The

analysis “Kuwait’s Petroleum Sector: What Is the Right Strategy?” has been written

for the 5th Kuwait Oil and Gas Summit, which is organized by The C.W.C. Group, an energy and infrastructure conference, exhibition and training

company. The 5th Kuwait Oil and Gas Summit will take place in Kuwait

City, on April 16-17, 2018.

April 12, 2018

London, United Kingdom

With

101.5 billion barrels of oil (BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2017), Kuwait

owns the world’s seventh largest proven oil reserves, or 5.9% of the world’s proven

oil reserves. The country’s economy is dominated by the oil sector. In fact, more

than 50% of the G.D.P, 92% of export revenues (from oil and oil products and

fertilizers), and 90% of the government income come all from the oil sector

(C.I.A. World Factbook, 2018). With reference to natural gas, Kuwait, with 1.8

trillion cubic meters (Tcm) of natural gas (BP Statistical Review of World

Energy 2017), on par with Norway and Egypt, owns the world’s 16th

largest proven natural gas reserves, or 1.0% of the world’s proven natural gas

reserves.

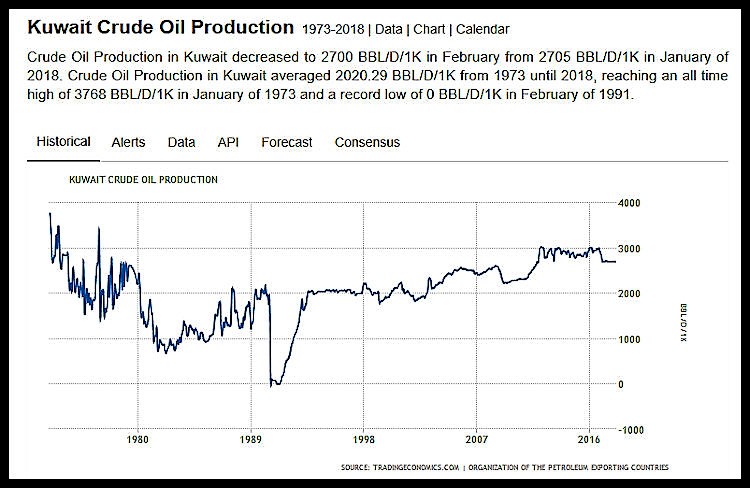

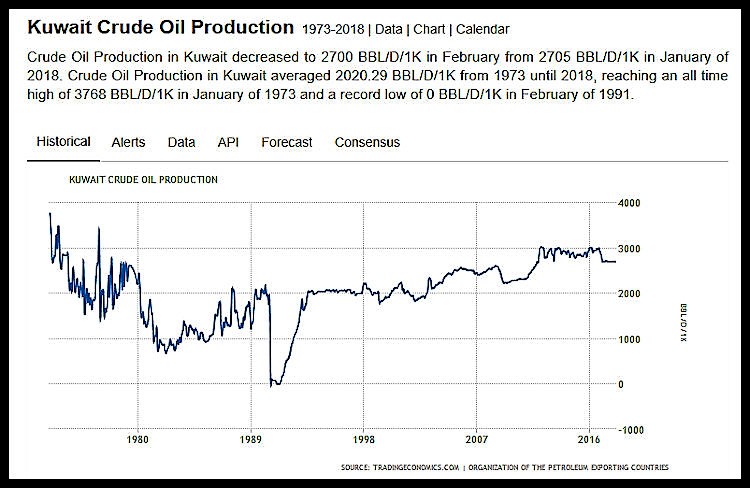

Kuwait

has a production capacity of about 3.1 million barrels per day (MMb/d) and an

effective production of about 2.7 MMb/d. Kuwait’s production of about 250,000

b/d at the Wafra (onshore) and Khafji (offshore) fields in the Partitioned

Neutral Zone, which is the border region between Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, has

been shut down since 2015. At the current rate of production, Kuwait’s oil should

last for almost 88 years, while gas reserves for more than 100 years. Kuwait,

as well as the other Persian Gulf producers, has a couple of important

advantages: very low production costs and a geographic position at the

crossroads of three continents (Europe, Africa, and Asia), which permits Kuwait

to easily export oil and oil products to more than one market.

