March 29, 2015

BEIRUT,

Lebanon

ABSTRACT

This

essay is the direct consequence of a request for advice that I have recently received

from a European broker who wanted to better understand the structure of the upstream oil

industry of the Kurdistan Regional Government (K.R.G.). After an initial

preamble recounting the difficulties that the broker experienced, the paper

applies the five forces analysis to the K.R.G. upstream oil sector. The five forces

analysis, developed by Professor Michael Porter of Harvard University, is one

of the most powerful business frameworks in order to understand the structure

of whatever industrial sector, upstream oil sector included. This essay is

strongly indebted to the book "Understanding Michael Porter" by Joan Magretta and the paper "The Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy" by Michael Porter.

PREAMBLE

Approximately

a month ago, a European commodities broker wanted my advice in relation to a

possible deal that he was negotiating with reference to oil from the Kurdistan

Regional Government (K.R.G.). In an initial phase, this broker and his team had

negotiated with some local Kurdish intermediaries in order to have a meeting at

the K.R.G. Ministry of Natural Resources (M.N.R.), but later they were not very

satisfied with the result. In fact, when they had gone to Erbil they had discovered

that they did not have any direct access to the M.N.R. and that those people they

were dealing with were probably simple wheeler-dealers offering crude oil with

a paltry discount — just around $2, with a commission fee of $1; at the

beginning the talks had revolved around a possible discount of $8 to $10 with

reference to Dubai Crude (A.P.I. gravity of 31 degrees and 2 percent sulfur content). So, the negotiations were interrupted. Later, when I was contacted, the

broker told me that he was negotiating a medium light from Khurmala (with

A.P.I. gravity of 34 degrees) with a $5 to $6 discount and a free on board (F.O.B.) delivery

at Ceyhan, Turkey. In specific, he was looking for 2 million barrels of crude

oil every month. With no doubt an important quantity. Also these negotiations

did not end well because the Kurds after a while replied that at least for the

coming six months they would not have any available free quantity of crude oil

to sell.

This

reply could make sense in light of the current difficult implementation of the

December 2014 oil deal between Erbil and Baghdad. This agreement established

that the K.R.G. should export 250,000 barrels per day of

its own oil and 300,000 barrels per day from the Kirkuk fields that the K.R.G. currently

controls — 550,000 bbl/d in total (for more information please see: BACCI, A., The Iraqi-Kurdish Oil Deal, December 2014). But, already last December when it was

discussed, the deal appeared very shaky; and since then both sides have

presented different numbers in relation to the oil currently exported by the

K.R.G.; indeed, as a consequence of this confusion, it's not easy to find an acceptable compromise. The federal

government affirms that the K.R.G. is presently delivering only 135,000 bbl/d

to Iraq's central State Organization for Marketing Oil (SOMO), while Erbil

responds that it is delivering approximately 400,000 bbl/d, which is the

highest production it can reach at the moment. Kurdish sources affirm that by

the end of April the K.R.G. will be able to export 625,000 bbl/d. At the same

time, the

Iraqi federal government has not been able to hold up its side of the deal. In

fact, Baghdad sent to Erbil a first payment of around US$200

million at the beginning of March and then around mid-March a $420million budget payment. The problem is that it is still short of its December

2014 commitments. In any case, in light of the relevant quantity requested, I

immediately suggested that the broker and his team have contact only and

exclusively with the Ministry of Natural Resources. The daily production of

Iraqi Kurdistan is currently 400,000 bbl/d, i.e., around 12 million bbl/m, so a

monthly request of two million barrels means one-sixth of the overall Kurdish

production in a month. Moreover, in order to have some additional information

on the part of the international oil companies (I.O.C.s) working in Iraqi

Kurdistan, I contacted Genel Energy, an Anglo-Turkish company, which is the

most important producer of crude oil in the K.R.G — it is the lead foreign

partner in the development of the Taq Taq field (A.P.I. gravity of 48 degrees) whose

production capacity is 130,000 bbl/d according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (E.I.A., January 2015). Head of Public Relations, Andrew Benbow,

rightly confirmed me by e-mail that as

Genel Energy passed on its oil at the wellhead and the K.R.G. was the exporter,

it was the K.R.G. that a buyer needed to contact.

