INTRODUCTION

Kuwait

is worldwide known as an oil exporting country. At the beginning of 2011, within its territorial boundaries, Kuwait

owned an estimated 101.5 billion barrels (BBL)

of proven oil reserves equal to around 7 percent of the world's total oil reserves. In addition to these reserves, the country has other reserves located in the

Partitioned Neutral Zone (P.N.Z.), which is an area shared on a 50-to-50 basis

with neighboring Saudi Arabia. This neutral zone should contain at least 5 BBL of

proven oil reserves. The reserves within Kuwait's territory plus the reserves in the P.N.Z. should be equal to about 104 BBL[i].

The

country is a member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC),

and it exports the fourth largest volume of oil within the 12-member

organization[ii].

Petroleum exporting revenues account for around 50 percent of its overall gross

domestic product (G.D.P.), 95 percent of total export earnings, and 95 percent of

government revenues. Kuwait’s economic performance largely correlates to the

oil sector, and its economy is one of the least diversified within the Gulf

Cooperation Council (G.C.C.)[iii].

In other words, up to now talking about Kuwait has meant talking almost

exclusively about oil. Something is now changing.

As

Middle Eastern economies—with a particular attention given to G.C.C.

countries—develop and grow at a consistent rate, they need to have rising

quantities of natural gas. In fact, gas is the ordinary feedstock for power

generation, water desalination, and other energy-hungry industries, such as aluminum, steel, cooling, petrochemical, and construction. Apart from Qatar—which

stands in third position in the ranking of natural gas proved reserves at the world level—all

the other five G.C.C. members are currently experiencing gas shortages (Oman

included). Considering that the Middle East is home to 40.5 percent of the world's proven

natural gas reserves (including 15.8 percent belonging to Iran, a country also experiencing the same problems)[iv], the current gas shortages are a real paradox and they suggest that the Middle

East's share of natural gas resources is relatively undeveloped.

Kuwait's

gas reserves are proportionally not so large as the country's oil reserves, but with 1.8 trillion cubic meters (most of which is associated gas), or 1

percent of the world's natural gas reserves, the country should be in the position of

avoiding importing natural gas. Instead, natural gas—being mainly associated gas—in

Kuwait has always been considered a problem for the oil sector, a trouble when

extracting crude. In practice, associated natural gas has primarily ended up being flared or

burnt when extracting oil.

Since

2009, Kuwait has been obliged to import natural gas in order to reduce recurring

electricity outages, especially during the summer season (from April to October) when

electricity demand springs up. What is interesting to understand is the real

changeover in dealing with gas in Kuwait. In fact, natural gas is not considered any longer a disgrace

when it's pumped out of the ground together with crude oil. Moreover, Kuwait has recently initiated a

spending spree worth $90 billion, which is aimed at expanding both the upstream and

downstream sectors. This spending spree should increase oil production capacity

to four million barrels per day (MMBO/d) by 2020 from 2.5 MMBO/d in 2010. In

Kuwait, given the presence of associated gas in crude oil fields, increasing

oil production means increasing the output of gas. But, despite this increase, numbers say that continuing

to rely on associated gas will not be sufficient, so Kuwaiti authorities are

propping up the exploration for additional gas reserves in order to satisfy the

country's ever-increasing natural gas needs.

Summing

up, although augmenting the output of crude oil by 2020 will increase natural gas production, natural gas imports

are expected to continue until the country is really able to boost its

production of natural gas from gas fields located in northern Kuwait and

offshore along Kuwait's coastline.

CHAPTER 1 — KUWAIT'S ENERGY SECTOR SETUP:

OPENING, CLOSEDOWN AND PARTIAL REOPENING OF THE MARKET

1.1. Kuwait Before the

Oil Age

At the

beginning of 1700, Kuwait was inhabited by nomadic populations from neighboring

territories: Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq. At that time Kuwait was a base for

trade flows between India and Africa. Kuwaiti people became rich merchants. One

century later the most important merchant families decided to hand over the

business of government to an important family, the Al-Sabahs, who were not

involved in trade. This family still holds the power today, and, consequently, the

current emir, Sabah IV Al-Ahmad

Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, is one of its members. This relationship between the

ruling family and the merchant families is at the foundation of the Kuwaiti state

and until today it has been at the cornerstone of the country's politics.

In

1899, Kuwait—both the then emir and the merchant families agreed on this—signed a treaty with the United Kingdom (U.K.). On the Kuwaiti

side, the idea was to get protection from the Ottoman Empire, while, on the U.K. side, the idea was to counterbalance the expansion of German influence in the Persian Gulf

(in those years it was proposed the construction of the Berlin-Baghdad

railroad). In practice, Britain obtained the control of Kuwait's foreign policy

in exchange for protection and for an annual subsidy.

At the

beginning of 1900, the desert country was relying mainly on fishing pearls,

shipbuilding, and trading merchandises between India and Africa. Kuwaitis were about 70,000 and the majority of them used to live in Kuwait City, a trading

center. Given the harsh weather conditions, agriculture was poorly developed, and

most food and water had to be imported.

Things

changed dramatically for the worse in the 1930s when pearl fishing was not any longer a relevant source of income. In fact, the Japanese entrepreneur Mikimoto

had developed cultivated pearls, which started replacing Gulf's natural pearls.

1.2.

The Creation of the Kuwait Oil Company (K.O.C.)

Given

the dire economic conditions, the only hope was to get some financing from oil concessions to foreign oil companies as it was happening in Iran and Iraq. The then emir, Sheik Ahmed (1921-50), could see the example of Bahrain where oil was

discovered in 1932, but at his disappointment the English seemed not too much

interested in Kuwait. At that time, the U.K. Anglo Persian Oil Company (A.P.O.C.)

was already badly economically exposed in both Iran and

Iraq and was not thinking of investing additional resources also in Kuwait.

The American company Gulf Oil was quite interested into Kuwait, but the British authorities claimed Kuwait as a territory under their exclusivity

right. After Gulf Oil's strong protests with the Department of State, in April

1932, the Foreign Office communicated to the Americans that the U.K. was

renouncing to its exclusivity right. But

when the following month (May 1932) oil was discovered in Bahrain, A.P.O.C.

changed immediately its plans. Strategically A.P.O.C. wanted to avoid what

previously had happened in Saudi Arabia where the British company had lost positions in

favor of the Americans.

This

was the best outcome for Sheik Ahmed: Two groups were competing for the

same territory. So, it started a year and a half of bids and counterbids between

the two oil groups. In the end, A.P.O.C. understood that the bidding game with

Gulf Oil was too expensive a negotiation for a territory where oil had still to

be discovered. The best solution was to find an agreement with Gulf Oil. So, in

December 1933, the Kuwait Oil Company (K.O.C.) was created. This was a 50 percent joint

venture between A.P.O.C. and Gulf Oil. The first step was over. Now, it was

necessary to negotiate the concession price with Sheik Ahmed.

The joint venture between

the British and the Americans was absolutely bad news for Kuwait. An agreement

between the two companies was really depriving Sheik Ahmed of his most powerful

contracting tool, an auction. Notwithstanding this, Kuwait was very capable of

understanding and then utilizing the experiences of the oil concessions

previously assigned in Iraq, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. In fact, the negotiation for the

concession was tough[v]

and was over only after a year, in December 1934. K.O.C. got a 75-year oil

concession for the whole territory of Kuwait. Sheik Ahmed obtained an initial

payment, worth 450,000 rupees (£35,000); a guaranteed minimum annual payment of

95,000 rupees (£7,150) until oil

discovery; and then, as soon as oil was extracted for commercialization, a

minimum amount of 250,000 rupees (£18,800) in royalties. In practice, K.O.C.

would pay $0.13 a barrel[vi]

and it got full ownership of petroleum and derivative products from onshore

Kuwait, all Kuwaiti islands, and the territorial waters.