Kuwait

has production costs among the lowest in the world. In fact, it has had until now

production costs of about $8.50 per barrel on average (in specific, $3.70 for

capital expenditures and $4.80 for operating expenditures). Probably, these

production costs will relatively rise in the future because production will

derive from more complex fields. However, because oil is a commodity (despite

different A.P.I. degrees and sulfur content), low production costs are one of

the most important commercial advantages for an oil producer.

At

the same time, thanks to its geographic position, Kuwait may easily export its

oil to the Asia-Pacific region, which receives about 80% of its oil exports (Kuwait’s

overall exports are estimated at about 2.0 MMb/d). Crude oil is primarily sold

on term contracts, and its crude oil exports have been until recently a single

blend of all the Kuwaiti types of crudes, which is called ‘Kuwait.’ This blend

has 30.5 A.P.I. degrees and 2.6% of sulfur content (it’s defined a sour crude).

Presently, with the help of some Asian refiners, Kuwait is testing in Asia whether there

might be some interest in a new Kuwaiti blend called ‘Super Light,’ which has an

A.P.I. gravity of 48 degrees and 0.4% of sulfur content. In addition, in

August 2018, Kuwait wants to launch the blend ‘Kuwait Heavy,’ which has an

A.P.I. gravity of 16 degrees and 4.9% of sulfur content.

So,

Kuwait represents a reliable and secure oil producer, which has been in the oil

business since 1938 when oil was discovered four years after the signature of

the concession in favor of a joint venture between Anglo-Persian Oil Company

(today’s British Petroleum) and Gulf Oil (today part of the U.S. company Chevron).

And, for all these decades, apart for a short hiatus linked to the invasion of

Kuwait by Iraq’s army, Kuwait has been one of the world’s most important and

reliable producers.

However,

because of the evolving energy scenarios linked primarily to geopolitical

considerations, disruptive technologies, and climate change goals, it has

become more difficult for a petroleum-producing country to understand the

future opportunities and challenges concerning the petroleum sector. In

practice, the petroleum industry is in transformation, and all the petroleum-producing

countries (but, it would be more correct to add all the petroleum-importing

countries as well) must learn how to mitigate the present uncertainties. And,

as a producer, Kuwait is not exempt from this difficult challenge.

In

addition, these uncertainties regarding the development of the world’s

petroleum industry are added in Kuwait to an economy that is completely

dependent on the sales of oil and oil products. In fact, despite some attempts,

Kuwait has not succeeded in diversifying its economy and in supporting the

development of the private sector. The public sector employs about 74% of the

citizens. Be it clear that these economic features are quite widespread among

all the Persian Gulf producers (neighboring Iraq is experiencing the same economic

problems in addition to high costs linked to the reconstruction after the ISIS

insurgence).

The

level of a country’s petroleum dependence can be measured according to several

different methodologies. In any case, three good indicators may be: petroleum

activities representing a sizable share of G.D.P., petroleum rents representing

a sizable share of G.D.P., and petroleum exports representing a sizable share

of the merchandising exports. In brief, Kuwait has high values in relation to

all these three indicators.

|

What Did Kuwait Export

in 2016? — Source: The Atlas of Complexity, Harvard University

|

The

government had passed its first long-term economic development plan in 2010.

The idea was to spend up $104 billion over just four years with the specific

goal of diversifying the economy, bringing investments in Kuwait, and

increasing the private-sector share of the economy. Many of these projects

never materialized because of the uncertain political situation and the delays

in awarding the contracts.

In

Kuwait, diversification is not happening primarily for two reasons. First, because

it’s never an easy task to diversify the economy of a commodity-producing

country. And this is true no matter in what part of the world we are. Also, for

a country like Norway, which is normally considered the model of a successful petroleum-producing

country, diversifying the economy (although not completely) has not been an

easy task, and several specific (of the Norwegian state) factors helped Norway

reach this goal. In fact, for a commodity producer, there is always, behind the

corner, the risk of facing two dangerous phenomena, i.e., the Resource Curse

and the Dutch Disease.

Second,

diversification is not happening in Kuwait because of the difficult

relationships between the National Assembly, on the one side, and the executive

branch, on the other side. Historically, in Kuwait, the relationships between

these two institutional bodies have never been simple, and they have stymied

many economic reforms proposed over the years. A strong confrontation between the

National Assembly and government concerning the way to deal with the management

of the natural resources according to the interpretation of the text of the

Constitution had already materialized in the 1960s.