THE IDEA BEHIND THIS ANALYSIS

The

basic idea of this analysis is to define the industry structure of the K.R.G.

oil sector according to Michael Porter's five forces framework. As Professor

Porter points out "the real point of competition is not to beat your

rivals. It's to earn profits." And, according to the story I have

presented in the previous paragraphs, it has clearly emerged that an evaluation of the K.R.G. oil sector could be very helpful in order to understand how to work in Iraqi Kurdistan.

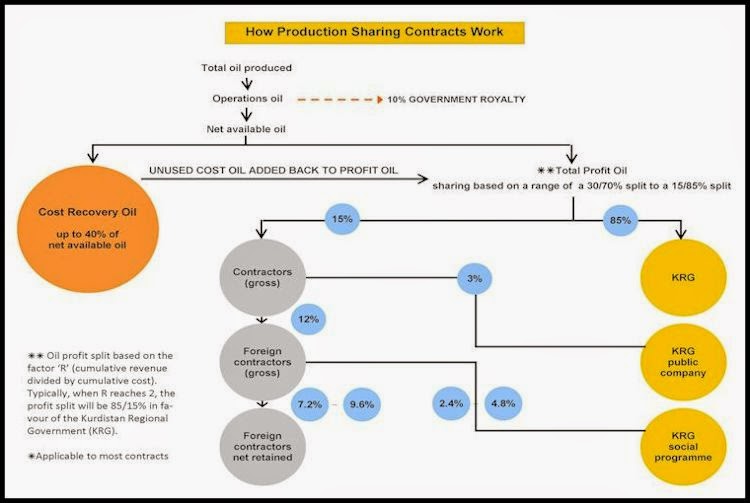

The perspective of this analysis is centered on the couple I.O.C.s/K.R.G., which is to be considered as the "oil-producing entity". In Iraqi Kurdistan, I.O.C.s and the K.R.G. are linked through a production sharing contract (P.S.C.). Under a P.S.C. the contractor makes risk investments and provides technical and management services in return for a share of production to recover its costs (“Cost Oil”) and a share of the remaining oil (“Profit Oil”) as its profit. The contractor has the right to market its share of oil and "book" the reserves. In the production phase, however, the government of the hosting country may take a direct stake in the project. In general, the extent of the government's participation varies from less than 30 percent to as much as 70 percent. As a consequence, the government shares "rewards and technical, price, and operating cost risks with the I.O.C. in proportion to itsshare in the project" (Maurer - Tarontsi, 2009). In addition, the government collects taxes and royalty payments.

|

| Elements of Industry Structure — Source: Wikipedia |

The perspective of this analysis is centered on the couple I.O.C.s/K.R.G., which is to be considered as the "oil-producing entity". In Iraqi Kurdistan, I.O.C.s and the K.R.G. are linked through a production sharing contract (P.S.C.). Under a P.S.C. the contractor makes risk investments and provides technical and management services in return for a share of production to recover its costs (“Cost Oil”) and a share of the remaining oil (“Profit Oil”) as its profit. The contractor has the right to market its share of oil and "book" the reserves. In the production phase, however, the government of the hosting country may take a direct stake in the project. In general, the extent of the government's participation varies from less than 30 percent to as much as 70 percent. As a consequence, the government shares "rewards and technical, price, and operating cost risks with the I.O.C. in proportion to itsshare in the project" (Maurer - Tarontsi, 2009). In addition, the government collects taxes and royalty payments.

According

to Paragraph 1 under the title "Government Interest" of Article 4 —

Options of Government Participation and Third Party Participation of the Production Sharing Contract Model of the K.R.G.:

The GOVERNMENT shall have the option of participating through a Public Company in this Contract, in respect of the entire Contract Area, as a CONTRACTOR Entity, with an undivided interest in the Petroleum Operations and all the other rights, duties, obligations and liabilities of the CONTRACTOR (save as provided in and subject to this Article 4) under this Contract in respect of the Contract Area, of up to [ ] per cent ([ ]%), and not less than five per cent (5%) (the “Government Interest”), such option being referred to herein as the “Option of Government Participation”. The GOVERNMENT shall be entitled to exercise the Option of Government Participation by notifying the CONTRACTOR in writing of such election and the size of the Government Interest.