Oil was

then discovered in 1938, and in a few years the economic conditions of Kuwait improved consistently. In 1961, Kuwait had a population of 320,000 people, of

whom 50 percent were nationals with one of the world's highest per capita

income. Kuwaiti people received free healthcare, education, and many other

additional services. After the discovery of oil, the risk connected with oil

explorations abased, and it emerged that a good portion of the Gulf area was

very profitable in relation to oil exploitation. Then, in the 1950s, Middle East

countries started to ask for improved stakes in the oil business. For

example, in Kuwait state participation was required when releasing small concessions

to Aminoil in 1948 and to the Arabian Oil Company (A.O.C.) in 1959.

However, the

real turning point was in 1951 when K.O.C. modified its concession with the state

of Kuwait on the basis of a 50/50 agreement, which meant that from then on

Kuwait would get half of the profits. In addition to this, K.O.C. prolonged the duration

of its concession by 17 years. Worldwide, the relations between owners of energy

resources (such as oil and gas) and international oil companies (I.O.C.s) were

changing. In those years, Venezuela moved away from a concession regime to

profit sharing agreements (P.S.A.s). Nationalization winds were blowing on the

concession regime still applied in the energy sector.

From

the 1960s, it emerged a confrontation between the emir and the government on one

side and the National Assembly/Parliament—composed mainly by members of the most

relevant merchant families and the tribal leaders—on the other side. This

confrontation is still alive today. In fact, the National Assembly/Parliament

has always been a powerful institution, and it has fundamental value in order to

address all major political, economic, and social transformations in Kuwait.

Accepting the nationalization doctrine, the Parliament espoused the

nationalization process of Kuwaiti commodities: oil and gas.

The Constitution

of 1962 reflects the changed atmosphere in dealing with the management of

natural resources. The National Assembly's effort brought in the inclusion in

the Constitution of Article No. 21 and Article No. 152, which directly affirm

that the state owns and controls all oil resources. The National Assembly put

inside the Constitution these two articles in order to have two obstacles to an

easy involvement of I.O.C.s in the Kuwaiti oil and gas sector.

On the

one hand, since 1962, the members of the National Assembly have been

interpreting articles 21 and 152 in a very strict and literal manner, i.e., any

agreement concerning natural resources needs the approval of the Parliament. On

the other hand, the government and the public holding company controlling the

Kuwaiti oil and gas sector, the Kuwait Petroleum Corporation (K.P.C., see: Chapter

1.4: The 1975 Complete Nationalization of the Energy Sector, Oil Included) have

been interpreting Article 152 more openly meaning that Parliament is

supposed to approve only new concessionary agreements and not operating service

agreements (O.S.A.s). After continued disagreements between the two positions with reference to the

correct interpretation of Article 152, the case might be referred to the Constitutional

Court, which has the final word about constitutional interpretations.

It goes

by itself that it is a very delicate argument and that the government does not

want to have a confrontation with Parliament to be ruled by the Constitutional

Court. A Constitutional Court's ruling in favor of Parliament could in fact

be very dangerous for the Kuwaiti political environment[vii].

1.3.

The Nationalization of Kuwait's Natural Gas

From

the 1960s onward, the National Assembly did not accept K.O.C.'s practice of

flaring off the natural gas released when extracting crude oil. It's quite

normal to get associated gas when extracting oil, and in many oil fields it's

exactly the gas pressure to push oil toward the surface. Associated gas can

exist separated from the crude oil in the underground formation or dissolved

in the crude oil. The release of natural gas when producing crude oil is

dangerous because gas may explode. In general, there are four solutions for

getting rid of this problem:

- Flare the obtained gas in a controlled manner (easy to accomplished)

- Commercialize and subsequently sell the gas in a near market (the proximity of

a market was a fundamental element especially in the past)

- Reinject the gas back into the reservoir in order to maintain constant the

pressure of the oil well (this procedure is both complicate and expensive)

- Stop

producing crude oil (economically the worst scenario)

In

Kuwait, following economic considerations (and because the task was easier) K.O.C.

chose to flare gas. And every day several million cubic feet of gas (MMCFG) were

flared. For the National Assembly—but it would be correct to say for the

public at large—flaring gas was absolutely wrong because it held back Kuwait from

having a feedstock that is fundamental for electric power generation and desalinization.

The issue of gas utilization started to be discussed in Parliament in 1969.

The government was reluctant to discuss this topic with I.O.C.s, but it was

under attack by Parliament, which was calling for the full nationalization of

natural gas.

After a

couple of years, in July 1971, the Kuwaiti minister of oil and gas had a

meeting in London with the executives of British Petroleum (BP, previously A.P.O.C.)

and Gulf. The minister carefully explained that the government absolutely

wanted to avoid a full-scale confrontation with Parliament in relation to

gas and that a solution was needed. And with no available solution, the only viable

alternative was the nationalization of gas. The meeting was a failure and the proposal

did not get sufficient consideration by the two companies, which denied the

Kuwaiti Parliament its actual influence over the country's politics. When on

October 28, 1971, the Kuwaiti Parliament reconvened after the summer break, gas

nationalization was the moment's hot topic. Then, by order of Parliament

the gas industry was de facto

nationalized. The result of the nationalization was a relevant increase in the

utilization of gas[viii].

1.4. The 1975 Complete Nationalization of

the Energy Sector, Oil Included

Nationalization

winds were already blowing over the MENA region, and, by then, oil was becoming a

nationalistic tool used to shape domestic and international politics. In May

1962, K.O.C. spontaneously renounced the concession rights with reference to half

the initial concession. The renounced area was assigned to the Kuwait National

Petroleum Company (K.N.P.C.), a company established in 1960. Its shareholders were

60 percent public and 40 percent private. In addition to this, the company had

the monopoly for the distribution of oil products within Kuwait.

The

traditional system of oil concessions was changing toward two extremes: pure

nationalization, supported by the Arab League, and participation supported by

some Arab technocrats. The first real nationalization happened in Libya in

December 1971 (not considering the minor one that occurred in Algeria in 1967). Other

nationalizations followed in Algeria, Venezuela and Iraq.

Completely

different was the strategy of participation

followed by another group of countries led by Saudi Arabia and including Abu

Dhabi, Kuwait, Qatar, Iran and in part Iraq. According to the pragmatic

philosophy of Yamani [Saudi Arabia's oil minister Zaki Yamani], their aim was

to take control of the oil industry gradually

without threatening the stability of the markets and taking into account the

time needed to acquire full awareness of its operating mechanisms. This

strategy coincided precisely with the wishes of the western companies[ix].

In

January 1973, the Kuwaiti government approved the General Participation

Agreement championed and negotiated in New York City by Oil Minister Zaki

Yamani of Saudi Arabia on behalf also of the other Arab countries. According to

this agreement, the companies agreed to hand over a growing share of their

businesses: They started with 25 percent in 1973 to reach 51 percent in 1981.

In other words, K.O.C.'s 25 percent had to be nationalized immediately after compensation equal to the book value of the to-be-nationalized infrastructures.

Within 1982, the Kuwaiti government would get the majority of the company's

shares.

Kuwait's

National Assembly refused ratifying the agreement claiming that it was

necessary to nationalize immediately the whole company, and it accused the government

to be too much subservient to K.O.C.'s owners British Petroleum and Gulf.

Limited trust between the National Assembly and the government would be a

constant element of their relation during the coming decades, and it is still so

today.

In the

summer of 1973, Kuwait announced the intention of renegotiating its

participation quota in K.O.C. with the aim of getting the majority of its capital

immediately. In September 1973, Kuwait hosted the 11th meeting of the Organization

of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (Oapec, not to be confused with OPEC) and

the nationalization principle was approved. Then, following the October 1973

Yom Kippur War, events moved forward very fast. Oil and Finance Minister Abdal

Rahman Atiqui met with K.O.C.'s officials in order to renegotiate the shareholders'

quotas. The minister asked for obtaining 50 percent of K.O.C.'s shares, but later this

agreement did not satisfy Parliament. Then, in January 1974, the minister

reached an agreement for 60 percent of the company and Parliament ratified

this agreement the following May. BP and Gulf received compensation of $112

million according to the value of the nationalized infrastructures.

