July 28, 2015

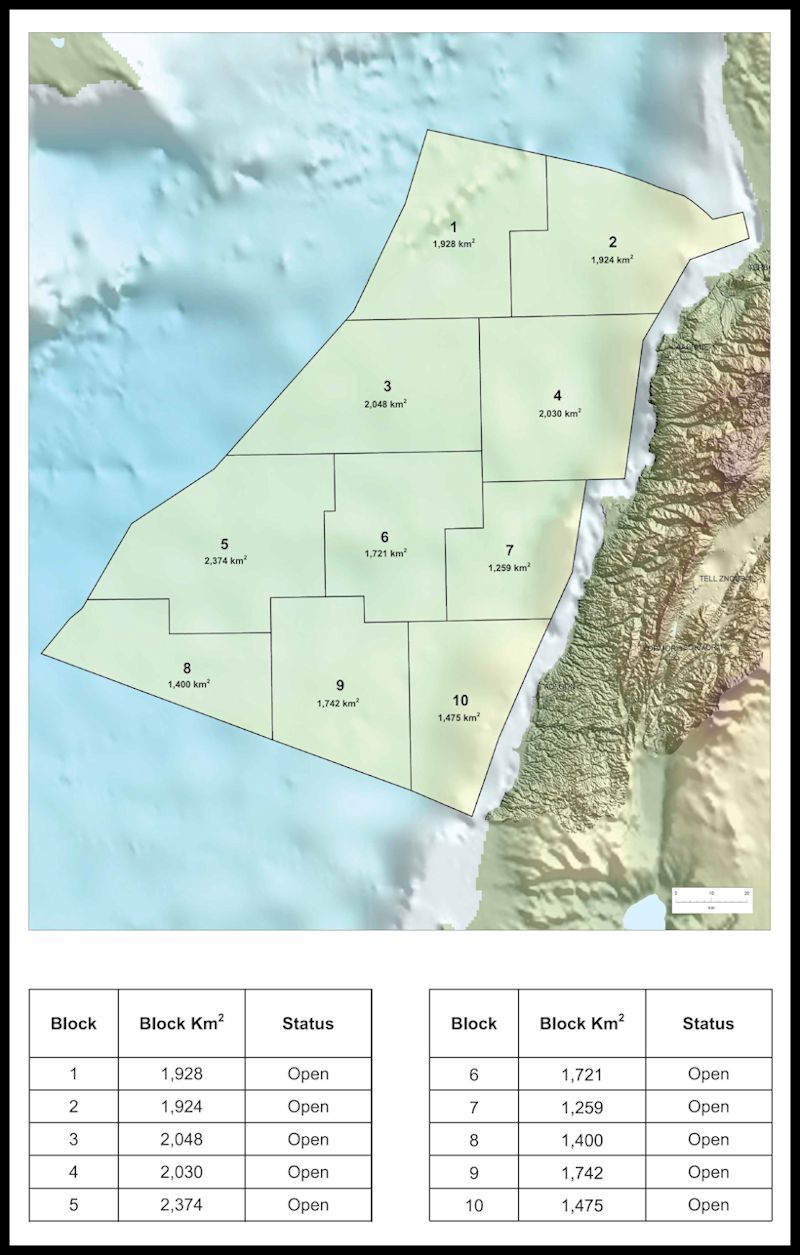

ABSTRACT — After some years of careful

planning, in 2013 Lebanon was on the verge of launching an auction for the

first licensing round in relation to its offshore natural gas potential. Two

decrees, one related to the division of the Lebanese economic exclusive zone

(E.E.Z.) into 10 blocks, and one related to the exploration and production

agreement (E.P.A.), i.e., the petroleum contract that Lebanon wants to sign

with the international energy companies interested in Lebanon's hydrocarbons,

were the prerequisite for the auction. Unfortunately, the government has never

approved these two decrees, and the auction has been postponed since then. The

aim of this paper is to analyze the importance of these two degrees with a

particular attention given to the E.P.A. degree with its related fiscal

issues.