So, according to these considerations,

it makes sense to analyze the industry structure of the K.R.G. through the

perspective of the oil-producing couple I.O.C.s/K.R.G.

The International Energy Agency (I.E.A.) in its Iraq Energy Outlook of November 2012 estimated that Iraqi Kurdistan contained 4 billion barrels of proved

reserves. Instead, the K.R.G. estimates are much higher because they include

unproved resources too. Quite recently the K.R.G. has increased its oil

resources estimate from 45 billion barrels to 60 billion barrels — some

resources are in the areas disputed between Erbil and Baghdad.

|

| The Kurdistan Region — Source: Petroleum Economist |

|

| The Kurdistan Region — Source: Petroleum Economist |

On average, in Iraq proper it costs about $5 to produce a barrel of oil; with reference to the K.R.G., we are in the same range. For instance, Genel Energy, one of the operators in Iraqi Kurdistan, has finding and development costs (F&D) less than $3 a barrel and operating expenses (OPEX) less than $2. Tony Hayward of Genel Energy has recently declared that his company could still profitably produce a barrel of oil with oil prices around $20 a barrel. In times of low oil prices, low production costs are a huge advantage for oil-producing countries and the companies technically doing the job. For more information please see: BACCI, A., Why Do I.O.C.s Have to Invest in Iraqi Kurdistan and/or Southern Iraq?, December 2014.

In other words, notwithstanding

the current complex and harsh dispute between Erbil and Baghdad, the

combination of relevant oil reserves and the low production costs has been a

powerful tool capable of attracting to Iraqi Kurdistan in the last years around

fifty international oil companies — initially small and medium companies and

later large ones. Addax Petroleum — at that time a Swiss company, while today

it's a subsidiary of China's Sinopec — and Genel Energy together signed a

P.S.C. related to the Taq Taq field as early as May 2004. Today, also four big

names are investing in Iraqi Kurdistan: U.S. ExxonMobil and Chevron, France's

Total and Russia's Gazprom. For more information please see: BACCI, A., Chevron and Total Continue Investing in the K.R.G. A Brief Analysis of Baghdad's T.S.C.s vs. Erbil's P.S.C.s, June 2013.

Four are the most important oil

fields in the K.R.G.:*

1) Khurmala Dome (Iraqi

Kurdistan's KAR Group, 110,000 bbl/d, A.P.I. gravity of 34 to

25 degrees),

2) Tawke (Norway's D.N.O. and

Genel Energy, 130,000 bbl/d, A.P.I. gravity of 26 to 28

degrees),

3) Taq Taq (Genel Energy and

Sinopec, 130,000 bbl/d, A.P.I. gravity of 47 to 48 degrees) and

4) Shaikan (Gulf Keystone,

21,000 bbl/d, A.P.I. gravity of 18 degrees).

*(Data relative to January 2015)

At the end of January 2015 the

K.R.G. production capacity stood at approximately 400,000 bbl/d, of which

150,000 bbl/d were sold and refined locally within the K.R.G. thanks to the

Kalak refinery, near the capital Erbil, and the Bazian refinery, in Sulaymania Governorate.

|

| Source:

The Energy Information Administration (January 2015) |

This analysis covers the industry structure of the oil sector in the K.R.G. alone; the fields around the city of Kirkuk are not considered. In fact, notwithstanding that the K.R.G. expanded its control over the Kirkuk area in June 2014, it's not clear what the political future of the city and its governorate will be. The Peshmerga forces blocked the possibility that the city and its precious oil reserves fell into the hands of the Islamic State, but already today, one of the most contentious issues between the federal government and the K.R.G. is the destiny of Kirkuk and its oil riches. In fact, the Kurds strongly insist that the oil-rich city of Kirkuk and the surrounding areas be included in the K.R.G. For more information please see: BACCI, A., Iraqi Kurdistan's Occupation of Kirkuk Oil Field Will Deeply Affect the Iraqi Oil Sector, June 2014.

