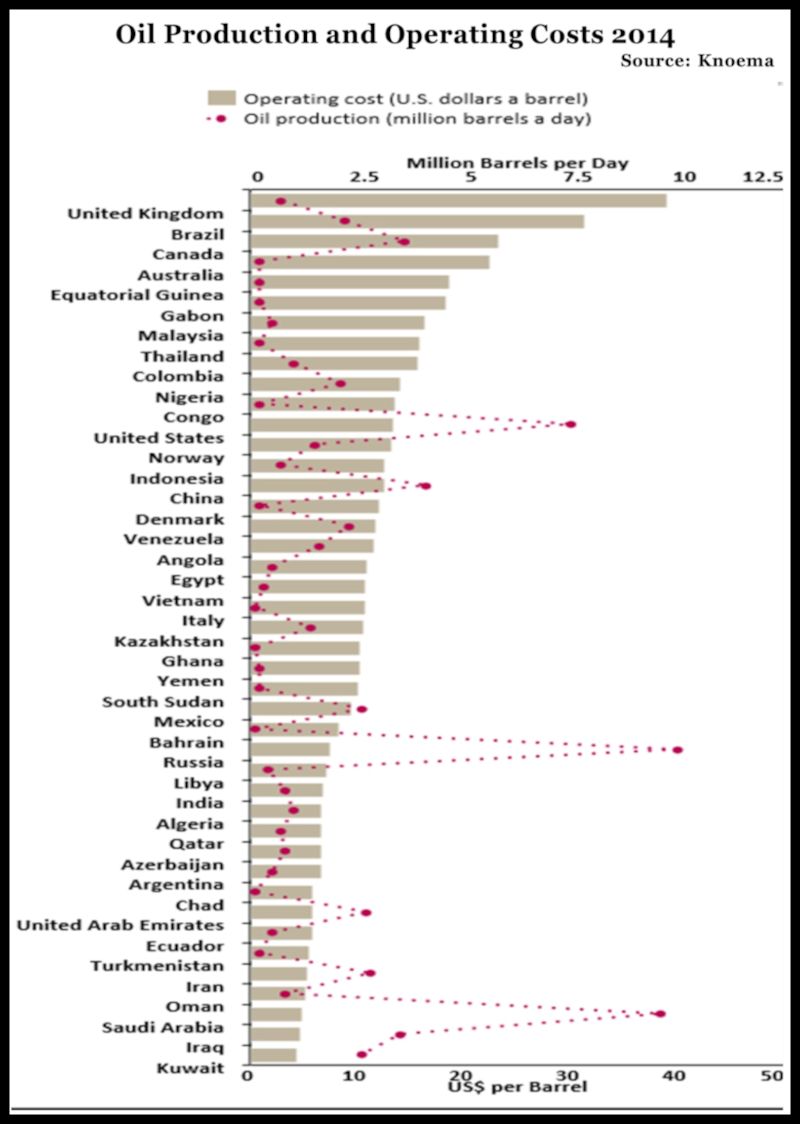

Saudi Arabia, have a lot of ammo, other don’t. A simple look at the following

two pictures, the first one showing the operating costs for crude oil

extraction and the second one the required crude oil price in order to balance the

fiscal budget, put well in evidence the risk of economic collapse that many oil-producing countries might face.

Many oil-producing countries have very low operating costs, but then they need very high crude oil prices in order to balance their budgets. In light of the considerations expressed above in the analysis, it is difficult to imagine oil prices to rebound soon to levels permitting many of these countries to balance their budgets. These are really frightening prospects because the economic sector of countries such as Iraq proper, the K.R.G., Bahrain, Libya, Russia, Nigeria and Venezuela is in completely dire conditions. Because in many parts of the MENA region the situation is already very challenging with 4 armed conflicts (Libya, Syria, Iraq and Yemen) going on, scarce economic resources will add to the present chaos destabilizing even more these fragile countries. And destabilization and poverty mean that fighting the Islamic State will be more difficult, that more people will try to move to other continents (primarily to Europe) and that there will be a wide area of instability on the world chessboard. This situation is in practice a time bomb.