BEIRUT, Lebanon — In July 2015 the

question of the demarcation of the maritime border with Israel has one more

time been brought to the limelight of Lebanon's political debate. At the beginning of July, during a visit to Lebanon, Amos Hochstein, the U.S. special envoy for international energy affairs at the State Department, reaffirmed that

if Lebanon intends to start developing its offshore oil and gas reserves it has

to deal with the complex issue of the maritime demarcation with Israel. Acouple of weeks later, Energy and Water Minister Arthur Nazarian expressed its hope that the U.S. may consider a Lebanese request to have the U.N. help demarcate the maritime frontier between Lebanon and Israel where there could be

natural gas reserves buried beneath the seabed. In specific, Israel and Lebanon

quarrel as for a maritime area of 874 square kilometers. In July 2010, Israel

defined and adopted a delineation of its exclusive economic zone (E.E.Z.) that

conflicts and overlaps with Lebanon's E.E.Z.

|

| Source: "Lebanon’s Maritime Boundaries: Between Economic Opportunities and Military Confrontation" by D. MEIER (June 2013) |

In recent decades the technological

possibility of exploring offshore oil and gas has transformed basic maritime

issues into contentious issues. Before this new offshore exploration spree,

many maritime borders were not delimitated; there was no real economic value

linked to a detailed delimitation. Previously, the only real contentious issues were fishing rights and the passage of military vessels — surely important

issues but with a more modest economic value than hydrocarbons and minerals.

Suddenly, things change when there is the possibility that in the areas

straddling between two or more countries there are, buried in the seabed,

commercially relevant deposits of hydrocarbons or minerals. One of the most known examples of these maritime disputes is related to the South China Sea where seven states — China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan, Vietnam

and Brunei — are claiming the ownership of energy supplies buried beneath the

seabed. These kinds of disputes are present in all of the world seas, and the

eastern Mediterranean Sea is not an exception. In addition to this, in the

Levant Basis, some of these maritime disputes are reinforced by the strained

relations between the involved countries. In the eastern Mediterranean, the two

of the most contentious issues are:

The state of war between Israel and

Lebanon, at least technically speaking. The Israeli-Lebanese relations have

never existed under normal economic or diplomatic conditions, although Lebanon

was the first Arab League nation to show a desire for an armistice treaty with

Israel in 1949. After the 2006 Lebanon War (in Lebanon a.k.a. July War), which

ended in August 2006, Israel and Lebanon have not been fighting anymore — apart

from some border incidents once in a while — but still a state of war is the

technical current condition between the two countries.

The tense relations between the

Republic of Cyprus (Cyprus proper) and Turkey in relation to the division of

the island of Cyprus between the Republic of Cyprus, which is recognized at the

international level, and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which is an

entity recognized only by Turkey. With reference to Cyprus' offshore energy activities there is an overlapping between some of the Republic of Cyprus' oil and gas research blocks (blocks number 1, 4, 5, and 7) and Turkish continental shelf claims.

The maritime border dispute between

Israel and Lebanon is not easy to solve. While Lebanon ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos) in January 1995, Israel has

never signed nor ratified Unclos. In practice, this means that the only

possible road in order to solve this matter is for Lebanon third party

mediation possibly through the United Nations (U.N.). In fact, in no way may

Lebanon force Israel to court (for instance, the International Court of Justice

(I.C.J.), the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea or the Permanent

Court of Arbitration) because there is simply no jurisdiction applicable to

Israel. It's clear that this territorial dispute will impede Lebanon from

developing its hydrocarbons buried beneath the seabed under the above mentioned

874 square kilometers. And, if, on the one hand, it's true that

"[p]roclaiming an E.E.Z. is now part of customary law, as made by international lawyers, and therefore opposable even to States not partied to Unclos like" (Meier, 2013), it's also true that for two countries in a

state of war it's difficult to reach an equitable agreement on the basis of

international law (for instance, the equidistance line from the baselines between the countries).

Lebanon's E.E.Z. is an expanse of 22,730 square kilometers of water bordering Syrian, Israeli, and Cypriot

waters. This indicates that the disputed area is equal to only 3.84 percent of

Lebanon's E.E.Z. In other words, is it reasonable for Lebanon to wait for a

solution in relation to the maritime border before starting to develop its

offshore hydrocarbons? Economically speaking, the answer is no. It seems that at least two blocks (block 8 and block 9) out of ten have part of their

territory disputed with Israel. So, the Lebanese government could implement a

bidding process for part of the blocks that are completely within

Lebanon's E.E.Z. As for the remaining blocks, Lebanon could imagine some

solutions in order to permit to lease them without creating an escalation with

Israel. For instance, it could be advisable to refrain from exploring in the disputed

territory (creating a sort of buffer zone). If following this road the reduced blocks were less attracting to the potential bidders, the

government should look for some counterbalancing solutions (for instance,

improved fiscal terms for the I.O.C.s bidding in relations to the reduced

blocks, or redrawing the borders among all the ten blocks). Bear in mind that

the petroleum literature well explains that there is no ideal block size; in

general, a block size is defined according to:

A) Geology

B) Location

C) Competition

D) License duration and

E) Relinquishment rules

With reference to block delineation, a

final but important consideration is that a government has never to award all

of its offshore and/or onshore territory for exploration and exploitation

simultaneously; this rule is particularly true when a government is awarding

unexplored acreage with many unknown factors involved. In fact, especially when

dealing with frontier territory, designing immediately an almost perfect

contractual framework with its related fiscal terms is practically an

impossible task, so it's much safer for a government to award its territory in

a gradual manner utilizing for every new award the information obtained through

the previous exploration and production agreements (E.P.A.s).

Currently, Lebanon's offshore gas

dossier is not progressing at all (For more information see: BACCI,. A., Lebanon's Offshore Natural Gas: A Complicated Story, May 2015). In order to advance with the gas business,

it is necessary that the government approves two decrees: the first one

concerning the demarcation of the 10 maritime blocks (the division of the

exclusive economic zone) and the second one concerning the details of the

production sharing agreements (P.S.C.s) to sign with the I.O.Cs. Without these

two decrees it is not possible to have the auction for the assignment of the

blocks — an auction which has been postponed several times since October 2013.

In July 2015, all this attention and

interest given to the necessity of finding a solution to the maritime

border before drafting the decree related to the Lebanese E.E.Z. do not seem

very economically rational, if Lebanon is fully committed to exploring and

later exploiting its offshore gas potential. In 2010, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that the Levant Basin could have 122 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of undiscovered natural gas resources and 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil. Thanks to recent discovery of natural gas offshore, both Cyprus (Aphrodite

7 TCF) and Israel (Tamar field 10 TCF and Leviathan field 18 TCF) have the

potential to become natural gas exporters. Indeed, Lebanon, which according to

Spectrum, a Norwegian company working in the seismic services market, could

have up to 25.4 TCF of recoverable offshore gas reserves, is already quite late

if it intends to develop its offshore potential — if Lebanon started developing

its offshore sector now, it would not be able to export gas before 2025.

If the two above-mentioned decrees are

not passed because there are some doubts about the economic side of the

development of an offshore natural gas sector in Lebanon, this kind of

substantiated opposition is perfectly acceptable and could be logic (of course,

it needs an explanation). But, if the two decrees do not advance for political

reasons, this does not serve the long-term interests of Lebanon. And the

reemergence of the problem related to the maritime border with Israel appears as

a new (ad hoc formulated) stumbling block capable of delaying the advancement

of Lebanon's offshore gas dossier while it could be possible to draft the

E.E.Z. decree with the precaution of not exploring within the disputed area.

Now, it is not anymore confirmed that all of the 46 companies (12 as operators)

that prequalified for the auction will continue to show interest for Lebanon's

natural gas (For more information see: BACCI, A., Forty-Six I.O.C.s Will Bid for Lebanon's Offshore Hydrocarbon Exploration, April 2013).

Until the moment when it was supposed

to pass the two mentioned decrees, the Lebanese government had acted in a

correct manner. Uncertainty about the geological potential embodies the lion's

share of the risk associated with a petroleum project. And starting a

'negotiation' with I.O.C.s — by the way of an open-door system (negotiations

between the government and interested investors through solicited or

unsolicited expression of interest) or through licensing rounds (administrative

procedures or auctions) — with scarce geological information means starting off

on the wrong foot, highly increasing the probability of being forced to

renegotiate the signed contracts quite soon. So, in light of these concerns,

ahead of licensing exploration and production rights, the government had

contacted Petroleum GeoServices (P.G.S.) and Spectrum, two companies active in

the seismic service market. These companies extensively mapped offshore of

Lebanon with 2-D and 3-D seismic surveys (around 70 percent), and, through the

acquisition of geophysical data, which can be sold to the interested I.O.C.s,

they lowered the geological risk and increased the interest (and consequently

the competition) among the potential investors (recently the government has

replicated the same scheme onshore of Lebanon with a U.S. company, Neos, which

has completed a geophysical airborne survey designed to map the regional

prospectivity of 6,000 square kilometers, including the onshore northern half

of the country and the transition zone along the Mediterranean coastline, by

integrating legacy well and seismic data with newly acquired airborne

geophysical datasets).