THE INDUSTRY STRUCTURE OF THE K.R.G. OIL SECTOR

Joan

Magretta of the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness at Harvard Business School correctly explains that "competition is the tug-of-war over profits

that occurs not just between rivals but also between a company and its

customers, its suppliers, makers of substitutes, and potential new

entrants." In other words, it's meaningless to compete in order to be the

best for the simple reason that there are many ways to serve customers, who

indeed may have very different necessities. In sports it may make sense to

speak about "competing in order to be the best"; unquestionably on

February 1, 2015, the New England Patriots won the XLIX Super Bowl defeating

the Seahawks 28-24. But, in the business arena "competition is more complex,

more open ended and multidimensional. Within an industry, there can be multiple

contests, not just one, based on which customers and needs are to be

served." So the real competition relates to competing for

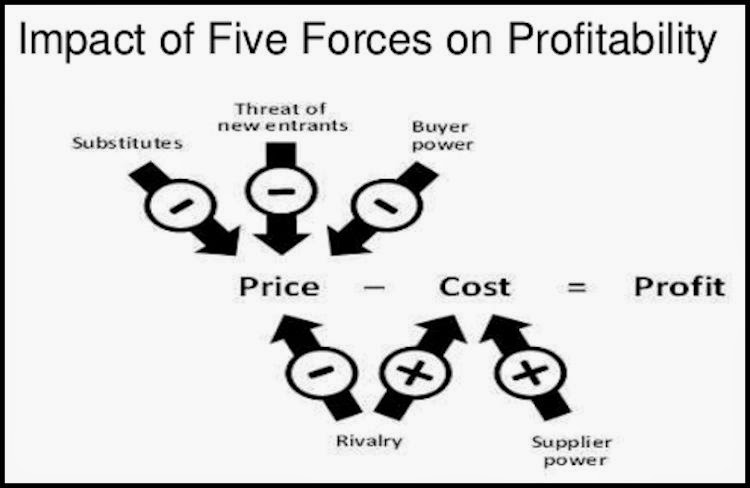

"profits", which derive from the following equation:

PROFITS

= PRICE - COST

And

this concept is absolutely true in relation to every single P.S.C. that the

K.R.G. has signed in the last years with an I.O.C. Both, the government and the

I.O.C., work with the goal of doing profits not with the goal of being the

best.

So

the industry structure determines profitability. One of the most complete

frameworks in order to assess competition in any industry is the analysis of the

industry's structure according to Porter's five forces.

|

| Source: "Understanding Michael Porter" by Joan Magretta |

|

| Source:

"Understanding Michael Porter" by Joan Magretta |

|

| Porter’s Five Forces Model of Competition — Source: MAX 360 @AIGROUP |

The Threat of New Entrants (Low)

"The

threat of entry in an industry depends on the height of the entry barriers that

are present and on the reaction entrants can expect from incumbents"

(Porter 1998).

In

relation to the oil sector, and this is completely applicable to the K.R.G.

upstream oil sector, these are today's main entry barriers:

1)

Supply-side economies of scale

If

an oil contract equitably balances the interests of the involved I.O.C.s and

the host country, oil firms producing at larger volumes normally enjoy lower

costs per unit because they are able to spread their fixed costs over more

units (barrels), they employ more efficient technology or negotiate better

terms with equipment suppliers and/or subcontractors. In fact, CAPEX are

practically the same if from a reservoir we extract 100 bbl/d or 100,000 bbl/d,

but, of course, the more barrels we extract the lower it is their marginal

cost. The Kurdish P.S.C.s well align the interests of the investors and the government; both want to find large and low costs oil fields (van Meurs, 2008). In this regard,

it should be noted that in the oil business many a time there are contracts (quite

often with Service Contracts) where there is no real incentive for the

investors to find large low cost fields.

2)

Capital requirements

The

oil sector is a capital intensive business. A company starts spending important

economic resources immediately after the signature of an oil contract — no

matter what type of contract it has signed. And new oil projects have long time

horizons before permitting to recoup some of the investments. So, in light of

their reduced cash availability, small companies (the so-called wildcatters)

and midsized companies need to have a short timeframe between the exploration

phase and the production phase. If these companies do not get stable and continual

payments, they risk a bankruptcy. Current developments in the K.R.G. show that

the three midsized companies that are already producing crude oil, Genel

Energy, D.N.O. and Gulf Keystone are all experiencing economic troubles because

they have not received stable and continual payments from the K.R.G.; only Genel

Energy has a better financial position because last year it did a bond issue

through which it raised $500 million, and because in addition to it, the company has recently

completed the private placing of $230 million of bonds.