However, many petroleum-producing countries find

themselves in dire financial straits after an oil’s price fall, as it occurred

in 2014. So, if a country’s economy is based on just a single pillar, when this

pillar is not any longer stable, there are bad economic consequences for the country.

In practice, a single-pillar economy has lower resilience against shocks

affecting its single pillar than the resilience of an economy based on several

different pillars. And this is what exactly occurred to Kuwait. The adage ‘never

put all the eggs in a single basket’ is true for private investors as it is for

countries.

In fact, in 2015, for the first time in 15 years,

Kuwait realized a budget deficit. The following year, the deficit increased to

16.5% of the G.D.P. Then, in 2017, the deficit decreased to 7.2%. At the same

time, the government issued $8 billion’s worth of international bonds—there is

a trend in this direction in the Gulf Cooperation Council (G.C.C.) region. Kuwait’s

Fund for Future Generations, the sovereign wealth fund, in which each year Kuwait

saves at least 10% of government revenues, helped cushion Kuwait against the

impact of the reduction in the oil prices. Without capital expenditures and

social allowances, the latter make up two thirds of the private sector

salaries, the economy would have slowed more consistently.

Considering the above points, it appears clear

that Kuwait’s overall economic development must pass through the

diversification of the economy and a boost in private-sector hiring. However,

as economic literature has well explained, this is easier said than done,

especially in a country subject to harsh weather conditions as Kuwait is.

Probably, the best route would be the development of industrial clusters linked

to Kuwait’s characteristics and not a top-down industrial policy established by

the government.

As the theory of cluster development explains,

clusters pursue competitive advantage and specialization, and they do not

attempt to replicate what is happening in other locations. With clusters,

[g]overnments – both national and local – have new

roles to play. They must ensure the supply of high-quality inputs such as

educated citizens and physical infrastructure. They must set the rules of competition

– by protecting intellectual property and enforcing antitrust laws, for example

– so that productivity and innovation will govern success in the economy.

Finally, governments should promote cluster formation and upgrading and the buildup

of public or quasi-public goods that have a significant impact on many linked

businesses. This sort of role for government is a far cry from industrial

policy. (Porter, 1998)

So,

branching out to other industrial sectors according to a cluster logic may be

the correct way. Kuwait might be the location for clusters related to technologies

linked to living in hot environments. For instance, technologies linked to

water desalinization, solar energy, and agriculture in arid lands.

Instead,

with reference to the petroleum sector, the correct

strategy, despite all the present uncertainties, must be continuity with the

past. Here the logic must be to understand what Kuwait can and cannot do now

and in the next years. In fact, notwithstanding all the ongoing discussions,

it’s impossible for Kuwait not to rely on the revenues deriving from the sale

of oil, which has been for the last decades and will continue to be, at least in

the near future, the country’s most important asset. As of today, without oil

revenues, numbers tell us that Kuwait’s economy would come to a grinding halt. Plus,

it’s important to understand that diversifying the economy would take years

before making a dent on the current structure of Kuwait’s economy, which is

dependent on the export of oil and oil products.