For the I.O.C.s interested in the

offshore hydrocarbons, right now the real stumbling block is the absence of a

final (adopted and signed) Exploration and Production Agreement (E.P.A.), which

is the essence of the second degree that the government has to approve yet.

Under the current available data, it's difficult for an energy company to

accurately assess whether to invest in Lebanon's offshore activities. In fact,

when in June 2013 was held a meeting between prequalified consortia and the Lebanese Petroleum Administration (L.P.A.), the involved I.O.C.s raised many complaints in several different areas: exploration phase, force majeure, time for proposing a development plan, and political risk.

At the time of this writing, Lebanon's

offshore oil and gas is mainly regulated by:

1) The Offshore Petroleum Resources Law (O.P.R.L., Law 132 of August 2010), available online on the website of the

L.P.A. This law provides a framework about how the Lebanese petroleum (oil and

gas) sector will be organized. According to the L.P.A.:

The O.P.R.L. regulates reconnaissance, exclusive petroleum rights and the exploration and production agreement between the Lebanese State and the right holders. According to this law the Lebanese State reserves the right to carry out or participate in petroleum activities. The proceeds arising out of petroleum activities shall be placed in a sovereign fund.

2) The Petroleum Activities Regulation (P.A.R.), also available online on the website of the L.P.A. The P.A.R.

presents the applications decrees for the O.P.R.L. It covers several rules

stipulated in the law. The P.A.R. provides the regulations pursuant to

conducting petroleum activities including: the legal representation of the

right holder, the management system, the general duties of the operator and the

right holder, the strategic environmental assessment, the exploration and production

rights, the petroleum production and transportation, the cessation of petroleum

activities and decommissioning, and other activities.

For I.O.C.s, together the articles of

the O.P.R.L and of the P.A.R.s surely provide some fundamental information in

order to understand how to work in Lebanon's offshore waters. But, without a

definitive E.P.A., which has to include all the biddable and non-biddable

terms, for I.O.C.s it's difficult to economically evaluate the pros and cons of

investing in the development of Lebanon's offshore natural gas. Presently, in

relation to the contractual part, in addition to these two documents, on the L.P.A. website there is only a page titled "THE EXPLORATION AND PRODUCTION AGREEMENT" where there is just some preliminary and basic information

about Lebanon's future E.P.A.

Now, let's put aside Lebanon's

prequalification criteria, which are not the main topic of this analysis (in

any case the slides below will clarify them), and let's analyze the current

available details of the future Lebanese E.P.A. with its available fiscal

terms. This does not mean that prequalification criteria do not have an impact

on the possible future fiscal terms, because as Carole Nakhle, the director of Crystol Energy, recently (July 2015) wrote:

The pre-qualification criteria that the country [Lebanon] selected clearly created a bias toward large oil companies, the rationale being that Lebanon’s oil and gas resources lie in deepwater and the larger players have the expertise and capital to exploit them.

In practice, when a country defines its

prequalification criteria, it indirectly orients the kind of E.P.A. (contract) that

the prequalified companies will accept and sign later. The idea is that, if a

country delineates prequalification criteria targeting for instance large

petroleum companies, later when it writes its E.P.A., it will have to draft a

contract with fiscal parameters in line (or at least partially in line) with

the desiderata of large petroleum companies — if the government does not

proceed so, it will have probably nullified the prequalification results, and

it will have to start the process for a second time.

Lebanon has opted to sign Production

Sharing Contracts (P.S.C.s). The slides below provide some details concerning

the structure of today's general P.S.C.s. The scheme released by the

L.P.A. shows that Lebanese P.S.C.s are well in line with the most basic form of

a classic P.S.C., which has four components as shown by the table below.

THE

FOUR MAIN COMPONENTS OF A CLASSIC P.S.C.

|

|

Royalty

|

In Lebanon: it's fixed by legislation

|

Cost Recovery

|

In Lebanon: biddable

|

Profit Petroleum

|

In Lebanon: biddable

|

Tax

|

In Lebanon: it's fixed by legislation

|

STATE PARTICIPATION

In addition to the four mentioned

components, the O.P.R.L. Art. 6 (State Participation), affirms that the state

maintains the right to carry out or participate in petroleum activities.