After

the parliamentary elections of January 25, 1975, the opposition party strongly

criticized the energy policy of the government; this policy was considered too much in

line with the interest of Big Oil and the United States. After these tensions, in

March 1975, the new Kuwaiti oil minister, Mr. Abdul Mutallab Al Kazemi, announced the intention of nationalizing the remaining 40 percent of the shares still in the hands of the BP-Gulf joint

venture[x].

The two companies opposed such a move underlining that they literally

had helped Kuwait to set up its energy sector. Their attempts were to no

avail and did not reverse the trend toward the nationalization. And in specific,

nationalizing the commodities was considered by Arab countries an act of

sovereignty. BP and Gulf demanded a $2 billion's worth compensation, but in the end, they got only $50 million. Similarly, for them it was not possible to get

Kuwaiti crude at a preferential price from then onward.

The

following steps were the "Kuwaitization" of K.O.C.'s personnel and the

nationalization of K.N.P.C. The entire oil sector was under the control of the

Supreme Petroleum Council (S.P.C., headed by the prime minister), which had been

established thanks to Decree for

Establishing the Supreme Petroleum Council of August 26, 1974. The basic idea

behind the institution of the council was to have an institution for drawing

the general policy of petroleum wealth within the framework of the national

economic and social development plan.

Later,

on January 27, 1980, it was created the 100-percent government-owned Kuwait

Petroleum Corporation (K.P.C.), which is Kuwait's national oil company. It's based

in Kuwait City, and it's an umbrella company incorporating several fully owned

subsidiaries. K.P.C. manages domestic and foreign oil and gas reserves. Some of

its subsidiaries, like K.N.P.C. (Kuwait National Petroleum Company), Petrochemicals

Industry Company (P.I.C.) and Kuwait Oil Company (K.O.C.)[xi]

had been created in the 1960s by the state together with private investors. By

1980, thanks to Law No. 6 of 1980 (establishing K.P.C.) they all were transferred

to K.P.C.'s full ownership.

Finally,

in 1986 the Ministry of Oil was established as separate from the Ministry of

Commerce and Industry, and it started to have policy-making powers in

conjunction with S.P.C. In specific, since then, the minister has been given a supervisory

role over all public institutions related to the oil and gas sectors.

1.5. Recent Years' Attempts Aimed at

Reversing the Complete Nationalization of the Energy Sector (Oil and Gas)—The

Kuwait Project

Thanks to the

nationalizations of natural gas in 1971 and of oil in 1975, Kuwait's energy

sector was totally nationalized, and no I.O.C. was allowed to operate in the

country any longer. During the nationalization period, the only I.O.C. that had (and still

runs this activity today) business relations with Kuwait was America's Chevron,

which had operations onshore in the so-called partitioned neutral zone between

Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

In this area, Saudi

Arabian Chevron Inc. and K.O.C. explore for and produce oil and gas. The energy

production from this area is shared between the two countries.

Nowadays, although with

great difficulties for the I.O.C.s, it's possible to operate in Kuwait through

service agreements (S.A.s). In practice, in the MENA region Saudi Arabia's

energy sector is the only one that is still totally close today to foreign

companies (in reality, Saudi Arabia has attempted to find more natural gas

by allowing I.O.C.s a partial access, which it does not permit in the oil sector

where Saudi Aramco rules). The table above showed the current different

approaches to energy contracts in the MENA region.

In 1975, the

nationalized K.O.C. had advanced technological skills and was by that time

capable of extracting crude oil without the assistance of I.O.C.s. This was

possible because in general Kuwait's oil fields—among them there is Burgan,

the second largest oil field in the world (it started production in 1938)—are easy to operate. In 1975, the on-production crude oil fields were

onshore, at an early stage of development and with high underground pressure.

In practice, it was necessary just to drill vertically wells (between 3,500 to

5,000 feet) and then oil would flow to surface. By 1990, K.P.C. was the only Third

World's state-owned company capable of selling its oil using its own brand name

and through its own service stations. These results were an important milestone

for Kuwait.

The

full shutting down of the oil and gas sector to I.O.C.s had lasted for 15 years,

when practically the course of events was changed by the First Gulf War (August

1990-February 1991). Since the liberation of Kuwait in 1991, it appeared clear

that the oil sector was in difficult conditions owing to the ruinous Iraqi

invasion. K.P.C. immediately looked for technical assistance from I.O.C.s and there

was a tacit understanding that once the oil industry was reconstructed the

upstream sector would be open to the assisting I.O.C.s. Effectively, since 1991

some I.O.C.s have been involved in the upstream sector providing simple technical

assistance. Two years later surfaced the idea of allowing I.O.C.s not only to

provide technical assistance, but also to invest in the upstream sector with reference

to a new-and yet-to-be-developed project called Project Kuwait, which aimed at increasing

oil production capacity from four northern oil fields: Raudhatain, Sabriya,

al-Ratqa and Abdali.

Apart from some general advantages that could be obtained from

the involvement of I.O.C.s (see the above box), one reason emerged above all:

securing military support from abroad. The initiative of developing oil fields

located on the border with Iraq and of requesting the active role of I.O.C.s

was backed by the idea that having foreign workers stationing in the area of

Project Kuwait would facilitate military alliances with the countries to which

belonged the involved I.O.C.s. In this regard, it should be understood that President Saddam

Hussein lost the war, but still held power in Iraq. In practice, Kuwait wanted

to create a sort of economically driven buffer zone making the border area much

safer.

In the

meanwhile, under a 1994 agreement with K.O.C., Chevron subsidiaries provided

technical expertise for the continued development of the Burgan field. This K.O.C.

agreement expired in 2008. In any case, recalling Chevron for service agreements in

relation to Burgan was quite obvious in 1994. In fact, Gulf Oil Corp., which

had become part of Chevron in 1984, had discovered Kuwait's super-giant Burgan field in

1938 and had been working there up to 1975. In practice, it was the Burgan discovery that had

transformed Kuwait into a top oil producer. Another example of technical service

contract was the one awarded in 1994 to Burgan Equipment Co., a private company

based in Kuwait (it's not an I.O.C.). It consisted

of supplying, installing, and commissioning training equipment in the K.P.C.

training center. This service agreement was completed successfully, but, with

reference to Project Kuwait, the 1995 initial proposals from K.P.C. were opposed

by both Parliament and S.P.C.

Then at

the end of the 1990s it appeared clear that Kuwait's oil and gas sector was

behind its production potential. Already there was the need to explore for and

then develop more difficult oil fields—like those located in the northern

part of the country—than the ones that had been pumped for the previous 50

years. On-production crude oil fields were mature so that their internal

pressure was not sufficient to permit an easy oil recovery. Also the giant

Burgan oil field , the cash-cow oil field was at risk of being permanently

damaged. This situation was partly due to a regulatory system banning foreign ownership

of hydrocarbon resources. In short, K.P.C. and its subsidiaries, although trained,

were missing the skills for working oil and gas out of difficult fields. It was

a too big bet for K.O.C. to work alone. Given the infancy of its ability in harnessing top-notch technologies, it was uneconomically for K.O.C. to assume

full risk in completely handling new difficult oil fields.

Finally,

the S.P.C. made the appropriate decision in 1997 and understood

the non-procrastinating necessity to open the oil and gas sector to I.O.C.s. The

plan was to invite selected I.O.C.s (Chevron, Conoco, ExxonMobil, Total, Shell,

BP and ENI) to participate in the development of oil fields located in north

and western Kuwait. Technically, the substantial change happened in March 2001 when the

National Assembly passed Law No. 8 Foreign Direct Capital Investment Law of

2001, which partially facilitated some foreign direct investments (F.D.I.s) in

the Kuwaiti energy sector. In fact, according to Article No. 3 of the law (and

to the explanatory memorandum to the law) the procedure for foreign investments

in natural resources is now permitted, although not with a simple license as it happens

in other sectors, but only pursuant to a law and for a limited period of time.

In other words, Parliament needs to know and approve every contract that is

going to be subscribed between K.P.C. and any I.O.C.

The target

of this complex procedure is preventing corruption and ensuring transparency in

investment practices. This law spurred one more time a lot of debate given the

different mindsets in relations to the energy sector: opening (although through

just service agreements) or closure to I.O.C.s. However, after this law, K.P.C.

announced reinvigorated plans to permit foreign companies to develop the oil

fields located in north Kuwait. In the end, this law proved useful to implement

improved service agreements although it took nine years before the signature of the

first of these contracts with an I.O.C.