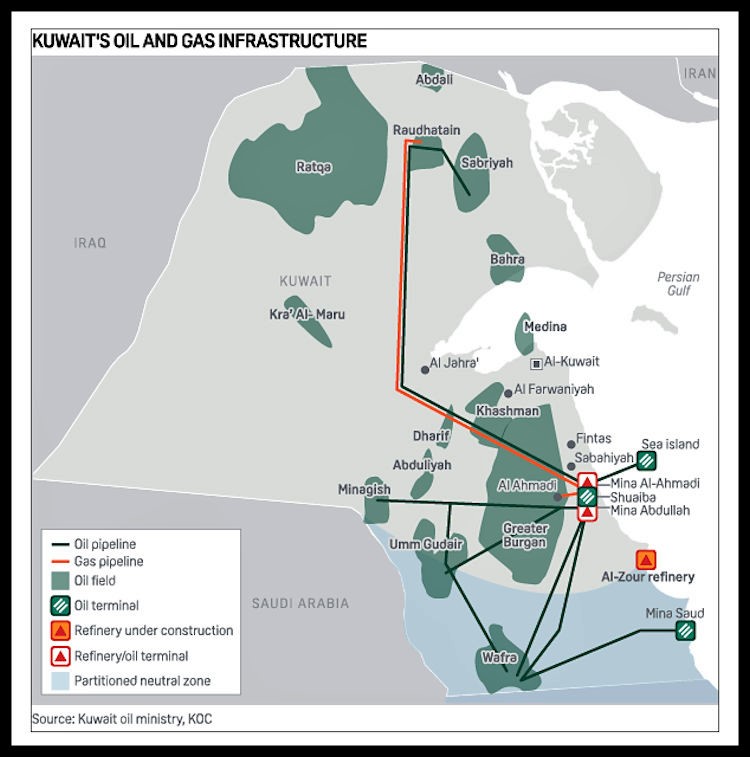

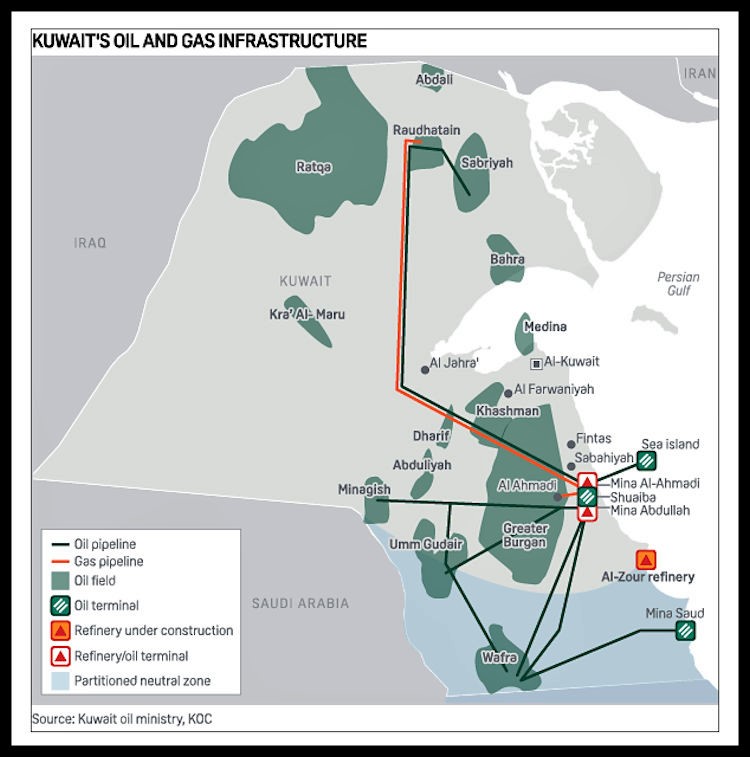

In 1997, Kuwait formulated ‘Project Kuwait,’ at

that time a $7 billion 25-year plan having the goal of increasing the country’s

oil production capacity (and compensate for the decline at the supergiant Burgan

field) with the help of international oil companies (I.O.C.s). In specific,

Kuwait wanted to initially increase output at five northern oil fields—Abdali,

Bahra, Ratqa, Raudhatain, and Sabriya—from a production rate of about 650,000

b/d to 900,000 b/d within the following three years. Then in mid-2000s, the basic

idea of the project became to increase the country’s oil production capacity to

4.0 MMb/d by 2020.

This whole project has not materialized until now despite

the authorities have always reaffirmed until recently that this is still an

achievable target. The main reason for the delay is the political opposition to the

I.O.C.s and to the contractual structure offered to them. Many of the new

projects have faced relevant delays because of the National Assembly’s

opposition to the envisaged new contractual structure. For more information

about Kuwait’s petroleum contracts, please see: BACCI, A., Kuwait's Oil and Gas Contractual Framework

and the Development of a Modern Natural Gas Industry (Dec. 2011).

In brief, in order to bring in Kuwait the I.O.C.s, at

the end of the 2000s, Kuwait started to offer Enhanced Technical Service Agreements

(E.T.S.A.s), which allow the foreign companies to provide technical expertise

(needed especially for the more challenging fields) and management expertise for

a fee. Kuwait’s politicians have always been quite skeptical about the

transparency of the E.T.S.A.s and whether what Kuwait receives in exchange for

these services is fair. In any case, in the past ten years, Kuwait has signed

some E.T.S.A.s with Shell, BP, and Total, although the development of the

contracts has been marred by several missed deadlines.