Apparently, the state participation option will not be part of Lebanon's first

licensing round. So, presently, there is no state participation in the E.P.A.

at the time of award, but, the state or any entity owned by the state could in

the future become a right holder pursuant to additional assignment rules, and

early termination and forced assignment rules. At the time of this writing,

state participation has yet to be defined. And, until now, petroleum literature

has not been able to demonstrate that direct state participation provides some

additional benefits that could not be achieved from taxes — many a time states

decide to participate on the ground of non-economic considerations, e.g.,

control, technology transfer, national pride. For sure, for a state, state

participation augments administrative complexity and risk, while for the

investing I.O.C.s, it represents a cost and sometimes the implementation of

suboptimal decisions concerning the hydrocarbons development. So, for a country

as small as Lebanon, the benefits of establishing a national petroleum company

are not so evident.

Summing up Lebanon's proposed E.P.A.

should consist of four or five elements.

THE FISCAL TERMS

In light of the presence of a royalty,

some commentators see the Lebanese P.S.C. as a hybrid between a concession and

a P.S.C. This is an opinable point of view because most of modern P.S.C.s have

a royalty included. Moreover, governments have the objective of maximizing the

value of government revenues in their petroleum arrangements with I.O.C.s. and

they can reach this goal through whatever petroleum arrangement they decide to

sign: concession, P.S.C., and service contract.

The E.P.A. seems to primarily recall

the definitions set forth in the O.P.R.L. and the P.A.R. So, as defined in Art.1 of the O.P.R.L., the E.P.A. is "[a]n agreement concluded between the State and no less than three Right Holders". A right holder can be a

single company or a group of companies in which at least one meets the

prequalification eligibility criteria set forth in the Pre-Qualification

Decree. One of them is the operator (with at least a 35 percent participating

interest, while non-operators have a minimum 10 percent participating

interest), responsible for carrying out day-to-day activities, although all

right holders are jointly and severally liable for their obligations. The idea of an unincorporated joint venture (U.J.V.) is quite common in petroleum ventures, while it's unusual in the mining sector where major companies own

majority stakes in locally incorporated vehicles. U.J.V.s serve the interest of

both governments (more involved actors) and I.O.C.s (more flexibility).

According to the information concerning

the E.P.A. posted online by the L.P.A., right holders may explore for petroleum

during a five-year exploration phase, which is divided into two periods

respectively of three years and two years. This exploration phase may be

extended up to 10 years with the approval of the council of ministries. This

timeframe, apart from the distinction of the five-year exploration phase into

two periods, is in line with the text of the O.P.R.L. where:

- Art. 12: Awarding Rights 2/a determines "an Exploration Phase not exceeding ten years".

- Art. 21: Extension of the Duration of an Exploration and Production Agreement determines that "If the Exploration phase, provided by the Exploration and Production Agreement is shorter than ten years, the Council of Ministers may, upon an application submitted to the Minister, and on the basis of a proposal by the Minister based upon the opinion of the Petroleum Authority, extend the Exploration phase within the ten year time limit".

With reference to the percentages for

acreage relinquishment, the legislation envisaged for Lebanon follows current

practices with P.S.C.s — see, for instance, in the Kurdistan Regional Government (K.R.G.) where P.S.C.s. call for the same percentages although with a partially different time frame: an initial period of five years (divided into

two sub periods of three years and two years like in Lebanon) extendable for

two additional years up to a total of seven years. In fact, in Lebanon, at the

end of the first period, right holders will relinquish 25 percent of the block,

and, if later there is an extension to the exploration phase, they will add an

additional 25 percent relinquishment (at that point relinquishment will amount

to 50 percent).

According to the L.P.A., for natural

gas there will be a royalty with a flat rate at 4 percent — instead, with

reference to oil, Lebanon wants to implement a flexible royalty rate between 5

percent and 12 percent in relation to a sliding scale linked to daily oil

production. Some analysts deem the royalty rate for gas as too low, while

others would like to avoid completely the royalty, which of course is a

regressive instrument. Indeed, these are two opposite points of view. But the

reality is that they both probably misread the overall structure of a petroleum

contract — in this case a gas contract. The slide above provided a detailed

explanation of what a royalty is today, but some additional notes concerning

Lebanon may help. A royalty is surely regressive (regressivity is intrinsic to

the concept of royalty no matter how we may formulate it), but it serves the

purpose of a government that wants to obtain a cash flow soon — and Lebanon

needs to obtain some profits quite early. At the same time, because this

royalty is not very high (it's true that it's a natural gas royalty and not an

oil royalty, which is always higher) so it's not an excessive fiscal burden for

the I.O.C.s that want to invest in Lebanon. But, as usual, when drafting a

petroleum contract every single element has to be aligned with all of the others.