3)

Restrictive government policy

As

a consequence of the nationalizations of the 1970s in the Middle East the oil

sector has a widely restricted access — still today Saudi Arabia's oil sector

is completely sealed off for foreign companies (although not the non-associated

gas sector). Oil belongs to the host country and, in general, if an I.O.C.

wants to sign a deal, it has to participate in a bidding process or to

negotiate directly with the host country, which will decide all the contractual

terms. In a country there could be parts of territory where there are proven,

probable or possible reserves, but without a contract there will be no access

to them. In the K.R.G. any company interested in developing an oil field needs

to sign a very detailed P.S.C. with the regional government. Erbil has

developed a production sharing contract model, and every signed contract is

based on this model. The decision of using P.S.C.s has been strongly criticized

and opposed by the federal government, which has always favored technical

service contracts (T.S.C.), which it signs after an auction.

"Powerful suppliers capture more

of the value for themselves by charging higher prices, limiting quality or

services, or shifting costs to industry participants. Powerful suppliers,

including suppliers of labor, can squeeze profitability out of an industry that

is unable to pass on cost increases in its own prices" (Porter, 1998).

The K.R.G. oil sector with reference to the power of

suppliers follows the general trend present in the oil and gas industry: a

balanced relation between suppliers and oil companies. In fact, it's true that

many international oil companies are vertically integrated, but it is also true

that, with reference to the specific tasks they have to implement, they utilize

many different subcontractors. And, in general, there is a sort of one-to-one relation

between suppliers and oil companies: The latter need the specific skills of the

former, but, at the same time, the suppliers depend heavily on the oil industry

for their revenues because they are not able to serve different industries. There

is no doubt that industry participants face switching costs in

changing suppliers, that suppliers offer products that are differentiated and

that there is no substitute for what the supplier group provides, but, in light

of the high specialization (tailor-made services) of the provided services, the

suppliers do not have many alternative buyers. Only in recent years, the power

of suppliers has partially augmented because some supplier groups have

succeeded in integrate forward into the industry so that they have managed

projects previously operated exclusively by an I.O.C.

The Power of Buyers (Final Buyers Low — Direct Buyers Medium)

"Powerful customers—the flip side of powerful

suppliers—can capture more value by forcing down prices, demanding better

quality or more service (thereby driving up costs), and generally playing

industry participants off against one another, all at the expense of industry

profitability. Buyers are powerful if they have negotiating leverage relative

to industry participants, especially if they are price sensitive, using their

clout primarily to pressure price reductions" (Porter 1998).

In the oil business, market demand is a primary

factor in setting prices, but it is important to differentiate between the

buyers of crude oil in the physical market and buyers of refined

products (for instance, gasoline). In fact, the individual purchaser of refined

products, who is also the final consumer of the transformed crude oil, is an individual with low

bargaining powers. For instance, if a driver needs to use his car, he will

always pay the price per gallon as indicated on the billboard at the gas

station. He will complain that prices are high, but he will not have any

tangible power to lower them.

Instead, when analyzing the structure of the oil

industry in a specific area (be it a country, a region or a province) it is

probable more useful to focus our attention on the direct buyers, who are

most often refiners who process the crude oil into the various petroleum

products for commercial and retail customers, or international traders. Most

refining capacity in the world is owned and operated by the larger integrated

companies, the N.O.C.s and, recently also by independent refining sector

companies.

Direct buyers have a relevant negotiating power

because:

1) They are not many and because they purchase in

volume that are large relative to the size of the vendor.

2) The industry's products are standardized or

undifferentiated. Many a time crude oil exports from a specific country are a

single blend of all the crude types present in that country. In general,

refineries are not able to process all the types of blend present on the

market, but still on the market they can purchase alternative blends satisfying

the requirements of their processing plants.

3) Buyers face few switching costs in changing

vendors. Although there are different blends, oil is a commodity.

With reference to the K.R.G. there are two different

types of direct buyers: Turkey's refiners (for instance, Tüpraş), and

international traders and refiners (these may be integrated in an oil company

or independent too).

It is important to focus our

attention on Turkey because this country is not only a significant oil

consumer in its own right, but it is also a natural energy hub between three

major oil-producing areas (Russia, the Caspian Sea basin and the Middle East)

and the European consumer markets. Moreover, Ceyhan is a port that is able to

accommodate very large crude carriers (V.L.C.C.) and ultra large crude carriers

(U.L.C.C.).

According

to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (E.I.A.):

In 2013, Turkey's total liquid fuels consumption averaged 734,800 bbl/d. More than 90% of crude oil consumption and significant quantities of petroleum products came from imports. According to the IEA [International Energy Agency], Turkey's crude oil imports are expected to double over the next decade. In 2012, the majority of Turkey's crude oil imports came from Iran, which supplied 35% of the country's crude oil. Russia, once the largest source country of Turkey's crude oil, has fallen behind Middle East suppliers in terms of volume and is now the fourth-largest supplier of crude oil to Turkey.

There

is a strong economic complementarity between Iraqi Kurdistan and Turkey. The

latter needs the K.R.G. crude oil (and gas too), while Iraqi Kurdistan needs

the revenues obtained from selling oil to Turkey. In practice, an oil trade

between the K.R.G. and Turkey is a win-win solution for both sides — although for

the K.R.G. it would not be advisable to have an important dependence on a

single buyer. For more information please see: BACCI, A., Why Do I.O.C.s Have to Invest in Iraqi Kurdistan and/or Southern Iraq? February 2015.

After

years of flat markets, falling profits and declining margins, international oil

traders (for instance, Glencore, Gunvor, Mercuria, Trafigura and Vitol) are

currently experiencing very favorable conditions since the global financial

crisis of 2008. The rise in oil volatility is helping the traders to obtain

improved margins in their transactions —more arbitrage. The current slide in crude oil since mid-June 2104 has also provided an important boost to the profit margins for the ailing European refining industry, which struggled to turn a profit when crude oil remained at or around $100 a barrel.

It

is worth remembering that international refiners and traders are price

sensitive because:

1)

The oil they buy represents a significant fraction of their cost structure or

procurement budget.

2)

In general they have low margins and/or are under pressure to trim their purchasing

costs.

3)

The quality of services they provide is little affected by the industry's product.

4)

Crude oil has little effect on the buyer's other costs.

All

these elements, which are completely valid also for the refiners and traders

working with the K.R.G. oil, explain that oil refiners and oil traders have a certain

negotiating leverage relative to the K.R.G. This is exactly what happened with

the broker who contacted me. He was not satisfied with the terms obtained from

the K.R.G. and he walked away without a deal because he knew that he might find

some alternatives: Iraqi Kurdistan exports a blended medium (crude oil quality of 30 to

32 degrees A.P.I. and 2.52 percent sulfur content) that is very similar to the Kuwaiti

blended medium (crude oil quality of 31.4 degrees A.P.I. and 2.52 percent

sulfur content).

In

addition, low international oil prices (Brent, the widely used international reference, is at $57 per barrel when

last June it was around $115) and the strong confrontation between Erbil and

Baghdad with reference to the exports of Kurdish oil from the K.R.G. (a high

political risk) are two elements (two external factors, not two forces) that

reduce the power of the oil producers versus the buyers. An oversupply of crude

oil reduces the prices that the K.R.G. may ask for and at the same time if the

buyer may experience a possible lawsuit after purchasing crude oil from the

K.R.G., he will necessarily request an important discount — we apply the same

logic of the bond market: a higher risk requires a higher reward; the only

different is that with bonds there is a higher interest rate and with

quantities of crude oil an initial discount.

The Threat of Substitutes (Low)

"A substitute performs the same or a similar

function as an industry’s product by a different means" (Porter 2008).

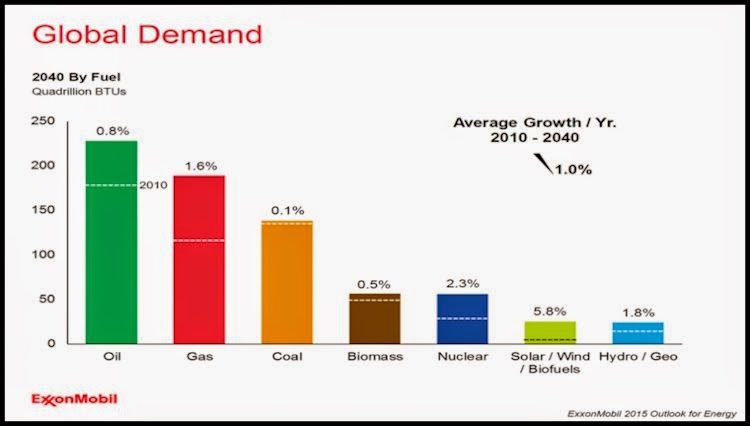

Oil is primarily used as a

transportation fuel. According to ExxonMobil "oil is expected to remain the No. 1 energy source and demand will increase by nearly 30 percent, driven by expanding needs for transportation and chemicals". In other words, it is difficult to imagine a real alternative

(from renewable energy sources, nuclear power or other fossil fuels) to oil in

the transportation business in the coming years. Moreover, there will be an

overall increase in the consumption of crude oil in the transportation sector

in the coming decades.

"Rivalry among existing competitors takes many

familiar forms, including price discounting, new product introductions,

advertising campaigns, and service improvements. High rivalry limits the

profitability of an industry. The degree to which rivalry drives down an

industry’s profit potential depends, first, on the intensity with which companies compete

and, second, on the basis

on which they compete"

(Porter 2008).

Rivalry

in the upstream oil business is quite high for the following considerations:

1)

There are many competitors.

2)

Industry growth is slow.

3)

Exit barriers are very high.

4)

Rivals are highly committed to the business and have aspirations for leadership.

5)

The involved actors have a different approach to competing.

In

general, "rivalry is especially destructive to profitability if it

gravitates solely to price because price competition transfer profits directly

from an industry to its customers" (Porter 2008). This occurs when:

1)

Products or services of rivals are nearly identical and there are few switching

costs for buyers.

2)

Fixed costs are high and marginal costs are low.

3)

Capacity must be expanded in large increments to be efficient — with possible

oversupply.

4)

The product is perishable (this does not happen with crude oil)

Apart

from the fourth point, which has no relation with crude oil, the three initial points

should be able to force a real price competition capable of transferring

profits to customers. This is exactly what has occurred in the last months when

consumers around the world have enjoyed reduced prices at the pump. Oil supply

and oil demand determine the price of oil, but many times some external

factors, like wars, sanctions and cartels, may contribute to cancel the

availability of some reserves from the world map. The result is that, notwithstanding

the high rivalry in the upstream oil sector among the involved players, it is

not automatic that profits are transferred to direct buyers and then to

consumers. Currently, this profits transfer is occurring because the increase

of the U.S. production of unconventional oil has permitted a considerable

reduction in the price of a barrel of oil.

The

I.O.C.s/K.R.G. entities working in Iraqi Kurdistan face an important rivalry at

the world level because it is there that they really compete — this is their

geographical scope. In fact, only a

reduced quantity of the Kurdish crude oil production, around a quarter, is sold

domestically in Iraqi Kurdistan with a price significantly cheaper than the

international market price. In specific, the various I.O.C.s/K.R.G. entities pass

on their crude oil at the wellhead and then Kurdish Oil Marketing Organization

(KOMO) or State Oil Marketing Organization (SOMO) of Iraq proper — the export

channel is an important friction point between Erbil and Baghdad — sells

approximately three-quarters of the Kurdish crude oil production (the lion's

share of the production) abroad, on the world markets, via the Kirkuk-Ceyhan

pipeline. The Kurds have built two pipelines that enter the Kirkuk-Ceyhan

pipeline at Fishkhabur because the section from Kirkuk to Fishkhabur has been

out of service since March 2014 as a consequence of repeated militant attacks.

In fact, the Iraqi section of the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline runs through Islamic

State-controlled territory. So, Kurdish oil necessarily competes with the

production of several different countries, which may have crude oils with

characteristic very similar to the Kurdish one.