Kuwait

won’t probably achieve the target of 4 MMb/d by 2020, but Kuwait Petroleum

Corporation (K.P.C.) has recently affirmed that it intends to invest more than

$500 billion to push its petroleum production to 4.75 MMb/d by 2040. Whether

the 4.75 MMb/d target includes Kuwait's production from the neutral zone is not

clear. In any case, this increase will derive mostly from northern Kuwait,

which is currently producing 1 MMb/d. In

specific, the company should spend $114 billion in capital expenditures over

the next five years and additional $394 billion after the initial five years up

to 2040.

In

practice, although the petroleum market has changed consistently over the past

10 years, Kuwait proposes again an oil-production expansion plan. And, despite

that Kuwait is subject to OPEC quotas and that OPEC and non-OPEC members are

currently restraining their crude oil production to support oil prices, there is a logic

behind this choice. And Kuwait is not the only country carrying out this type

of plan. In fact, throughout the Persian Gulf oil-producing countries, there is

a medium-term trend toward expanding crude oil production (see for instance the

expansion plans relating to Iraq and Iran as well).

With

reference to oil, all these countries share the same advantages that Kuwait

has, i.e., low crude-oil production costs and an interesting geographic position

capable of serving more than one market (the favored one is the Asian market

now). And because oil is a commodity (let’s put aside the differences relating

to A.P.I. degrees and sulfur content) and considering the two above-mentioned

advantages, if oil markets were not affected by distortive political and

economic barriers, it would be evident that the most obvious oil producers in

the world should always be the Persian Gulf producers and Russia as well. Think

of David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage. So, summing up, this

medium-term trend tells us that these countries, including Kuwait, are betting

on cashing in on these two mentioned advantages, if not today, on a medium-term

horizon.

What

Kuwait is slowly trying to achieve is probably the correct strategy under the

present uncertain circumstances. In any case, selling oil and oil products will

require a more detailed attention to the whole petroleum chain, from upstream

to downstream. In fact, competition among producers is increasing both at the

regional and at the international level with the specific goal of capturing

opportunities in the market. For sure, Kuwait is well positioned to take

advantage of the growing oil demand occurring in Asia, but this is true for all

the other Persian Gulf producers as well, and it seems that in the future also

oil producers from other geographic areas might try to sell oil in Asia. For

Kuwait, enhancing customer relationships will be crucial to maintain prearranged

fixed sales agreements, which guarantee a certain cash flow. Because oil is a

commodity, differentiation strategies are not easy to implement. One route

might be to have an enlarged role in relation to oil trading.

At the

same time, Kuwait must necessarily continue to increase its production of non-associated natural gas; its associated natural gas production makes up 80% of the total natural gas

production. According to BP Statistical Review of World

Energy 2017, Kuwait in 2016 produced 17.1 billion cubic meters (Bcm) of natural

gas, while it consumed 21.9 Bcm. The goal is to

increase non-associated gas production to 2.5 billion cubic feet a day (Bcf/d)

in 2040 from the level of 0.5 Bcf/d in mid-2018. Kuwait needs large supplies of natural gas to generate

electricity and to carry out water desalination, petrochemical production, and

enhanced oil recovery to boost oil production. In

specific, the electricity sector often fails to generate enough electricity to

meet peak demand.

Moreover,

because Kuwait for a good share produces electricity by burning oil and other

liquids, which in this way are not exported, Kuwait is currently losing

revenues from the missed sales of this oil and other liquids. More domestic

natural gas production from non-associated gas fields might free some

quantities of oil for export with consequently the result of increasing the

revenues for Kuwait. The need to increase natural gas availability is quite

urgent because domestic energy

demand is going to double between 2017 and 2030.

Kuwait has been relying on L.N.G. imports since

2009 when natural gas consumption overpassed domestic production, and this

trend seems not to abase. In December 2017, K.P.C. signed a 15-year L.N.G. gas

import deal with Shell (the deal will start in 2020) to help Kuwait to continue

to close the gap between its gas demand and its gas production. At the end of

the 2000s, the country started to develop, although slowly, its non-associated

gas reserves, primarily from the Jurassic non-associated gas field (technically

quite challenging) in norther Kuwait. This field was discovered in 2006 and has

35 Tcf of estimated reserves. In 2017, the government approved the second

phase of the North Kuwait Jurassic Gas project, and, finally, this year three early

production facilities, Sabriya and Umm Niqa fields, East Raudhatain field, and

West Raudhatain field are coming online. Together, these facilities will produce

200,000 b/d of light crude and 500 MMcf/d of natural gas.