A perfect royalty rate does not exist, and analysts should evaluate a royalty

rate in relation to the other parameters present in the contract. What matters

is the final result.

The L.P.A. says that "a percentage (determined by bidding) of the oil and gas is allocated to the Right Holders to reimburse their costs". Also this element is the kernel of a P.S.C. After

paying the royalty, the next application of the production is given to the

contractor in order to recover its costs. Usually, there is an upper limit

(a.k.a. ceiling), let's say for instance 40 percent of production, which may be

used every year for cost recovery. At least, the contractor's costs include all

capital costs (CAPEX) and the annual operating costs (OPEX) — let's put aside

other elements as interest on debt (not always allowed) and investment credit.

Without an upper limit I.O.C.s could quickly recover their costs and have a

reduced payback period, but, at the same time, this would run counter the

interest of the hosting government, which would see its initial revenues

postponed to a later time. A cost recovery limit is less regressive than a

royalty.

In Lebanon, every quarter, profit

petroleum, i.e., the production not otherwise allocated to cost petroleum

and/or royalty, will be evaluated on a biddable sliding scale that is related

to profitability (an R-factor for the immediately preceding quarter).

Investors like a sliding-scale

profit-petroleum split indexed on an R-factor, and they would probably like it

more if this was indexed on the rate of return of the investment because it

could accommodate concepts like the time value of money. An R-factor permits

investors to reduce the risk of the project thanks to the introduction of

flexibility in the fiscal structure of the contract. In Lebanon, the R-factor

is calculated in accordance to the formula:

Cumulative Cash Inflow / Cumulative

CAPEX

In any quarter, cumulative cash inflow

corresponds to:

Profit Petroleum + Cost Petroleum -

Operating Expenses

The following table shows the

percentages of profit petroleum implemented in relation to the R-factor.

LEBANON'S

R-FACTOR

|

||

R-Factor

|

Government's Profit Petroleum

Percentage

|

Right Holders' Profit Petroleum

Percentage

|

< than or = to 1

|

A%

|

100% - A%

|

> than 1 and < than RB

|

See the formula below

|

100% - % determined in the formula

below

|

= to or > than RB

|

B%

|

100% - B%

|

From the table above it emerges that

when the R-factor is greater than 1 and less than RB, the percentage of profit

petroleum pertaining to the state will be calculated according to the following

formula:

Government's Profit Petroleum

Percentage = A + [(B - A) . (R - 1) / (RB - 1)]

It is unusual to see the minimum profit sharing biddable especially since it can lead to a wide range of minimum government takes, thereby increasing the administrative burden and complicating revenue forecasting. Lebanon can improve its system by fixing the lower band of its share of profit petroleum and allowing companies to bid for two more upper tiers. The advantage of this approach is that it ensures a minimum government share of profit petroleum, rather than solely relying on the bidding process.

Yes, a biddable minimum profit-sharing

percentage means that for every signed E.P.A. there could be a different

minimum profit-sharing percentage. Administratively speaking, especially for a

country new to the petroleum business this could create a real mess. Instead,

an already decided minimum percentage could give more stability to the

country's revenues.

The future E.P.A. has necessarily to

clarify the rate of the Corporate Income Tax (C.I.T.). The L.P.A. in a

simplistic manner affirms that right holders must pay all the Lebanese taxes.

It's possible that Lebanon will use also the general income tax, which has a 15

percent rate, but until now it is not clear what the L.P.A. and the Ministry of

Finance will decide. Again, administratively speaking, it's easier for a

country to manage a single general C.I.T. for all the business sectors than to

manage the general C.I.T. together with a specific petroleum C.I.T. If the

C.I.T. is fixed, corporate taxes are relatively regressive, i.e., their burden

stays the same notwithstanding different rates of profitability.