And in relation

to the development of the oil fields located in north Kuwait, swiftly K.P.C.

started lobbying in favor of modifying Kuwait's oil and gas sector regulatory

regime asking for permitting the I.O.C.s to participate in the oil industry through

operating service agreements (O.S.A.s).

According to K.P.C., three principles should govern the relationship between Kuwait and I.O.C.s:

- O.S.A.s should be consistent with Kuwait's Constitution

- Kuwait should have the ownership of all the produced oil and gas and the obtained

revenues

- I.O.C.s

should not get any ownership title over crude oil and gas

The

draft legislation regarding O.S.A.s (they were planned to have duration of 25

years) was introduced in Parliament in 2003. In order to get I.O.C.s'

investment, it was established an incentivized buy-back contract (I.B.B.C.) neither

implying a P.S.A nor implying a concession. O.S.A.s, i.e., the operating services

agreements would in detail define I.O.C.s' position.

According

to this draft, Kuwait would have sovereign control over the production and would

manage the strategic side, while I.O.C.s would control the operational

management providing for services and construction primarily on a contractual

basis.

I.O.C.s

would be remunerated for 50 percent of the operating costs on a monthly basis and

for 50 percent of the capital costs over a 10-year period. The I.O.C. compensation would

be based on a variety of fees (an old oil fee to be paid on production that

could be produced by K.O.C., an oil fee to be paid on production over the old oil

curve, a gas fee, an allowance for recovering the invested capital, and another

allowance for annual capital investments) with the aim of covering costs,

incentivizing a positive behavior, and rewarding the obtained results. According

to the draft, there was also the idea of permitting foreign investors to

transfer their O.S.A.s to another foreign investor, to repatriate capital and

profits, and to be entitled to compensation in the case of a takeover by the state.

Violating

the terms of an O.S.A.—at least as prescribed by the draft legislation—would include an initial warning, the withdrawal from the investment, and, at

last, the liquidation of the investment.

The

proposed relationship between Kuwait and I.O.C.s in the Kuwait Project is the

natural evolution from what we have today. It is this second phase of our

relation that takes into account the strengths and limitations of the existing

relation. The Kuwait Project proposes to expand I.O.C.s role from an advisory role

to a fields' management and operation role, where I.O.C.s will act as a super

contractor under the guidance and strategic management of the state. ... In

essence, Kuwait requires the type of relationship with I.O.C.s, which is primarily

based on operating services where I.O.C.s are paid a fee per bbl of oil produced.[xii]

In

2005, the Financial and Economic Affairs Committee of Parliament issued a

favorable report about the draft, but in the same year the State Audit Bureau

expressed reservations about the constitutionality of the legislation. After

the issue was raised the committee withdrew its report espousing the

unconstitutionality of the draft law.

The problem

was in the fact that for the government there was no need to have a specific

law authorizing a specific I.O.C. to work in Kuwait under a service agreement, while for Parliament a case-by-case law was required (different

interpretation of Article No. 152 of the Kuwaiti Constitution). The government

considered that there were the numbers for approving the draft law in

Parliament, but it postponed the vote to early 2006. In January 2006, Emir Jaber III al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah died

and the new emir, Sheikh Sabah IV

Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, after an increasing confrontation between

Parliament and the government dissolved the former. Since then the relations

between Parliament and government have been very tense with the former accusing

many ministries (including the ministry of oil) of corruption.[xiii]

In 2007, the situation was still totally frozen in relation to the legislation concerning

the energy sector, so the emir expressly conceded to Parliament the power to approve every I.B.B.C. related to Project Kuwait. However, such a move did not prove to be good

for speeding up the project because Parliament continued delaying it. And,

given the difficulties to get some I.O.C.s to work in relation to Project Kuwait until a

couple of years ago there was the idea that neither an improved version of T.S.A.s

nor O.S.A.s could ever materialize in Kuwait.

In this

regard, it needs to be pointed out that I.O.C.s' country managers were (and

probably still are) not convinced about the attractiveness of the offered

contractual terms and, even if the draft law were approved, there would be the

risk that all I.O.C.s might decline to bid. Plus, maintaining relations with

counterparts like the oil minister, K.P.C. and K.P.C.'s related subsidiaries' C.E.O.s,

who serve for very short terms, is an additional hurdle. In 2009, Chevron and

BP, which had been assisting Kuwait since post-First Gulf War reconstruction,

finally withdrew their senior executives after giving up on finalizing an

agreement.

1.6. The Current Contracts for I.O.C.s:

Enhanced Technical Service Agreements (E.T.S.A.s) for Both the Oil and the Gas

Sectors.

Given

the mentioned stalemate with no real progress for Project Kuwait, in the last

years both K.P.C.'s and I.O.C.s' managers have been pursuing as a viable

alternative, the so-called enhanced technical service agreements (E.T.S.A.s). Not

implying any level of foreign control over oil and gas (absence of any bookable

reserves)[xiv],

these agreements are not equivalent to O.S.A.s, while they still are one step

ahead than the normal T.S.A.s. In fact, with E.T.S.A.s Kuwait would pay premium prices to have I.O.C.s'

engineers assigned as long-term consultants to K.O.C. Moreover, high fixed fees

would be coupled by variable performance-based payments related to the achievement

of production targets. E.T.S.A.s are a hybrid between P.S.A.s and traditional T.S.A.s.

In the end, E.T.S.A.s would incentivize international companies to increase

their scope and level of involvement in upstream activities obtaining at the

same time more supervisory authority.

However, the real advantage of E.T.S.A.s lies in not requiring any approval by Parliament

although it's clear that they could still spark a loud political debate as a

result of the magnitude of the paid fees and the size of the I.O.C.'s

footprint. It's evident that the continued power struggle between Parliament

(protecting its right to legislate) and the government (feeling itself too much

bound by Parliament's consent) is not helping also the implementation of E.T.S.A.s as well.

And the State Audit Bureau is suspicious about why the government is paying ten

times as much for an E.T.S.A. as for a usual T.S.A.

All

this said, E.T.S.A.s are not a universal remedy for the current stalemate. In

fact, I.O.C.s are less enthusiast about this kind of contracts than about the

planned O.S.A.s, formerly targeted at Project Kuwait. Given the not quite appealing contractual conditions, there is also the

possible danger that I.O.C.s

may be tempted to maximize short-term returns (like for instance maximizing

production) versus a more strategically oriented business plan. I.O.C.s

consider E.T.S.A.s a viable option as long as the received fees are able to cover

their costs (also with no profit at all). With E.T.S.A.s energy companies would carry out the same role that they have when they sign T.S.A.s. In practice, the interested companies would

sign E.T.S.A.s just for having a working relation with K.O.C. Thanks

to these agreements, the companies would be well positioned at the government

level and it could it be possible in the future to be awarded an O.S.A. Fees—I.O.C.s would also be interested into

getting production incentives—should cover at least the costs, otherwise there is no real

interest into entering a market for simply losing economic resources.

Another

unclear point is whether E.T.S.A.s can be a consistent substitute for O.S.A.s

and can permit also the implementation of Project Kuwait. However, again the kernel

of the issues rotates all around the necessity of tracing a fair balance

between K.P.C. on the one side, and I.O.C.s on the other side. The correct

incentive—also with E.T.S.A.s—could permit I.O.C.s to be focused on the

long term and on technological quality.

Finally,

in February 2010, Shell signed an E.T.S.A. to exploit some 2005-06 oil

discoveries (20 BBL to 25 BBL of heavy and sour oil) in the Sabriya and Umm Niqa areas

in northern Kuwait. Currently, this project is proceeding slowly. Similarly, in

August 2010, still in northern Kuwait, British Petrofac signed another E.T.S.A.

with K.O.C. in order to boost production capacity in the Raudhatain and Sabriya oil

fields.

The

future move will be either maintaining the status

quo (remaining within the E.T.S.A. contractual scheme) or developing an

eventual and alternative type of agreement between K.P.C. and I.O.C.s. There is no

silver lining if a fair balance isn't established between Kuwait on the one

side, and I.O.C.s on the other side. In this regard, a good example comes from

Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan (a semiautonomous region of Iraq). In fact, while Baghdad does

offer just service contracts with low fixed earnings, in Iraqi Kurdistan there are

already on offer production sharing contracts with their fairer profit share

for I.O.C.s. It goes by itself that I.O.C.s are at present reaping service

contracts in Iraq only under the auspices of getting improved and fairer

contracts in the future, while the attractive and interesting Iraqi Kurdistan

contracts are hampered by the bickering between Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan on how to

divide hydrocarbon riches.

Moreover,

it is worth underlining that Kuwait's population, who is accustomed to a high

standard of living from cradle to grave thanks to an ever-present welfare where

the state fully covers some priority costs (healthcare, housing, and education)

and subsidizes some secondary costs (fuel, electricity, and water), does not

identify any real and urgent economic needs to allow I.O.C.s to work in Kuwait

under different terms and with an increased operational role. The majority of

the population deems Kuwait's commodities to be integral part of Kuwaitis' national

patrimony, which has to continue staying in Kuwait's hands.

Summing

up, today's private role in Kuwait's oil and gas sector is limited to

contracts relating to providing at maximum E.T.S.A.s at the upstream level.

Political disputes between a royally appointed prime minister and the partially

elected Parliament are stalling possible and necessary reforms.

1.7. Organizational

Structure of Kuwait's Energy Sector. No Differentiation Between Oil and Gas Companies

In

1980 it

was created the 100-percent government-owned Kuwait Petroleum Corporation

(K.P.C.), which is Kuwait's national oil company owing all the national oil and

gas reserves. Based in Kuwait City, K.P.C. has a network of fully owned

subsidiaries covering several different activities within the oil and gas sector:

exploration, refining, oilfield services, product shipping, and petrochemicals.

The table below shows the structure of the oil and gas industry in Kuwait with

the specific role performed by each of the K.P.C. subsidiaries.

In

Kuwait there aren't different companies—while belonging to the same holding—that deal only with gas or only with crude oil. In 1938, oil was discovered and

since then the country had been producing only crude oil up to the beginning of

1970s when the recovery of associated natural gas was added to crude oil

production. In other words, there is no single subsidiary dealing only with gas

or only with oil as is for instance the case in Qatar with Qatar Petroleum dealing

with oil and Qatargas dealing with gas.

CHAPTER 2 — ANALYSIS OF KUWAIT'S NATURAL

GAS SECTOR

2.1. Natural Gas Reserves and the

Development of the Middle East's Gas Industry

Since

last century, the Middle East area has been deemed as one of the key regions

for oil and gas. The table below shows the ranking of the first twenty-five countries according

to the world's proven natural gas reserves. It immediately stands out that

Iran, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, U.A.E., Iraq and Kuwait, are respectively in second,

third, fourth, seventh, eleventh and twenty-first position. Together, their

share of proven natural gas reserves amounts to a staggering 39.5 percent. The

share of the six G.C.C. countries is equal to 22.5 percent.

These

numbers should suggest that the Middle East has a huge quantity of available

natural gas (apart from Qatar's, much of this gas consists of associated reserves,

and for OPEC members this means that the production is restricted by OPEC

quotas) and that gas shortages should be practically a nonsense.

On the

opposite, in the last five years, many Middle Eastern countries have been

experiencing gas shortages with all the subsequent bad economic outcomes. With

the exception of Qatar, the natural gas industry in the Middle East has always

been considered less important than the oil industry. While petroleum was

getting powerful investments, natural gas was developed with poor economic

resources (not to mention that at the beginning of the oil industry associated

gas was flared or burnt), lacking storing and transporting infrastructures and following

an almost inexistent regulatory framework. Behind this absence of investments

there was probably throughout all countries the practice of maintaining low domestic

gas prices (subsidized prices introducing market distortions). Without any

incentive, both private companies and governments were not much inclined toward

pouring in resources for natural gas exploration, production, and

infrastructure. Moreover, in order to develop the natural gas industry many

different factors do need to act toward that end: the political environment, the

presence of the required technology, investments availability, and some

country-specific reasons[xv].

In

today's Middle East, the only countries where natural gas production tops

domestic consumption are Egypt and Qatar[xvi].

These countries are net exporters. The other countries are all experiencing

natural gas shortages. An interesting example is the U.A.E. In five years this

country has moved from being a net exporter to becoming a net importer.

Natural

gas is needed because the Middle East economies (and in specific the G.C.C.

economies) are developing and growing at a very high rate with the

consequence of an ever-increasing demand of natural gas, which is

the main feedstock for electricity generation, water desalination[xvii], and the petrochemical industry (and obviously a number of other industries like

steel and aluminum). Moreover, for power plants the swing toward gas is

supported by its greater efficiency and environmental friendliness in comparison to the utilization of heavy fuel oil or coal.

Given

the current situation, some Middle East countries are already obliged to import

natural gas or to look for alternative energy sources notwithstanding the fact

that globally there is a surplus of natural gas.

Kuwait

is one of the Middle East countries where there is natural gas, but, at the same

time, the industry is underdeveloped. Kuwait's gas resources are in proportion not so large as the country's oil reserves, but with 1.8 trillion cubic meters (the majority of which is

associated gas), or 1 percent of the world's

natural gas reserves, the country should be in the position of being self-sufficient

in relation to its gas necessities, of course if the natural gas industry were well

managed.

In the

last years, relevant discoveries of non-associated natural gas have occurred in north

Kuwait. And I.O.C.s have shown interest for these discoveries. Up to date the

involvement of Big Oil into gas projects in Kuwait has been characterized by

the same two impediments that are present in the oil sector: unattractive

contractual conditions summed to political uncertainties about how managing

Kuwait's oil and gas sector.

In practice in Kuwait there is no

factual shortage of natural gas under the ground (onshore) or the seabed

(offshore), but—and this is the real problem—there is a serious deficiency

in investment and policies to get it out[xviii].

In order to develop Kuwait's still

embryonic natural gas industry and consequently tackling the ever more occurring

gas shortages, today's strategy is

based upon two pillars:

- Exploring and then developing domestic non-associated natural gas fields

- Importing natural gas with different means of transportation

2.2. Gas Exploration and Current Gas Production

According

to E.I.A., in 2010, Kuwait produced 1.17 billion cubic feet per day (BCFG/d)

with an 8 percent increase in comparison to 2009. This gas is mainly associated, and this means that domestic natural gas supplies are directly linked to OPEC's

crude oil production quotas. Pumping out less crude means for Kuwait having at

disposal less natural gas, while the country needs ever-increasing quantity of

gas for generation of electricity, water desalination, the petrochemical

industry, and the enhanced oil recovery (E.O.R.) techniques, which are required

for boosting the rate of oil recovery. In 2010, around 85 percent (1 BCFG/d) of

the overall natural gas production came from associated gas, while

non-associated gas accounted for a quantity of 150 million cubic feet per day

(MMCFG/d) to 200 MMCFG/d.

Up to the 1971 natural gas nationalization, associated gas

in Kuwait had always been considered a problem for the oil sector—a trouble

when extracting crude. In practice, associated natural gas ended up being

flared when extracting oil. Instead, after 1971 natural gas has been employed

as a domestic feedstock in different activities and since then Kuwait has been

consuming ever-increasing quantities of natural gas for the different above-mentioned utilizations.

Dependence

upon gas imports is not a recent phenomenon, but it dates back to at least

20 years ago. In fact, before the 1990 invasion by Iraqi troops, Kuwait was already

becoming dependent on the importation of Iraqi natural gas. Afterward, the 1990

invasion messed up things and, once war was over, this natural gas relation with

Iraq was not doable anymore. In practice, after the liberation, specific plans for

importing natural gas had come to the fore of Kuwait's political debate and in specific

two countries were essentially considered as possible gas suppliers: Qatar and Iran.

Basically, twenty years ago there was the idea of importing natural gas and not

of exploring for domestic non-associated natural gas. At least at the beginning Kuwait was able to

compensate for gas shortages through the availability of cheap fuel for energy

necessities and through naphtha as a petrochemical feedstock. However, as a result of this policy, today's 70 percent of electricity generation in Kuwait derives

from crude oil. K.O.C. has recently announced its intention of reaching a

production target of 4 BCFG/d by 2030. This value is approximately four times as

much the 2010 gas production.

In

order to increase the production of non-associated gas, the first ranked option

is developing gas fields from north Kuwait. Another possibility could be exploring

offshore, but Kuwait's fiscal and political situation does not proactively work

towards this target.

In

2006, it was discovered the Jurassic non-associated gas field, which possesses an

estimated 35 trillion cubic feet of reserves. Preliminary studies completed by

Schlumberger and Shell suggested considering the field one of the most

challenging fields in the world in light of two factors: the geological

composition and the technical complexities. This gas is mostly condensate, plus

it's very sour because it contains high concentrations of toxic and corrosive

hydrogen sulfur. Initially, a first phase projected to obtain 175 MMCF/d of gas and

50,000 bbl/d of condensate by 2008, but it apparently produces only 140 MMCF/d.

The second phase, due on line by 2013, should have a production capacity of 500

MMCF/d and it is implemented by the two companies Kuwait's Kharufi National and

Italy's Saipem. At the beginning, the development plan of the Jurassic field envisaged

a 600 MMCF/d by 2012 and 1 BCF/d with also 350,000 bbl/d of light crude or

condensate by 2015. Experts say that this target is unlikely right now. Anglo–Dutch

Shell is developing the Jurassic gas field thanks to its February 2010 E.T.S.A.

valued at $700 million.

This

deal is currently considered a sort of landmark deal because it is helping to boost

non-associated gas production (and consequently boosting the country's domestic

utilities facilities), but also because it should finally indicate a Kuwaiti

real interest in collaborating with I.O.C.s in order to develop Kuwait's

upstream activity. In specific, if K.P.C. does have some know-how in dealing with

oil, it's really missing the required technical skills for extracting gas and

heavy oil.

Another

possible solution for increasing Kuwait's quantity of non-associated gas is the

Dorra gas field, which is located offshore in the P.N.Z. Three countries are

sharing this field: Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Iran (the latter calls the field, Arash). Kuwait and Saudi Arabia announced plans to start by 2017 a gas

production of 500 MMCF/d to 800 MMCF/d. Until now, Iran has announced that it

would develop by itself its own side of the field. As to the current political

tensions between Arab countries on the one side, and Iran on the other side,

it's highly presumable that the development of this gas field won't be void of

disputes among the neighboring countries.

Increasing

the availability of natural gas does have scarce meaning if contextually Kuwait

isn't expanding its gas processing infrastructure. In this regard, South

Korea's Daelim is constructing Kuwait's fourth gas processing plant with an 800

MMCF/d capacity. This new unit (the largest to date) located on the site of the

Ahmadi refinery is scheduled to increase in 2013 Kuwait's gas processing

capacity to 2.3 BCF/d. A fifth gas processing plant is in the planning stages

and if completed it will expand the overall gas processing potential to more

than 3 BCF/d. All this said, also after completion of the fourth and fifth

trains, Kuwait won't be able to meet the growing levels of its domestic demand.

Realistically,

it is quite likely that Kuwait's gas production will only cater to the

country's domestic needs. In fact, the aggressive exploration program aimed at

expanding non-associated gas reserves (there is optimism about finding

additional reservoirs) is targeted at satisfying domestic needs. K.O.C.'s officials

point out that it's not probable for Kuwait to become a major gas exporter.

Kuwait is only a small-quantity exporter of liquid petroleum gas (L.P.G.)

extracted from natural gas.

2.3. An Ever-Increasing Consumption and the

Necessary Gas Imports

In

2010, Kuwait utilized around 529 BCF of natural gas. This value is equal to

1.45 BCF/d against a production amounting to 1.17 BCF/d (approximately the

gap is about 270 MMCF/d to 280 MMCF/d). Virtually, in 2010, the country

consumed about 24 percent more than the produced quantity. This problem is not

new, but it had emerged also before the 1990 invasion. What is happening

is that since 2008 Kuwait has been unquestionably consuming more natural gas

than it has been producing. The country has experienced in the recent years gas

shortages, which have translated into electricity outages especially during summer

months (April to October). Outages have brought in the shutdown of refinery and

petrochemical operations in order to provide electricity to the population, but

this has resulted in consistent losses for Kuwait's economy. A possible solution—apart from increasing the production of domestic non-associated gas, which in

any case would not be sufficient to cover all consumption needs and

would take several years before being available, while the problem is already a

reality—is importing natural gas.

Gas imports

may be implemented in two ways:

- Through

pipeline or

- As

liquefied natural gas (L.N.G.)

For

Kuwait, pipeline imports mean importing gas from Iran, Iraq, or Qatar. However, this

solution—if it isn't to be ruled out given different political tensions between

neighboring countries—will be implemented only in the medium term. At the end of 2009 beginning of 2010 there had

been some talks about the opportunity of building a 570-kilometer (mainly

submarine) pipeline transporting 3 BCM/y to 4 BCM/y of gas from South Pars gas

field in Iran to the border with Kuwait. At present, this plan is not progressing at

all. According to some analysts, settling eventual disputes with Iran in

relation to the development of the Dorra offshore gas field (non-associated

gas) located off the coast of the P.N.Z. could speed up things with the

pipeline project from South Pars, but in the last twenty years there have been

a lot of discussions with Iran about the construction of pipelines but no

tangible results.

In

the end, the most viable, although expensive solution, for importing gas to

Kuwait is to liquefy it. The country became the second in the region after

Dubai, to turn to L.N.G. imports. This solution is getting more credit especially

after the October 2011 Kuwait's decision of abandoning the development of nuclear

power energy. In fact, Kuwait was supposed to utilize nuclear energy in the

long run. In 2009, it announced the intention of establishing a nuclear

commission and the following year in January 2010 the country announced a

20-year deal with France's Atomic Energy Commission for the development of nuclear

energy in Kuwait[xix]. The

initial plan was to build 4 nuclear power plants by 2022 (one had to be located on

the island of Warba and a second one on the island of Bubiyan, which both have

been reclaimed by Iraq for more than 70 years). Although other regional

countries remain committed to nuclear power plants, it's very difficult for

Kuwait's leaders to proceed with the nuclear program, especially in

consideration of the strong parliamentary opposition to the program.

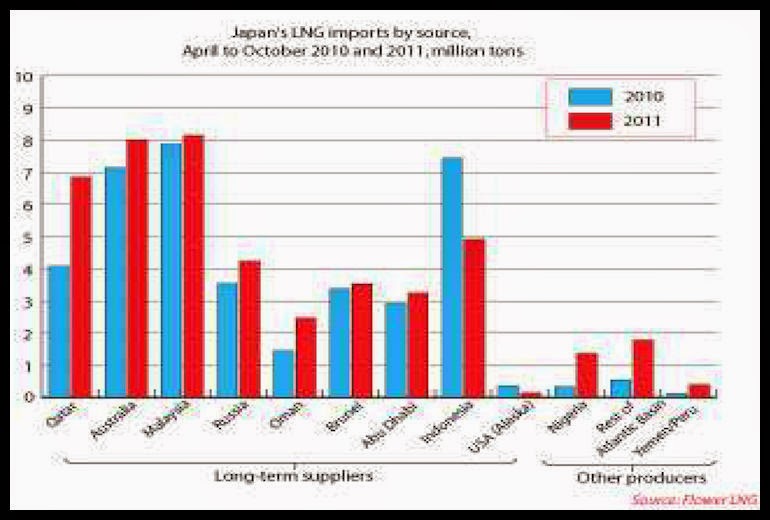

In

2010, Kuwait imported 270 to 280 MMCF/d of L.N.G., which was sourced mainly from

Oman, Egypt, and Trinidad and Tobago. However, the country is also taking re-exports

of L.N.G. from Qatar via Abu Dhabi. This is a direct consequence of the fact

that three years ago Saudi Arabia blocked a projected pipeline from Qatar to

Kuwait.

L.N.G.

gas imports rose from 11 cargoes in 2009 to an estimated 43 to 47 in 2011 (meaning

a 409 percent increase in only two years considering 45 cargoes in 2011). And in

2011, Kuwait will import up to 42 percent more L.N.G. than in the previous year,

having extended the buying period into November.

Natural gas demand is highly

seasonal depending on several factors. Weather conditions, income, demographic

trends, consumer and politicians' preferences, and alternative fuels have all an

impact.

L.N.G.

may be traded thanks to spot contracts (short-term contracts) or medium- to

long-term contracts. Since 2009, Kuwait has been implementing both spot

contracts (the country is probably buying British Gas Group cargoes originating

from Trinidad and Tobago) and medium-term contracts like the 4-year contracts

with Netherlands' Vitol, an energy trader, and Shell. Which price structure

these two typologies of contracts follow when one counterpart is Kuwait is not

clear. While it's presumable that cargeos originating from the Atlantic Basin

may be priced according to that region's pricing structure, for the signed medium-term

contracts there is less transparency. The contracts for L.N.G. shipments signed

with Vitol and Shell do not precise the price to paid. The only released

comment said that costs would be calculated according to delivery criteria and

to a formula linked to crude oil. Both companies could be providing Kuwait with

L.N.G. from a secure portfolio of geographically differentiated options. It

would be interesting to understand how to price intraregional L.N.G. trade (for

instance between two G.C.C. countries) occurring within a less-than-3,000-mile

distance. In fact, 3,000 miles is the minimum distance for economic viability

of the L.N.G. business. Up to now, L.N.G. movements from the Persian Gulf have

been interregional, mainly oriented from the Middle East to Asia and not

intraregional. And when selling to Asian countries the price has been established according

to the Asian L.N.G. market. Currently, only the U.A.E. and Kuwait are importing

L.N.G. Bahrain will begin importing it around 2014 and recent rumors (October

2011) from Oman say that the country could build an import terminal for L.N.G.

to tackle a shortage of fuel, which indeed may impact both Oman's industry and power

generation.

At the beginning of 2009,

Kuwait was in talks with RasGas, a joint venture of Qatar Petroleum (Q.P.) and ExxonMobil.

The negotiations were aimed at signing a long-term deal for the supply of L.N.G. The deal was not finalized because

K.P.C. did not accept the requested price. QatarGas had already secured long-term contracts, so it was not available. Recently, K.P.C. has also been purchasing spot L.N.G. Part of this

spot L.N.G. probably comes from Trinidad and Tobago with a major discount by

British Gas (BG). Shell's QatarGas-IV train was available for serving Kuwait because

this train was originally destined to serve the U.S. market where currently

there is a lot of surplus of domestic gas and consequently prices are low. In

practice, Shell had a surplus, which could be easily diverted toward Kuwait and the

U.A.E. although with no economic convenience on the buyer's side.

And in August 2009, Shell made

its first L.N.G. delivery to K.P.C.'s floating terminal to help meet peak summer

demand. The country uses Excelerate's (an

L.N.G. importing and regasification company) tankers as a floating import

terminal at the Mina Al-Ahmadi gas port (up to 500 MMCF/d of L.N.G.). The following

year, in April 2010, K.P.C. signed two very similar contracts for receiving L.N.G.

for the summer months (April to October) from 2010 to 2013. One was signed with

Vitol, while the second contract was signed with Shell. With these two

agreements K.P.C. wanted to import 2.1 million tons a year of L.N.G. This amount

corresponded to five L.N.G. cargoes per month: three supplied by Shell and two

by Vitol. Thanks to these two deals Kuwait should be able to avoid burning

around 800,000 crude oil barrels per day.

Last April,

Kuwait started some negotiations with Royal Dutch Shell—a company that has

quite well established contractual relations with Kuwait—in order to import L.N.G.

from southern Iraq. Before the First Gulf

War, Iraq had already exported significant volumes of natural gas to Kuwait.

This

gas came from Iraq’s southern Rumaila field through a 40-inch, 100-mile, 300 MMCF/d

pipeline to Kuwait at Ahmadi. This time, Kuwait

is not dealing with the Iraqi government (the Kuwaiti Parliament would block

any deal that put Kuwait directly dependent on Iraq's government) but with an I.O.C.

like Shell. Kuwait would like to implement this project in maximum a year and

a half year, but it's a short timeframe.

In this regard, it should be underlined that only in

November 2011 Shell signed a $17.2 billion associated-gas gathering and

monetization joint venture called Basrah Gas Company (B.G.C., 51 percent Iraq's

South Gas Company 44 percent Shell, and 5 percent Japan's Mitsubishi) for three

major Iraqi oil fields (Rumaila, Zubair, and West Qurna, all literally close to the

Iraqi-Kuwaiti north border)[xx].

This 25-year deal will help Iraq to capture more than 700 million

cubic feet per day of gas. Shell

officials previously affirmed that with the utilization of a floating L.N.G.

terminal, the first shipment could arrive within 18 months of signing a

contract. This Iraqi gas—whose 70 percent is currently flared—is supposed

to support electricity generation in Iraq, but, given that some power plants

have still to be constructed, in the first years of the construction project

there will be a gas surplus available for export. Probably working with L.N.G.

could give some flexibility, but it should be considered that being the distance

less than 3,000 miles, the economic viability of the project is yet to be found

and it seems better to fix the old pipeline that was halted in 1990.

Still in Iraq, in October 2010, the Kuwait Energy

Company, an independent oil and gas company from Kuwait, was awarded a 20-year

contract for developing Siba and Mansuriya gas fields. The Siba field is located in Basra Governorate

and the Mansuriya field in Diyala Governorate. The Kuwait Energy Company jointly bid with

the Turkish Petroleum Corporation (T.P.A.O.), the national oil company of Turkey,

for both gas fields. The Kuwait Energy Company will be the operator at Siba,

participating with a 60 percent share, while T.P.A.O. will have the

remaining 40 percent. T.P.A.O. will be the operator of Mansuriya, participating

with a 50 percent share. There, the Kuwait Energy Company and Korea Gas

Corporation (Kogas) will have respectively a 30 percent share and 20 percent

share. In particular, the Siba field— which is the smallest with 34 BCM—could provide

Kuwait with Iraqi gas, but political relations are not yet well defined in order

to materialize the project. Plus, before 2016 it's unlikely to have any gas to

export.

With no doubt, dependence on gas imports is deemed a

source of energy insecurity especially in a very unstable region as the Persian

Gulf, but alternative solutions do not abound, especially in consideration of the

current political tensions in the Gulf area. And the same time, Kuwait is not immune

to this climate of instability (since 2006 the prime minister has resigned

seven times because of political turmoil).

2.4. Kufpec's Investment in North-Western Australia's

L.N.G. Projects

The Australian projects

represent for Kufpec, Kuwait's company for foreign petroleum exploration, part

of a plan aimed at increasing Kuwait's access to global gas supplies and

improving its oil and gas technical expertise. Other Kufpec's projects are also

developed in Pakistan, Indonesia, and Malaysia with similar targets. However, Australia offers two interesting advantages: very stable fiscal terms and high

geological potential.

In particular, two operations

stand out in Australia: the partnership with the American energy company, Apache

in the Carnarvon Basin, and the participation as equity holder in the Wheatstone

Project.

Kufpec joined forces with Apache

to explore and develop gas prospects including the Julimar and Brunello fields in

the Carnarvon Basin, off the north-west coast of Australia. The partnership has

licenses for areas located close to the Wheatstone gas field (Chevron has 100

percent interest there) and to the Gorgon and Pluto gas fields where two other

large L.N.G. projects are under development.

Then, in October 2009, Kufpec-Apache

signed an agreement with Chevron to supply gas to Wheatstone L.N.G. plant (located

at Ashburton North, Western Australia and operated by the American company, Chevron)

in return for equity stakes in the project. Presently, Kufpec owns 7 percent of

the project[xxi].

In specific, Kufpec-Apache will be supplying gas from their Julimar-Brunello joint venture block (where Kufpec has a 35 percent interest, while the remaining 65 percent belongs

to Apache) which is operated by Apache. On completion, the Ashburton North

plant will receive gas from the Wheatstone, Lago, Brunello and Julimar gas fields, and it will have a production capacity

of 15 million tons.[xxii]

2.5. L.N.G.

Isn't a Temporary Measure and Needs Better Management

No

country would like to be dependent on importing energy resources. And Kuwait

does not escape this unwritten rule when dealing with gas needs. Once the

construction of nuclear power plants in Kuwait was ruled out, it appeared

evident that L.N.G. imports would not be just a temporary measure, but that they

would be part and parcel of Kuwait's energy mix. At the beginning, L.N.G.

importation was considered just a move for getting additional energy

especially during summer months with simple L.N.G. cargo purchases from

international energy companies (for instance Shell). Now, such purchases do not

cover the current needs, and L.N.G. trade should be organized in a much larger scale and permanent basis. At least, Kuwait could try—as it is

partially doing—to increase its domestic production of both associated and

non-associated gas with the final target of limiting L.N.G. imports.

In

order to receive L.N.G. supplies on a permanent basis, some steps need to be

implemented soon both with reference to the infrastructural side and to the

contractual side. On the one end, for a cash-rich country like Kuwait, it's not

difficult to built new gas infrastructures. In this regard, there are already

some plans to build a permanent L.N.G. regasification facility to take the

place of the current L.N.G. infrastructure at the Mina Al-Ahmadi gas port. On the other end, defining a strategy for long-term

L.N.G. supplies from a bilateral and reliable supplier could be not so easy. In

the last two years, Shell and Vitol have provided for the required gas needs,

but at the end of 2013 summer season those contracts will expire. Kuwaiti

officials point out that they will buy gas on the open market, but it seems

quite a bet not to sign any long-term contract with an L.N.G. producing

country.

Although

up to now there has been no room for an accord with either QG or RasGas, a real candidate for an L.N.G. contract relation is

Qatar, which has the world's third proven natural gas reserves, is capable of

producing 77 million tons of L.N.G. per year, and is by far the largest L.N.G.

exporter in the world. For Kuwait, which is geographically close to Qatar (Kuwait

City is just 357 miles from Doha) renouncing to Qatari gas would mean

relinquishing a good opportunity, although the proximity between Kuwait and

Qatar reduces the economic viability of utilizing L.N.G.

Perhaps

Kuwait and Qatar will have to reassess their pricing structures: The latter has

to reconsider the selling price structure and the former the purchasing price

structure. Taking into account Qatar's L.N.G. glut (it will have to sell L.N.G.

more to Asia than to America as previously planned), Qatar may well agree to

sell gas at lower price. But Kuwait needs to raise the price it's willing to pay

for L.N.G. shipments[xxiii].

In effect, considering the global oversupply of L.N.G., both Qatar and Oman could

start renegotiating their L.N.G. export agreements (in general, including

off-take or take-or-pay conditions). In this way, these countries would have

more natural gas to trade at the intraregional level (for instance between

G.C.C. countries)[xxiv] that

is a market which in the next years will be booming.

CONCLUSION

Importing natural gas to Kuwait—an oil-rich country which possesses also 1 percent of the world's natural gas

proved reserves—seems a paradox, but it's real and it's happening right now.

Also some other G.C.C. countries, all with consistent natural gas resources,

already started importing gas or are developing plans for gas importation.

After Kuwait's oil and gas complete

nationalization (gas in 1971 and oil in 1975), no I.O.C. was allowed to

operate in Kuwait for at least 15 years. The oil and gas sector became closed

to foreign actors. The only exception was Chevron in the P.N.Z. Then, after the

end of the First Gulf War, as a consequence of the war damages to crude oil

fields and of the understanding that the era of easy oil was close to an end,

Kuwaiti authorities permitted I.O.C.s to sign T.S.A.s (now E.T.S.A.s) in

relation to Kuwait's oil and gas sector. These contracts proved not very

successful for both sides to the deal. In fact, I.O.C.s are not able to make a

profit, and Kuwait is not getting the modernization and upgrade of its oil and

gas sector.

The current contractual

framework seems unable to produce the corrective measures for solving the

problem of gas shortages. Kuwait would like to increase its production of

non-associated gas fields, but this task is not easy, because K.P.C. does not have

the skills for developing geological and technically complex gas fields both

onshore and offshore. All these said, gas shortages are today's problem and the

development of non-associated gas fields—assuming that I.O.C.s could better

assist K.P.C. in the development operations—will require some years before

giving a reliable and consistent output (at the Dorra offshore gas field there

could be also political problems with Iran).

Apart from the non-deferrable reform

of Kuwait's contractual oil and gas framework, in order to be successful in avoiding

gas shortages, Kuwait's strategy should be based on the following 5 pillars:

- Developing Kuwait's

non-associated gas from the gas fields located in the northern part of the

country

- Developing the Dorra offshore non-associated

gas field located in the P.N.Z.

- Purchasing L.N.G. on a

permanent basis in the spot market as well as with medium-term agreements

- Importing natural gas via pipelines

from neighboring countries

- Directly investing into L.N.G.

operations abroad (Kufpec)

All

these five pillars may give positive outcomes, but in the near- to medium-term

the only available and fast solution (for instance with floating terminals) to cover Kuwait's natural gas demand in excess of natural gas domestic

production is through L.N.G. spot and medium- to long-term contracts. It's true

that when L.N.G. shipments are routed for less than 3,000 miles—and it's

quite probable to have L.N.G. shipped to Kuwait from countries located within

the Persian Gulf (615 miles long at its longest point and 180 miles wide at its

widest point—it's difficult for the buyer (in this case Kuwait) to have also

a sort of economic viability. The problem is that the regional political

instability also makes very difficult to realize pipelines. However, with no doubt,

pipelines would be much more economically convenient than importing L.N.G. for

short distances like within the Persian Gulf.

If

Kuwait is going to import L.N.G. on a more-than-temporary basis it would be

advisable to sign medium- to long-term contracts with some reliable suppliers more than to sign just spot contracts. A candidate supplier could be Qatar, although

the proximity between the two countries eats out any economic convenience for

Kuwait. The failed negotiations between Kuwait, on the one side, and RasGas, on

the other side, well testify to the difficulties of reaching an agreement under narrow

economic margins. In this regard, it would be interesting to obtain full disclosure

about the price paid by Kuwait in relation to the two medium-term L.N.G.

contracts with Vitol and Shell. For the moment, the only thing that is sure is

that at least for the next three years alternatives to L.N.G. imports do not

abound.

[ii] OPEC comprises 12

members: Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United

Arab Emirates

and Venezuela.

[iii] Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman,

Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are the six G.C.C. members.

Jordan and Morocco have been invited to join the G.C.C.

[v] CHISHOLM, A., The First Kuwait Oil Concessions: A Record

of the Negotiations. Cass, London, 1975.

[vi] BELTRAME, S., Storia del Kuwait, CEDAM, Padua, 1999.

[viii] AL-SABAH FADEL, Y.S., The Oil Economy of Kuwait, Keagan Paul

International Ltd., London, 1980.

[ix] CLO', A., Oil Economics and Policy, Kluwer, 2000,

p. 105.

[x] JOHNS R., FIELD, M., Oil in the Middle East and North Africa

in The Middle East and North Africa, 1987 (33d ed.) , London.

[xi] Here it's considered

not the original K.O.C. created by Anglo Persian Oil Company (then British

Petroleum) and Gulf Oil in 1933, but the mixed private/public company established in

1974 whose 60 percent belonged to BP/Gulf, while the remaining 40 percent to

the state of Kuwait.

[xiii] Prime Minister Sheikh

Nasser has so far resigned seven times since he was appointed prime minister in

February 2006.

[xiv] Oil and gas reserves

are the principal assets of an oil and gas company, and booking is the

process by which reserves are added to the company's balance sheet. This is

done according to a set of rules developed by the Society of Petroleum Engineers (S.P.E.).

"The

essence of upstream investment is the ability to book new reserves. Booking

reserves means that the corporation has the contractual right to produce the