So, in Lebanon, two out of four of the

P.S.C. main components, are biddable, i.e., the cost recovery limit and the

profit sharing. Lebanon has decided to have also a biddable work program. Work

program bidding is primarily used for affecting the quality and level of

exploration in an area. It's a means in order to control that the I.O.C.s work

on time and with good quality results. Of course, excessive working commitments

on the shoulders of the I.O.C.s risk increasing excessively the extraction cost

of every single unit. It's also not advisable that companies propose grandiose

working programs, not related to an efficient exploration, because, in doing

so, they will add relevant costs to the project in the end reducing the

quantity of available profit petroleum. In general, after a while, an excessive

working commitment forces the parties to the contract to a renegotiation.

SOME FINAL REMARKS

If Lebanon desires to move on with its

offshore gas potential it has to approve quite soon the two decrees. In

specific, the decree related to Lebanon's E.P.A. is of paramount importance for

the interested I.O.C.s in order to understand whether it may make sense for

them to invest in Lebanon. The L.P.A. has provided some elements concerning the

P.S.C.s that it has decided to implement; at a preliminary analysis Lebanon

future P.S.C.s seem very in line with today's standard P.S.C.s. implemented

across the world.

At the same time, it is difficult to

have a complete evaluation of the proposed E.P.A. because some elements need to

be clarified. Moreover, only the auction will permit a complete assessment; in

fact, the auction will tell Lebanon how the I.O.C.s intend to invest in

relation to the biddable elements (cost recovery limit, the profit sharing and

work program). When analyzing a P.S.C., in reality, it's the overall fiscal

package that matters for both the government and the I.O.C.s. If one parameter

is excellent, but then the whole picture is blurred, it's not helpful.

Especially during the current difficult

petroleum markets, Lebanon has to propose a fiscal framework with progressive

elements capable of balancing the interest of the government on the one side,

and the interest of the I.O.C.s on the other. Some companies are currently

investing in both Israel and Cyprus, and it's probable that, without the war in

Syria, some other companies (probably Russian) would be investing in Syria's

waters. This indicates that all of these countries, Lebanon included, have a

good hydrocarbons potential. There is really no need for none of these

countries to start a 'race to the bottom' in order to increase its

attractiveness for the energy companies.

But, at this point, after all of the

activities performed in the previous years, if the Lebanese government is

serious about developing an offshore natural gas industry, it has to pass the

two decrees and to give the green light to possible investors. If, on the basis

of purely economic considerations — for instance among them: excessive

extraction costs, the impossibility of exporting the natural gas unused

locally, the present turmoil in the petroleum sector, the scarce interest from

the side of the I.O.C.s, or even the preference for developing Lebanon's

onshore petroleum sector — the government does not want to develop the sector,

or if it wants to postpone the offshore project, it has to state its decision in a

clear manner. The current limbo, mixing hope and scant determination, is of no

avail for the overall development of Lebanon's economy.

APPENDIX

Lebanon's delimitation of its E.E.Z. is

a classic example of a messy procedure that in the end has permitted Israel to

try to move north its sea border with Lebanon.

Initially, in 2007, Lebanon established

the delimitation of its E.E.Z. with Cyprus along six equidistant points from

north to south with the possibility of additionally extending Lebanon's borders north and

south. Later, the Parliament did not ratify this agreement, and in 2009 the

council of ministers adopted a more precise second delineation, whose new

extended geographic coordinates (with extended north and south limits in order

to have triple-point borders — with Cyprus and Syria in the north and with

Cyprus and Israel in the south) were passed to the United Nations in July and October

2010. Lebanon's new delineation was based on the legal recommendation of

Unclos.

It's not difficult to understand why

Lebanon did not immediately state the final dimensions of its E.E.Z.: The

difficult relations among the involved countries are certainly the primary reason. But, bilateral negotiations are not the best way to trace borders involving

more than two countries.

In fact, when in December 2010 Cyprus and Israel agreed on the

their borders, they did not consider the mechanism for extending north and

south Lebanon's E.E.Z. according to the bilateral agreement between Cyprus and

Lebanon of 2007. Later Israel sent the coordinates of its E.E.Z. to the U.N. despite

the overlapping of 874 square kilometers with Lebanon's E.E.Z. In sum, this is the essence of the

problem between Israel and Lebanon in relation to their overlapping E.E.Z.s.

A final consideration, if, on the one

side, Lebanon could have probably acted in a more consistent way in order to state the borders of its E.E.Z., on the other hand, it's also true that Israel's

claims are, legally speaking, not particularly well substantiated.

For More Information Please See: